Small Island, Big Issue: Malta and its Search and Rescue Region - SAR

Paix et Sécurité Internationales – Journal of International Law and International Relations, no. 7, pp. 299-321, 2019

Universidad de Cádiz

Notas

Abstract: Malta is located at the frontline of the Central Mediterranean route. It is a waypoint for migrants coming from the North African coast and crossing the Mediterranean, who have to pass through the Maltese search and rescue region. Malta acceded to the 1979 SAR Convention in 2002, but it has not yet signed the 2004 Amendments which clarify that the disembarkation of persons found in distress at sea must be done in a place of safety.

Resumen: Malta se encuentra en la primera línea de la ruta del Mediterráneo central. Es un pun- to en el recorrido de los migrantes que vienen de la costa norteafricana y cruzan el Mediterráneo, que tienen que pasar por la zona de búsqueda y salvamento maltesa. Malta se adhirió al Convenio SAR de 1979 en 2002, pero aún no ha firmado las Enmiendas de 2004 que aclaran que el desembar- co de personas encontradas en peligro en el mar debe realizarse en lugar seguro.

Palabras clave: Convenio SAR, Zona SAR - Malta - búsqueda y salvamento marítimo - lugar seguro.

Résumé: Malte est située sur la ligne de front de la route méditerranée centrale. C’est un point de passage pour les migrants venant de la côte nord-africaine et traversant la Méditerranée, qui doivent parcourir la région maltaise de recherche et de sauvetage. Malte a adhéré à la Convention SAR de 1979 en 2002, mais n’a pas encore signé les Amendements de 2004 qui précisent que le débarque- ment des personnes trouvées en détresse en mer doit être réalisé en lieu sûr.

I. INTRODUCTION

Every year, hundreds of thousands of people endanger their lives in jour- neys across the Mediterranean Sea as a result of famine, armed conflicts, poverty, and many other causes. In the pursuit of better conditions of life, Malta is one of the main points of arrival.

Many of these migrants find themselves in distress during those long journeys. The duty to assist persons in distress at sea is a long-established rule of customary international law which was codified as a general and un- conditional obligation by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea2 (hereinafter, UNCLOS). Article 98 of UNCLOS states, with regards to flag States, that:

Every State shall require the master of a ship flying its flag, in so far as he can do so without serious danger to the ship, the crew or the passengers: (a) to render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost; (b) to proceed with all possible speed to the rescue of persons in distress, if informed of their need of assistance, in so far as such action may reasonably be expected of him.

Article 98(2) further provides that “all coastal States promote the establi- shment, operation and maintenance of an adequate and effective search and rescue service regarding safety on and over the sea and, where circumstances so require, by way of mutual regional arrangements cooperate with neigh- bouring States for this purpose.”

The duty to assist in distress as such is not geographically limited in any way.3 Irrespective of where a vessel encounters another vessel in distress, it is obliged to assist it. The duty to rescue is further clarified in a number of international maritime law instruments, namely, the Convention for the Safe- ty of Life at Sea,4 and the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (hereinafter, SAR Convention).5

Before the SAR Convention, there was no international system for stan- dardised search and rescue operations.6 The International Maritime Orga- nisation (hereinafter, IMO) highlights how the SAR Convention guarantees that “no matter where an accident occurs, the rescue of persons in distress at sea will be co-ordinated by a SAR organisation and, when necessary, by co-operation between neighbouring SAR organisations.”7 The declaration of a search and rescue region (hereinafter, SAR region) is a unilateral right of States contracting party to the SAR Convention. In accordance with the in- ternational rules, the interested State shall initiate a process to establish SAR bilateral agreements with its neighbours.

In this context, Malta, at the crossroads in the Mediterranean Sea, is res- ponsible for a vast area and must take primary responsibility for ensuring that assistance is provided within its SAR region to any person in distress, either individually or in co-operation with other States.8

