1. Introduction

The eradication of a pest raises questions about the species role in the environments it inhabits, its ecological interactions network and, ultimately, what harmful effects the control program could cause on the ecosystems. Currently, the eradication of the New World Screwworm (NWS) fly(1), Cochliomyia hominivorax (Diptera: Calliphoridae), an obligatory ectoparasite that causes myiasis in warm-blooded vertebrates, including humans(2), is being discussed in Uruguay. The economic losses due to myiasis for the Uruguayan livestock sector were evaluated through different strategies, and estimated as USD 40-45 million per year(1). In addition, more than 800 human cases annually, mainly among the rural population, are projected based on epidemiological data from the National Livestock Services (DGSG, MGAP)(3)(4)(5). However, an underreporting of human cases is estimated due to the myiasis stigmatizing effect.

The NWS has been eradicated from North and Central America through a Wide Area Integrated Pest Management (WA-IPM) program that integrated the Sterile Insect Technique as its main tool, since 1957, when the control program began in the USA(6)(7)(8). Since 2004, a permanent barrier to releasing of sterile insects has been maintained in the Darién region, on the border between Panama and Colombia, to prevent its reintroduction(7). To our knowledge, no reports of negative impacts of NWS eradication programs on ecosystems or other species have ever been published.

Living organisms interact within the species level and between species in their community through complex networks. The loss of a species in a community can lead to secondary extinctions or cascading effects through its ecological interactions(9)(10). The role of the lost species and the capacity of the remaining species with which it interacts to compensate for its loss are essential for the ecosystem functioning, determining the magnitude of the secondary effects in the ecological community(10)(11)(12).

A preliminary risk analysis of the environmental impact of an NWS fly eradication program in Uruguay indicated that it would not result in significant alterations on ecosystems and ecological interactions(1). As a complement, in this paper we describe the ecological interactions network that the NWS integrates, and assess whether secondary extinctions or cascading effects are likely to occur as a consequence of NWS eradication in Uruguay. Here, we summarize the main results related to the ecological impact of the eradication of the NWS obtained in a consultancy contracted by the IPA (Instituto Plan Agropecuario) and the MGAP (Ministry of Livestock), carried out during 2021 for the social and environmental impact assessment of the eradication program.

2. Ecological interactions

Scientific literature research was carried out to identify the direct ecological interactions of the NWS fly, which yielded a total of 274 documents, of which 79 were included here due to their relevance in describing the main ecological interactions (see the complete list of documents in Supplementary Material).

2.1 Parasitism

The NWS fly is an obligatory ectoparasite of warm-blooded vertebrates because it feeds on living tissues (i. e. myiasis) in its larval stages. The NWS develops its life cycle in an extensive list of hosts, including humans(3)(4)(5)(6). Domestic hosts include all animals of production and companion(2). Myiasis is more frequently described among wild hosts in zoos, and even today, there are few reports in wild animals(13). Some of the wild animals in which myiasis has been recorded are the Texas opossum (Didelphis virginiana texensis [Didelphimorphia: Didelphidae])(14), the water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis [Artiodactyla: Bovidae])(15), the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus [Artiodactyla: Cervidae])(14)(16), the key pygmy deer (O. virginianus clavium)(17), the pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus [Artiodactyla: Cervidae])(18), the fallow deer (Dama dama [Artiodactyla: Cervidae])(17), the wild boar (Sus scrofa [Artiodactyla: Suidae])(19)(20)(21), the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris [Rodentia: Caviidae])(22), the maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus [Carnivora: Canidae])(13), the ocelot (Leopardus pardalis [Carnivora: Felidae])(23), the jaguar (Panthera onca [Carnivora: Felidae])(24), the lesser grison (Galictis cuja [Carnivora: Mustelidae])(25), and the rhea (Rhea americana [Struthioniformes: Rheidae])(18).

Also, C.hominivorax parasites have been described, such as the Trichotrombidium muscarum mite (Acari: Prostigmata), mainly affecting adults(26). This parasite feeds on the hemolymph of its hosts and probably on their eggs(27). The micro-hymenoptera parasitoid wasps Aphaereta laeviuscula (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) and Nasonia vitripennis (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) were recorded parasitizing C. hominivorax pupae(28). In addition, the hymenopterans wasps of the Superfamily Chalcidoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) were also identified in its pupae(29). Finally, the fungus Aspergillus flavus (Fungi: Ascomycota) has been detected in C. hominivorax pupae(29).