II. SEARCH AND RESCUE REGIONS

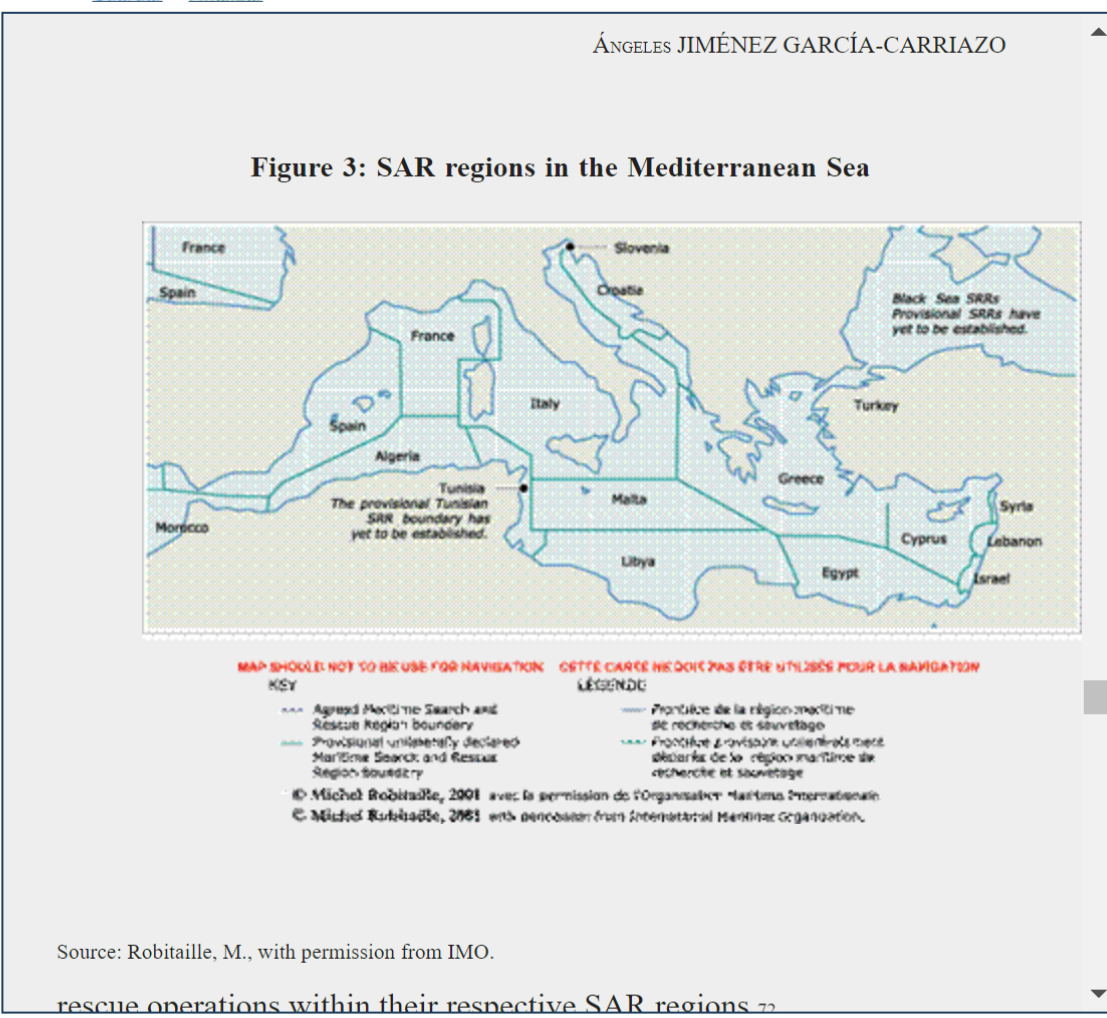

Following the adoption of the SAR Convention, IMO divided the world’s oceans into thirteen search and rescue areas, in each of which the relevant countries have a delimited SAR region for which they are responsible.9 Parties to the Convention are encouraged to enter into agreements with neighbou- ring States in order to delimit the SAR regions and arrange cooperation in search and rescue operations. These regions should be contiguous and, as

far as practicable, not overlap.10 SAR regions are notified to the IMO Secre- tary-General11 and are made available in the IMO Global Search and Rescue Plan.

The obligation of States to provide search and rescue services is princi- pally limited to their own SAR region.12 In this regard, the SAR Convention provides that “[o]n receiving information that any person is, or appears to be, in distress at sea, the responsible authorities of a Party shall take urgent steps to ensure that the necessary assistance is provided.”13

In order to effectuate this provision of service, States are directed to es- tablish national rescue co-ordination centres (hereinafter, RCCs), which shall arrange for the receipt of distress alerts originating from within its SAR re- gion.14 If a RCC receives information of a distress incident taking place be- yond its SAR region, it is obliged to take immediate action to assist and notify the responsible RCC in whose area the incident has occurred.15

In the case of Malta, its location in the southern Mediterranean places this island in an area which is conducive to the arrival of people who risk their lives aboard unseaworthy boats. Malta is located in the path of migration flows from North Africa (particularly, Libya) to Europe where it serves both as a destination and transit point16 along the Central Mediterranean route.17

In contrast to the small size of its territorial waters, Malta maintains a

vast SAR region, covering some 260,000 square kilometres.18 Its SAR region coincides with the Malta Flight Information Region, which the State inheri- ted from the British Flight Identification Region.19 The SAR region of Malta extends from Tunisia, to the west, to the Greek island of Crete, to the east. Toward the north, there is an overlap between Maltese and Italian SAR re- gions.

The Maritime Safety Committee of IMO20 at its 69th session adopted by resolution MSC.70(69),21 amendments to revise the Annex to the SAR Con- vention. The revised annex puts greater emphasis on the regional approach and co-ordination between maritime and aeronautical search and rescue operations. Subsequently, at the 78th session, the Maritime Safety Commit- tee adopted, by resolution MSC.155(78),22 new amendments to Chapter II (organization and co-ordination) relating to definition of persons in distress, Chapter III (co-operation between States) relating to assistance to the mas- ter in delivering persons rescued at sea to a place of safety, and Chapter IV (operating procedures) relating to rescue co-ordination centres initiating the process of identifying the most appropriate places for disembarking persons found in distress at sea.

The clarification of these obligations in the latter amendments responds

cued over 430 asylum seekers in the Indian Ocean and was refused entry to Australian waters.23

According to the latter revision, States Parties shall co-ordinate and co-operate to ensure that the masters of ships providing assistance by em- barking people in distress at sea are released from their obligations with mi- nimum further deviation from the ship’s intended voyage, as well as relevant measures are taken for the disembarkation to be effected as soon as reasona- bly practicable.24 The government in charge of the SAR region in which the survivors are recovered is held responsible for providing a place of safety on its own territory or ensuring that such a place of safety is granted.25

The SAR Convention provides as follows:26

Parties shall co-ordinate and co-operate to ensure that masters of ships pro- viding assistance by embarking persons in distress at sea are released from their obligations with minimum further deviation from the ships’ intended voyage, pro- vided that releasing the master of the ship from these obligations does not further endanger the safety of life at sea. The Party responsible for the search and rescue region in which such assistance is rendered shall exercise primary responsibility for ensuring such co-ordination and co-operation occurs, so that survivors assisted are disembarked from the assisting ship and delivered to a place of safety, taking into account the particular circumstances of the case and guidelines developed by the Organization. In these cases, the relevant Parties shall arrange for such disembarka- tion to be effected as soon as reasonably practicable.

Malta has formally objected the 2004 Amendments to the SAR Conven- tion. The Maltese authorities argued that the amendments required the State responsible for the SAR region within which persons are rescued to assume responsibility for providing the safe disembarkation place.27 On 22 December 2005, the depositary received the following communication from the Minis- try of Foreign Affairs of Malta:

[…] the Ministry wished to inform that, after careful consideration of the said amendments, in accordance with article III(2)(f) of this Convention, the Govern- ment of Malta, as a Contracting Party to the said Convention, declares that it is not yet in a position to accept these amendments.”28

Therefore, Malta is not bound by the amendments on the grounds that they could be interpreted as imposing on the State the obligation to disem- bark on its own territory and offer assistance to all those rescued within its SAR region.29

III. INTERPRETATION OF THE CONCEPT OF PLACE OF SAFETY

The concept of place of safety is undefined in SAR Convention. The Convention does not provide specific rules for interpretation and does not

identify which is the State, among a number of neighbouring States, which should provide assistance in a given case. The fact that the Government of the SAR region in which the survivors are recovered is responsible for pro- viding a place of safety, or ensuring that such a place of safety is provided, means that migrants in distress at sea are sometimes brought to the SAR region of another State.30

Some authors consider that the primary responsibility of the State res- ponsible for the SAR zone relates only to ensure co-ordination and co-ope- ration.31 However, the SAR Convention does not address how to solve the situation in the case that no agreement is reached, and avoids any reference which could imply the assumption that, in default of any specific agreement, people saved should be disembarked in the State responsible for the SAR region.32

In the absence of legal definition, and with the aim of guaranteeing that persons rescued at sea are provided a place of safety regardless of their natio- nality, status or the circumstances in which they are found, the Guidelines on the Treatment of Persons Rescued at Sea were adopted by IMO.33 Although the Guidelines do not establish any binding duty, they provide some guidan- ce on the interpretation of the obligations to render assistance at sea.34 The Guidelines define a place of safety as “a location where rescue operations are considered to terminate. It is also a place where the survivors’ safety of life is no longer threatened and where their basic human needs (such as food,

shelter and medical needs) can be met.”35

A narrow construction of the place of safety might lead to the conside- ration that any port where basic needs are satisfied would comply with the requirements to be considered a safe place.36 However, some scholars believe that the obligation on the coastal State to allow disembarkation is implicit in the SAR Convention.37

This runs in parallel with the principle of non-refoulement.38 The Guideli- nes on the Treatment of Persons Rescued at Sea state “[t]he need to avoid disembarkation in territories where the lives and freedoms of those alleging a well-founded fear of persecution would be threatened is a consideration in the case of asylum-seekers and refugees recovered at sea.”39 In short, a place of safety understood within the meaning of the SAR Convention must be interpreted in accordance with refugee law and human rights provisions. A place cannot be deemed safe for refugees simply because distress at sea has

been prevented; it is only safe when non-refoulement is guaranteed.40

In response to this situation, the Facilitation Committee of IMO41 adop- ted principles regarding disembarkation of persons rescued at sea which specify that “[i]f disembarkation from the rescuing ship cannot be arranged swiftly elsewhere, the Government responsible for the SAR area should ac- cept the disembarkation of the persons rescued in accordance with immigra- tion laws and regulations of each Member State into a place of safety under its control in which the persons rescued can have timely access to post rescue support.”42

Despite this initiative, the principles have not been successfully incorpo- rated into the SAR Convention. Today it is considered that the coastal State has only the obligation to ensure that a place of safety is provided to rescued people without being under an explicit obligation to allow disembarkation on its own territory.43

How does this apply to the Maltese case? Malta has formally objected the amendments to the SAR Convention and has entered reservations con- cerning the Facilitation Committee’s abovementioned principles.44 Its main neighbour involved in rescue operations, Italy, did agree to the amendments. In substantive terms, this means that whereas Malta is bound to ensure the disembarkation of persons rescued within its SAR region at the nearest safe port, Italy’s understanding of disembarkation in the SAR regime is that this ought to occur in the State responsible for the SAR region. This leads to constant diplomatic rows as to which State is responsible to operate rescues or disembark migrants who have been rescued by seafarers, particularly in

those cases where persons are rescued within Malta’s SAR region, but geo- graphically closer to Lampedusa.45