2.2 Predation

In its adult phase, some identified predators of C. hominivorax are the spiders Nephila clavipes, Eriophora ravilla, Neoscona oaxacensis (Araneae: Araneidae), Leucauge spp. (Araneae: Tetragnathidae)(30), and spiders of the Family Zoridae (Araneae: Lycosoidea)(29). Nephila clavipes has been recorded in Uruguay(31). Others species were identified as predators of immature phases of C. hominivorax life cycle, such as Chrysomya albiceps (Diptera: Calliphoridae)(32). However, the possible control that it can exert over C. hominivorax is low since it also can damage intact tissues, and its association causes more harm than benefits(32). The ant species Labidus sp., Nomamyrmex sp., Solenopsis sp. and Dolichoderus sp. (Insecta: Hymenoptera) may attack C. hominivorax larvae once they leave the host(29)(33). Also, most beetles of the Family Staphylinidae are predators of living carrion insects(34). Usually, animals with myiasis hide for several days before death, and larvae wander between 0.5 and no more than 2 meters from where they land. If they mature on the dead, they are primarily found on the ground below the carcass(33). The pupae, therefore, tend to appear in aggregations associated with those of carrion flies. Likely many mortality factors operate against prepupae and pupae in soils, including predation by beetles and other insects; however, they play a minor role in limiting the number of flies that develop around carrion(33). According to Little(35) larvae of several species of this Family (Staphylinidae) living in sympatry with adults are predators of pupae and larvae of Diptera, while others live in colonies of ants and termites. Most species feed on Diptera larvae in their adult phase, on tetrapod corpses. In general, they are considered beneficial insects(34).

2.3 Commensalism

The NWS fly presents commensalism interactions, in some cases as commensal, and in others in the role of host. As a commensal, it interacts with species that generate skin or mucosal lesions, attracting and facilitating the oviposition and development of C. hominivorax larvae. Most important species are ticks (Arachnida: Ixodidae), such as Rhipicephalus microplus(36), Rhipicephalus sanguineus(37), Amblyomma maculatum(14)(38)(39), A. aureolatum, A. dubitatum, A. tigrinum and A. triste(37)(39)(40), and Ixodes aragaoi(37)(41). However, A. aureolatum, A. dubitatum, A. tigrinum, A. triste and I. aragaoi do not usually cause severe enough lesions that facilitate the infestation by C. hominivorax larvae (2021 conversation with Tatiana Saporiti; unreferenced). Other lesion-causing species that facilitate NWS infestation are the head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis [Phthiraptera: Pediculidae])(42), the human botfly (Dermatobia hominis [Diptera: Oestridae])(42)(43)(44) and the ship botfly (Oestrus ovis [Diptera: Oestridae])(45). Although C. hominivorax and D. hominis are primary myiasis-causing flies, they do not compete for resources, since their oviposition strategies are highly different.

On the other hand, the NWS fly also interacts with blowflies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) such as Cochliomyia macellaria.(46)(47)(48)(49), Chrysomya albiceps(32)(42), Chrysomya rufifacies(50), Lucilia cuprina(51)(52)(53), Lucilia eximia(51)(52) and Lucilia sericata(51)(54). These other species of Diptera are fundamentally necrophagous, and when present in myiasis, they feed on the necrosed tissues generated. In northern Uruguay, 70.8% of myiasis showed other species of Diptera(55).

Finally, in Libya in 1991, C. hominivorax adults were found infested with the cosmopolitan phoretic mite Macrocheles muscaedomesticae. This mite does not have an affinity for any particular host. It is likely that during the SIT program in Libya, the exposure to M. muscaedomesticae occurred due to the feeding behavior of the NWS fly. Calliphoridae feeds on animal feces to reach ovary maturation when carrion is not available(27).

2.4 Mutualism

An often unrecognized but crucial ecological role of some Calliphoridae is pollination(56)(57)(58)(59)(60)(61). The NWS fly adults feed on flower nectar, which is vitally important for their survival, ovary maturation and reproductive success, due to which they could play a role as pollinators(60). However, abundance studies carried out in various regions using different types of rotten animal and plant baits indicated that the NWS has very low abundances concerning other nectarivorous Calliphoridae, such as C. macellaria and Chrysomya sp.(62)(63)(64)(65), which is expected due to the high resources' availability for necrophagous calliphorids and the bias introduced by the baited traps used. Despite of that it should be noted that rotten liver baits are commonly used in surveys of NWS adults(14)(66). Therefore, the overall contribution of the NWS fly as a pollinator is low relative to that of the other calliphorids with which it cohabits.