A clear example is found in the Pinar E incident. In April 2009, a Turkish owned and Panamanian registered vessel M/V Pinar E rescued over 140 mi- grants 41 nautical miles off the coast of Lampedusa, and approximately 114 nautical miles from Malta. The ship and the rescued migrants were the sub- ject of an ensuing diplomatic clash between Italy and Malta regarding who would receive the migrants. While Malta insisted that the M/V Pinar E would take the migrants to the nearest port, namely, Lampedusa; Italy maintained that the persons were rescued in the Maltese SAR region and urged Malta to take responsibility. Although Italy finally agreed to allow the disembarkation in Sicily, the decision was made exclusively in consideration of the painful humanitarian emergency aboard the cargo ship. Italy made clear that its ac- ceptance of the migrants must not in any way be understood as a precedent nor as a recognition of Malta’s reason for refusing them.46

The situation has worsened due to the political developments in Italy. The issuance of the Code of Conduct for NGOs undertaking Activities in Migrants’ Rescue Operations at Sea47 placed significant restrictions on NGO activities, where failure to comply effectively meant refusal of disembarkation into Italy. A change in government in 2018 led the then Italy’s deputy prime minister to adopt a stricter approach to disembarkation.48 Furthermore, in August 2019, Italy passed a law which limits the entry of NGO humanitarian vessels in Italian territorial waters for reasons of public order and security.49

The standoffs have been recurrent. In December 2018, two German-fla-

gged vessels, the Sea Watch 3 and the Sea-Eye rescued 32 people and 17 mi- grants, respectively and were denied permission to land in Italy and Malta. After 19 days stranded at sea, migrants were allowed to land in Malta.50

In 2019 El Hiblu I, a vessel registered in Palau sailing from Turkey to Libya, responded to a distress alert and embarked almost a hundred migrants and proceeded towards his next port of call, namely, Tripoli.51 After the mi- grants realized they were being returned to Libya, they threatened crew mem- bers. Faced with the difficulty of reaching Libyan coast due to the internal riot, the vessel headed north. Both Italy and Malta initially refused entry of El Hiblu I, but it was finally allowed to disembark the rescues in Maltese ports.52 On 14 August 2019, the Administrative Tribunal of the Lazio Region (Italy) issued an injunction to the Government to let the vessel Open Arms, with 147 rescued migrants on board, to enter Italian territorial sea due to cir- cumstances of exceptional gravity and urgency.53 Italy and Malta had refused

permission to dock and unload the migrants.

All these cases show the discrepancy between the Maltese perception of place of safety in terms of search and rescue and the place of safety in terms of humanitarian law.54 The main point of resistance is the great extent of its SAR region, which makes that the closest safe port of call from the place of rescue is often located in Lampedusa.55

The express reference to the “guidelines developed by the Organiza-

tion” in 2004 Amendments to SAR Convention56 has given it a boost, at least among State parties, as they must be taken into account when implementing SAR obligations. Malta did not accept the amendments neither the Guideli- nes on the Treatment of Persons Rescued at Sea and does not recognise the link between the two approaches which is reflected in these instruments.57

IV. DISTRESS: A HUMANITARIAN OR A SECURITISED TERM?

According to the SAR Convention, the distress phase is defined as “[a] situation wherein there is reasonable certainty that a person, vessel or other craft is threatened by grave and imminent danger and requires immediate assistance.”58

As stated in The Eleanor case,59 the distress must be something of a grave necessity that entails urgency, but not necessarily an actual physical necessity. This is reflected in the SAR Convention as follows:60

Unless otherwise agreed between the States concerned, a Party should authorize, subject to applicable national laws, rules and regulations, immediate entry into or over its territorial sea or territory of rescue units of other Parties solely for the pur- pose of searching for the position of maritime casualties and rescuing the survivors of such casualties.

In the Rainbow Warrior case, the arbitral tribunal took a broader view in- cluding “circumstances of extreme urgency involving medical or other con- siderations of an elementary nature” as circumstances reflecting distress.61

The concept of distress cannot just be considered in situations of force majeure. Overcrowded and unseaworthy vessels traversing the Mediterranean Sea are de facto in distress due to the imminent danger, and hence there is an obligation to render assistance. Moreno-Lax even suggests that unseawor-

thiness per se entails distress.62 This is consonant with the rationale of search and rescue operations, which is exclusively the protection of human beings.63 There are clearly strong humanitarian grounds to provide assistance “regard- less of the nationality or status of such a person or the circumstances in which that person is found”64 and to treat rescued people “with humanity, within the capabilities and limitations of the ship.”65

Although the search and rescue system has its own international legal regime, it is increasingly associated with migration issues, which has distorted the primary humanitarian object of the regime66.

A restrictive interpretation of distress would lead to the conclusion that the obligation to render assistance would not apply to a vessel that is not well equipped, yet not in immediate danger of being lost.67 However, if a broader construction is advanced, a vessel which is not in imminent peril, but over- loaded and unfit for the sea journey, and therefore, very vulnerable to many hazards, may fall under the term distress. The likeliness getting into a very perilous situation in the proximate future would justify this view. This is the situation in which many boats carrying migrants and asylum seekers usually find themselves.68

It is clear that unseaworthy vessels threaten the life of persons aboard. Talking of distress at sea, is an actual danger required or a threat of danger enough? An excessively flexible definition would encourage some vessels to

leave in poor conditions with the intent of needing a rescue. However, this potential call effect cannot hamper a humanitarian base system of rescue of stranded people at sea.

In the present case, Malta defines unseaworthiness as a ship which is “unfit to proceed to sea without danger to human life, property or the marine environment.”69 It extends the interpretation of unseaworthiness to include “undermanning; overloading or unsafe or improper loading; unfamiliarity by the master or the crew with essential shipboard procedures relating to the safety of ships.”70

Malta follows the definition of distress drawn directly from the SAR Con- vention. A distress situation is one in which persons are faced with imminent danger at sea and require immediate assistance, and where failure on the part of the Armed Forces of Malta to intervene in the most expeditious manner possible would result in injury or death.71

V. MALTA, AT THE CROSSROADS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Located in the heart of the Mediterranean Sea, Malta has been considered as a gateway to the European Union over the last fifteen years. Its vast SAR region stretches all across the Mediterranean basin and includes areas that are geographically closer to Italian ports than to its own. It shares boundaries with its maritime neighbours in this regard, namely, Italy, Libya and Greece. Tunisian SAR region has not been established yet.

As mentioned above, Malta objected the 2004 Amendments to SAR Con- vention. Agreeing to the amendments would have made Malta responsible for nearly every search and rescue operation across the Mediterranean. Faced with this prospect, the Maltese Government has consistently made it clear that it does not recognise the amendments.

The existing issues with Italy has been dealt under Part III above with a long list of vessels which found themselves caught in a diplomatic impasse.

Regarding the requested co-operation and co-ordination with Libya, on 18 March 2009, Libya and Malta signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in the field of search and rescue, aimed at coordinating the search and rescue operations within their respectives SAR regions

The MoU provides that both countries coordinate, cooperate and support each other for search and rescue operations within their respective SAR re- gions. Both sides also agreed to authorize their RCCs to request assistance via the rescue centre of the other country and to provide all information on the distress situation in their respective SAR region. It also provides for joint search and rescue training for inter-operability purposes, exchange of visits and training at the Armed Forces of Malta SAR Training centre apart from periodic meetings of representatives of both sides to ensure continued, en- hanced cooperation.73

The Armed Forces of Malta confirmed that the Libyan coastguard beca- me slightly more effective and carried out some rescue operations.74 Howe- ver, the MoU took a back seat due to the armed conflict in Libya.75

Eight years later, in August 2017, the Libyan authorities declared the es- tablishment of its SAR region. Libya withdrew the application for the es- tablishment of the SAR region in December 2017.76 This withdrawal was followed by the submission of a new notification on 14 December.77 In June 2018, IMO publicised the coordinates of the Libyan SAR region in the Glo- bal Integrated Shipping Information System.

In a meeting with the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNS- MIL) in October 2018, the spokesperson of the Libyan Coast Guard con- firmed extending Libya’s SAR region to 94 nautical miles off its coast, as of August 2017, and assuming coordination of operations in that zone with the support of the Italian RCC.78 Indeed, Italy endorsed the declaration of the Libyan SAR region.79

s far as we are concerned, Libya has not completed the procedures in

establishing search and rescue services. It is not clear when the Libyan SAR region may be expected to be fully functional. The question then remains: can Libya be considered a place of safety for the purpose of disembarkation following interception at sea?

establishing search and rescue services. It is not clear when the Libyan SAR region may be expected to be fully functional. The question then remains: can Libya be considered a place of safety for the purpose of disembarkation following interception at sea?

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UN- HCR), Libya does not meet the criteria for a place of safety given the volatili- ty of the country and compromised safety, as well as the considerable risk of those returned being subjected to serious human rights violations and abuses, including prolonged arbitrary detention in inhuman conditions, torture and other ill-treatment, unlawful killings, rape and other forms of sexual violence, forced labour, extortion and exploitation.80

Within this legal framework, the news on attempts of disembarkation and diplomatic rows are continual. Just considering the last few months, alarming headlines report one after the other. In January 2019, 32 migrants rescued by the vessel Sea Watch 3 were in limbo for nearly three weeks until Malta opened its doors, as part of a redistribution deal involving nine countries. Another

17 migrants on another ship, the Sea Eye, arrived in Malta as part of the same arrangement after waiting for two weeks. In March 2019, the vessel El Hiblu 1 intended to send the migrants back to Libya. But several migrants, fearful of returning to that country, allegedly overtook the boat by force and directed it toward Malta. Maltese special forces unit stormed the boat, regained con- trol, and escorted it to port, where the migrants were allowed to disembark. In April 2019, Italy and Malta both denied the vessel Sea Eye port entry; the migrants ultimately disembarked in Malta with military patrol boats, to be dis- tributed among four countries. In June 2019, the vessel Sea Watch rescued the migrants, headed toward Italy, and was ordered not to enter Italian territorial waters. The boat remained in international waters until its 14th day at sea with the rescued migrants, when the captain decided to defy Italian orders and head toward the island of Lampedusa. In August 2019, Malta offered to take only 39 migrants aboard the ship, and not the additional 121 migrants which had been on the vessel Open Arms for nine days.81 After 19 days, the rescuees disembarked in Lampedusa.

Despite these regretful events, Maltese SAR region is a unilateral declara- tion subject to the principle of good faith. The SAR Convention only com- pels States to co-ordinate search and rescue services in the area under their responsibility. Thus, there is no obligation for States to do this individually as they can act in co-operation with other States.82 Arguably, failure to co-ope- rate is worthy of criticism, but difficult to prosecute (unless provided in the domestic legislation) since IMO itself has no powers to enforce the SAR Convention.