Facilitation between Diptera that causes obligatory myiasis is another mutualistic interaction. Wound infestation by NWS larvae does not exclude other species; on the contrary, it highly facilitates its presence and vice versa. Several myiasis-causing species inhabit in Uruguay, such as Chrysomya megacephala, Chrysomya rufifacies and Lucilia sericata(67). But as the parasitism of these species is facultative and, instead, they develop mainly on carrion, the benefit of the interaction with C. hominivorax as a substrate provider is negligible.

2.5 Competition

No competitive interactions were identified between the NWS fly adult phase and other species, since it is a generalist (i. e., nectar, pollen and floral molasses), and food is not a limiting factor. Also, as mentioned before, the NWS fly myiasis does not generate competitive interactions.

In order to investigate the substitution or the increase of myiasis cases by other Calliphoridae after the eradication of C. hominivorax in Panama, larvae found in myiasis cases were taxonomically classified during the first years of the eradication program (1998-2005)(68). Six species were identified: Dermatobia hominis (58%), Lucilia spp. (20%), C. macellaria (19%), C. rufifacies (0.4%), as well as larvae of Sarcophagidae (3%) and Muscidae (0.3%). The authors concluded that the absence of C. hominivorax did not increase myiasis caused by other species, supporting the hypothesis that there are no strong competitive interactions between C. hominivorax and the other species in Panama.

3. Impact of the eradication of the NWS fly on biodiversity

The gradual reduction of NWS fly populations until its eradication in Uruguay can impact the species and ecosystems on the national scale. However, in regions where the Sterile Insect Technique has been applied to control the NWS fly, local eradication usually occurs in less than one year. Nevertheless, it usually takes several years to achieve eradication in the entire region.

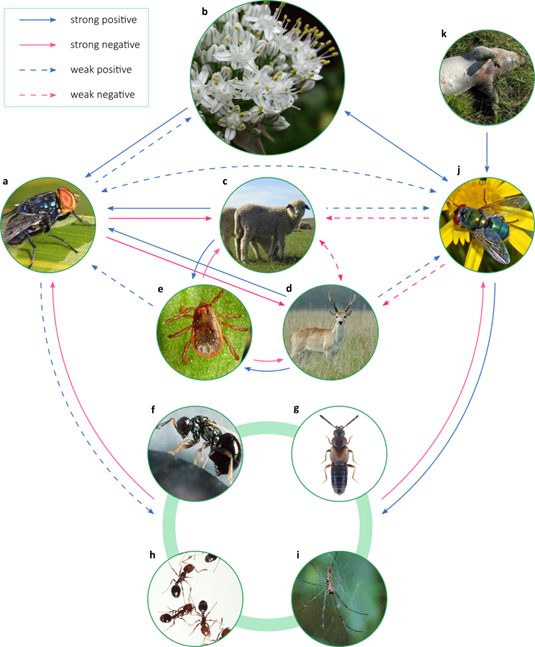

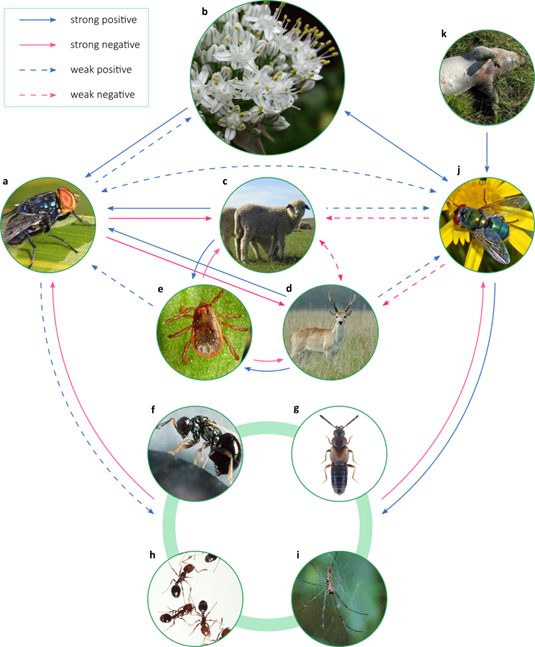

Figure 1

Conceptual synthesis of the NWS fly ecological

interactions network obtained from literature review. Strong effects are those

that may play an important role in regulating the interaction partner of a

species. The images contain representative examples of assemblages of species

that interact with the NWS fly. a:Cochliomyia hominivorax; b: pollinated plants (Allium cepa); c: domestic hosts (Ovis orientalis aries); d: wild hosts (Ozotoceros bezoarticus); e: ectoparasites that facilitate myiasis (Rhipicephalus sanguineus); f-i:

parasitoids and predators; f:

parasitoid microhymenoptera (Nasonia vitripennis); g: predatory staphylinid beetles (Atheta coriaria); h: predatory ants (Solenopsis invicta); i: predatory spiders (Nephila

clavipes); j:

commensal and mutualistic dipterans (Chrysomya albiceps); k:

decomposing tetrapod animals (Sus scrofa

domestica).