VI. CONCLUSIONS

The application or not of the 2004 Amendments to the SAR Convention, along with the dearth of resources to operate the Libyan SAR region and the influx of migrants in the Central Mediterranean route hinder the possibility of finding a speedy solution.

The 2004 Amendments to the SAR Convention and the body of soft law developed by IMO have offered some guidance on SAR operations. Howe- ver, the Guidelines on the Treatment of Persons Rescued at Sea and the Principles relating to Administrative Procedures for Disembarking Persons Rescued at Sea are not binding, so the major issue remain unresolved: where can the rescued people be disembarked within the current legal framework?

Two currents of thought exist about the concept of place of safety and the primary responsibility of the State responsible for the SAR region. The first holds that the State in question has an implicit obligation to allow di- sembarkation when all efforts to find a place of safety have been exhaus- ted.83 The second argues that the primary responsibility relates only to ensure co-ordination and co-operation, so the disembark will be in the closest safe port of call from the place of rescue.

The lack of agreement has rendered the situation more dependent of the political goodwill of States to accept disembarkation, as they generally either refuse or require sharing of persons aboard between States before authori- sing disembarkation.84

The ratification of the 2004 Amendments to the SAR Convention by Malta would represent a major achievement since most of the coastal States of the Mediterranean basin85 would speak the same language. Implementing the amendments would ensure that the obligation of the master to render assistance is complemented by a corresponding obligation to co-operate in rescue situations, thereby relieving the master of the responsibility to care for survivors, and allowing individuals who are rescued at sea in such circumstan- ce to be delivered promptly to a place of safety.86

Additionally, the follow-up of the Guidelines and the Principles would clarify the implications of the notion of place of safety. Logically, the pur-

pose of any rescue operation is to save lives, consequently, survivors cannot be conducted to a place where they might be subject to further risks or per- secution87; however, the refusal of entry into Maltese ports also leads to vul- nerable situations. As found above, co-operation and co-ordination cannot be neglected.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

– ATTARD, F.G., The Duty of the Shipmaster to Render Assistance at Sea under International Law, Ph.D. thesis submitted to the IMO International Maritime Law Institute, 2019.

– BAILLET, C., “The Tampa Case and its Impact on Burden Sharing at Sea”, Human Rights Quarterly, vol. 25, no. 3, 2003.

– BARNES R., “The International Law of the Sea and Migration Control”, in RYAN, B., MIT- SILEGAS, V. (eds), Extraterritorial Immigration Control: Legal Challenges, Martinus Nijhoff, Leiden, 2010, pp. 103-150.

– BARNES, R., “Refugee Law at Sea”, 53 International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 2004.

– BARNES, R., “The International Law of the Sea and Migration Control”, in RYAN, B., MIT- SILEGAS, V., (ed.), Extraterritorial Immigration Control: Legal Challenges, Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy in Europe, vol. 21, Brill, 2010.

– COPPENS, J., “The Essential Role of Malta in Drafting the New Regional Agreement on Migrants at Sea in the Mediterranean Basin”, 44 Journal of Maritime Law and Commerce 89, 2013.

– COPPENS, J., “Search and Rescue”, in PAPASTAVRIDIS, E., TRAPP, K.N., La criminalité en mer, Académie de Droit International de la Haye, Martinus Nijhoff, Leiden, 2014, pp. 381-427.

– COPPENS, J., SOMERS, E., “Towards New Rules on Disembarkation of Persons Rescued at Sea”, International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, vol. 25, 2010.

– DI FILIPPO, M., “Irregular Migration Across the Mediterranean Sea: Problematic Issues concerning the International Rules on Safeguard of Life at Sea”, Paix et Sécurité Internationales, no 1, 2013, pp. 53-76.

– DÍAZ TEJERA, A., “The interception and rescue at sea of asylum seekers, refugees and irregular migrants”, Report of the Committee on Migration, Refugees and Population to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, 1 June 2011, Doc. 12628.

– FISCHER-LESCANO, A., LÖHR, T., TOHIDIPUR, T., “Border Controls at Sea: Require- ments under International Human Rights and Refugee Law”, International Journal of Refugee Law, vol. 21, Issue 2, 2009, pp. 256–296.

– FRIGO, M., “Is Salvini closing just harbours or also the Rule of Law?”, International Com- mission of Jurists, 20 August 2019, https://www.icj.org/is-salvini-closing-just-harbours-or-also- the-rule-of-law/ (accesed on 28 September 2019).

– GALLAGHER, A.T., DAVID, F., The International Law of Migrant Smuggling, Cambridge Uni- versity Press, Cambridge, 2014.

– GHEZELBASH, D., MORENO-LAX, V., KLEIN, N., OPESKIN, B., “Securitization of

Search and Rescue at Sea: The Response to Boat Migration in the Mediterranean and Offshore Australia”, International and Comparative Law Quarterly, vol. 67, 2018, pp. 315-351.

– KLEPP, S., “A Double Bind: Malta and the Rescue of Unwanted Migrants at Sea, A Legal Anthropological Perspective on the Humanitarian Law of the Sea”, 23 International Journal of Refugee Law 538, 2011.

– KOMP, L-M., “The Duty to Assist People in Distress: An Alternative Source of Protection against the Return of Migrants and Asylum Seekers to the High Seas?”, in MORENO-LAX, V., PAPASTAVRIDIS, E., (ed.), Boat Refugees’ and Migrants at Sea: A Comprehensive Approach. Integrating Maritime Security with Human Rights, International Refugee Law Series, vol. 7, Brill, Leiden, 2016.

– MALLIA, P., Migrant Smuggling by Sea Combating a Current Threat to Maritime Security through the Creation of a Cooperative Framework, Publications on Ocean Development, vol. 66, Brill, Leiden, 2009.

– MORENO-LAX, V., “Seeking Asylum in the Mediterranean: Against a Fragmentary Reading of EU Member States’ Obligations Accruing at Sea”, 23 International Journal of Refugee Law 174, 2011.

– MULQUEEN, M., SANDERS, D., SPELLER, I., Small Navies: Strategy and Policy for Small Navies in War and Peace, Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies Series, Routledge, New York, 2014.

– PAPANICOLOPULU, I., “The duty to rescue at sea, in peacetime and in war: A general over- view”, International Review of the Red Cross, vol. 98, no. 2, 2016, pp. 491–514.

– PAPASTAVRIDIS, E., “Rescuing ‘Boat People’ in the Mediterranean Sea: The Responsibi- lity of States under the Law of the Sea”, Blog of the European Journal of International Law, https://www.ejiltalk.org/rescuing-boat-people-in-the-mediterranean-sea-the-responsibility-of- states-under-the-law-of-the-sea/ (accessed on 5 August 2019).

– RATCOVICH, M., “The Concept of ‘Place of Safety’: Yet Another Self Contained Maritime Rule or a Sustainable Solution to the Ever-Controversial Question of Where to Disembark Mi- grants Rescued at Sea?”, Australian Year Book of International Law, vol. 33, 2015.

– ROTHWELL, D. R., “The Law of the Sea and the MV Tampa Incident: Reconciling Maritime Principles with Coastal State Sovereignty”, Public Law Review, vol. 118, 2002.

– TONDINI, M., “The Legality of the Interception of Boat People Under Search and Rescue and Border Control Operations”, Journal of International Maritime Law, vol. 18, 2012.

– TREVISANUT, S, “Search and Rescue Operations in the Mediterranean: Factor and Co-ope-

ration or Conflict?”, International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, vol. 25, 2010, pp. 523-542.

References

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982, entered into force on 1 November 1994

Although Article 98 is located in the Part of UNCLOS con- cerning the high seas, it is submitted that the duty in question applies in all maritime zones.

international Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea of 1 November 1974, entered into force on 25 May 1980

nternational Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue of 27 April 1979, entered into force on 22 June 1985

There is a true distinction between the duty to “assist” and the duty to “res- cue.” According to the SAR Convention, search is “[a]n operation, normally co-ordinated by a rescue coordination centre or rescue sub-centre, using available personnel and facilities to locate persons in distress” (Annex 1.3.1), while rescue is “[a]n operation to retrieve persons in distress, provide for their initial medical or other needs, and deliver them to a place of safety” (Annex 1.3.2).

The Duty to Assist People in Distress: An Alternative Source of Protection against the Return of Migrants and Asylum Seekers to the High Seas?”

Malta is rarely the intended destination for migrants; most aim at landing in Italy and either end up accidentally on Maltese territory or, more commonly, are rescued within the Maltese SAR region and subsequently disembarked in Malta.

“A study on smuggling of mi- grants: Characteristics, responses and cooperation with third countries Case Study 2: Ethio- pia–Libya–Malta/Italy”, 2016.

Search and Rescue

The Maritime Safety Committee deals with all matters related to maritime safety and mari- time security which fall within the scope of IMO, covering both passenger ships and all kinds of cargo ships

Resolution MSC.70(69), adopted on 18 May 1998, adoption of Amendments to the Inter- national Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue, 1979.

Resolution MSC.155(78), adopted on 20 May 2004, adoption of Amendments to the Inter- national Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue, 1979, as amended

On 26 August 2001, M/V Tampa, a Norwegian container ship, was asked by the Australian RCC to assist in the search and rescue operation for an Indonesian ship, the Palapa I, in the waters between Indonesia and Christmas Island (Australia). The Tampa diverted from its course and found the Indonesian ship in a sinking condition approximately 75 nautical miles off Christmas Island. After having rescued and taken on board 438 persons (most of whom were asylum-seekers from Afghanistan) the Tampa resumed its northbound voyage with the plan to disembark the rescued persons along the way in Indonesia about 250 nautical miles to the north. However, the course was changed and set for Christmas Island in response to pressure from some of the rescued persons. This led Australian authorities to inform the master of the Tampa that the Australian territorial sea was closed to the ship and that the course should be changed for Indonesia and that failure to do so would lead to prosecution for people smuggling. After waiting a couple of days offshore Christmas Island and the health condition of some of the rescued persons began to deteriorate, the Tampa issued a distress signal and headed towards Christmas Island. Within short, the Tampa was boarded by Australian special military forces. The rescued asylum-seekers were eventually transferred to an Australian warship that would take them to Papua New Guinea, from where they would be transported to Nauru and New Zealand for further processing. RAtCOviCH, M., “The Concept of ‘Place of Safety’: Yet Another Self Contained Maritime Rule or a Sustainable Solution to the Ever-Controversial Question of Where to Disembark Migrants Rescued at Sea?”, Australian Year Book of International Law, vol. 33, 2015, p. 1-2; ROtHwell, D. R., “The Law of the Sea and the MV Tampa Incident: Reconciling Maritime Principles with Coastal State Sovereignty”, Public Law Review, vol. 118, 2002, p. 118; BARneS, R., “Refugee Law at Sea”, 53 International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 2004, p. 47-48; BAillet, C., “The Tampa Case and its Impact on Burden Sharing at Sea

Maltese authorities maintain that disembarkation must occur at the nearest safe port, which, as a result of the size of Malta’s SAR region and the coordinates of rescues performed by the Armed Forces of Malta, is often Lampedusa.

Status of IMO Treaties. Comprehensive information on the status of multilateral Conventions and instruments in respect of which the International Maritime Organization or its Secretary-General performs depositary or other functions”, September 2019.

Italy/Malta: Obligation to safeguard lives and safety of mi- grants and asylum seekers”

“The Essential Role of Malta in Drafting the New Regional Agreement on Migrants at Sea in the Mediterranean Basin”

In this regard, Papanicolopulu states: “The provision assumes that relevant States will coordinate and, while the State responsible for the SAR zone has primary responsibility, this responsibility relates only to ensuring such co-ordination and co-operation occurs.

The International Law of the Sea and Migration Control”, in RyAn, B., Mit- SileGAS, v. (eds),

he rescuing vessel cannot be seen as a place of safety: “An assisting ship should not be considered a place of safety based solely on the fact that the survivors are no longer in immediate danger once aboard the ship. An assisting ship may not have appropriate facilities and equipment to sustain additional persons on board without endangering its own safety or to properly care for the survivors. Even if the ship is capable of safely accommodating the survivors and may serve as a temporary place of safety, it should be relieved of this responsibility as soon as alternative arrangements can be made.” (para. 6.13).

“Irregular Migration Across the Mediterranean Sea: Problematic Issues concerning the International Rules on Safeguard of Life at Sea”

[w]hile international maritime law does not formally impose upon States an obligation to grant boat people access to their territory, it is clear that - in practice - the ‘disembarkation burden’ rests primarily upon the warship’s flag state, with the SAR co- ordinating state concurring.” tOnDini, M., “The Legality of the Interception of Boat People Under Search and Rescue and Border Control Operations”, Journal of International Maritime Law, vol. 18, 2012, p. 63; FiSCHeR-leSCAnO, A., lÖHR, t., tOHiDipuR, T., “Border Controls at Sea: Requirements under International Human Rights and Refugee Law

The non-refoulement principle operates with respect to individuals in need of protection or where there are substantial grounds for believing that the person concerned faces a real risk of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment upon return or extradition

The Facilitation Committee deals with matters related to the facilitation of international maritime traffic, including the arrival, stay and departure of ships, persons and cargo from ports

Rescuing ‘Boat People’ in the Mediterranean Sea: The Responsibility of States under the Law of the Sea”

The interception and rescue at sea of asylum seekers, refugees and irregular migrants

The International Law of the Sea and Migration Control”

Codice di Condotta per le ONG Impegnate nelle Operazioni di Salvataggio dei Migranti a Mare, Ministero dell’Interno, 18 July 2017.

“The Duty of the Shipmaster to Render Assistance at Sea under Interna- tional Law”

Captain Feared Death In Migrant Hijack At Sea”, The Malta Independent, 29 March 2019

Is Salvini closing just harbours or also the Rule of Law?

“A Double Bind: Malta and the Rescue of Unwanted Migrants at Sea, A Legal Anthropological Perspective on the Humanitarian Law of the Sea

Arbitral Award, Case concerning the difference between New Zealand and France con- cerning the interpretation or application of two agreements, concluded on 9 July 1986 be- tween the two States and which related to the problems arising from the Rainbow Warrior Affair, New Zealand v. France, 30 April 1990, 10 UNRIAA 215, para. 79.

“Seeking Asylum in the Mediterranean: Against a Fragmentary Reading of EU Member States’ Obligations Accruing at Sea

As explained by GHezelBASH et al.: “[T]he increasing linkage between this regime and migration control has begun to infuse SAR with similar characterizations and responses to those seen in relation to irregular migration and its portrayal as ‘a threat’. The basis for the shifting approach, away from the core focus of humanitarian assistance, is the use of a ‘secu- ritization frame’, which assists in understanding why States take certain actions in response to boat migration.

“Malta, Libya, reach search and rescue agreement

MOU Signed in Tripoli: Malta, Libya, to cooperate in search and rescue operations

Non-Governmental Organisations and Search and Rescue at Sea

Desperate and Dangerous: Report on the hu- man rights situation of migrants and refugees in Libya

Following the Libyan declaration, Italy’s then Minister for Foreign Affairs, Angelino Alfa- no, stated that Libya’s actions meant that “balance is being restored in the Mediterranean”. He said the Libyan government was “ready to put in place a search and rescue zone in its waters, work with Europe and invest in its coast guards.” “Italy Works with Libyans to Stop Migrants and Control NGOS

“Desperate and Dangerous: Report on the human rights situation of migrants and refugees in Libya

A year of standoffs over rescued Mediterranean migrants

Search and Rescue Operations in the Mediterranean: Factor and Co-oper- ation or Conflict?

albania, Algeria, Croatia, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Lebanon, Libya, Monaco, Monte- negro, Morocco, Slovenia, Spain, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey have already accepted them