Credits: a: Judy Gallagher (Wikimedia Commons) CC BY 2.0; b: pixy.org CCO; c: UBcontributor

(Wikimedia Commons) CC BY-SA 4.0; d: Fedaro

(Wikimedia Commons) CC BY-SA 4.0; e: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain Marck; f: United States

Department of Agriculture (Wikimedia Commons) Public Domain Marck; g: Udo Schmidt

(Flickr) CC BY-SA 2.0; h: Stephen Ausmus

(Wikimedia Commons) Public Domain Marck; i: Ismael Etchevers; j: Hectonichus (Wikimedia

Commons) CC BY-SA 4.0; k: Hbreton19 (Wikimedia

Commons) CC BY-SA 3.0. All

images were cropped

Figure 1

Conceptual synthesis of the NWS fly ecological

interactions network obtained from literature review. Strong effects are those

that may play an important role in regulating the interaction partner of a

species. The images contain representative examples of assemblages of species

that interact with the NWS fly. a:Cochliomyia hominivorax; b: pollinated plants (Allium cepa); c: domestic hosts (Ovis orientalis aries); d: wild hosts (Ozotoceros bezoarticus); e: ectoparasites that facilitate myiasis (Rhipicephalus sanguineus); f-i:

parasitoids and predators; f:

parasitoid microhymenoptera (Nasonia vitripennis); g: predatory staphylinid beetles (Atheta coriaria); h: predatory ants (Solenopsis invicta); i: predatory spiders (Nephila

clavipes); j:

commensal and mutualistic dipterans (Chrysomya albiceps); k:

decomposing tetrapod animals (Sus scrofa

domestica).

Credits: a: Judy Gallagher (Wikimedia Commons) CC BY 2.0; b: pixy.org CCO; c: UBcontributor

(Wikimedia Commons) CC BY-SA 4.0; d: Fedaro

(Wikimedia Commons) CC BY-SA 4.0; e: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain Marck; f: United States

Department of Agriculture (Wikimedia Commons) Public Domain Marck; g: Udo Schmidt

(Flickr) CC BY-SA 2.0; h: Stephen Ausmus

(Wikimedia Commons) Public Domain Marck; i: Ismael Etchevers; j: Hectonichus (Wikimedia

Commons) CC BY-SA 4.0; k: Hbreton19 (Wikimedia

Commons) CC BY-SA 3.0. All

images were cropped

The eradication of a species implies a risk of secondary extinctions and cascading effects which magnitude depends on the ecological role of the species that is lost and the capacity of the rest of the species with which it interacts to compensate for its loss(10)(11)(12). The potential effects of NWS loss, its ecological redundancy with other species, its effect as an indirect regulatory agent of other species, and its participation in critical ecosystem functions are analyzed below. In Figure 1, we present a conceptual synthesis of the network of ecological interactions of NWS described earlier in this work.

The NWS

coexists with other species with similar ecological roles as prey and

pollinator, presenting a high functional redundancy in the communities with

which it interacts(10)(11). This determines a high capacity of ecological

communities to compensate for its loss. The strength of the interactions that

provide redundancy determines the stability of communities in the face of the

disappearance of a species(68). The NWS is one of the calliphorid species with the

lowest densities throughout its range(62)(63)(64)(65). Other calliphorid species that cohabit with the NWS

have similar roles as pollinators, prey, and hosts for parasitoids and phoronts, and exhibit stronger ecological interactions with

partners in these interactions due to their higher densities. This set of

characteristics determines a high functional redundancy in the interactions of

the NWS.

Although the loss of carnivorous parasites can lead to secondary extinctions of other parasites or carnivores(69), the effect of NWS as an indirect regulatory agent of other species through its role as a parasite is neutral. When a parasite exploits and regulates the populations of a particular host type, it can lead to the excessive proliferation of its host relative to other species with which it competes(69). The increase in the populations of its host causes the competitive exclusion of species in the latter's trophic level, leading to they becoming rare(69). Consequently, the populations of other secondary consumers, parasites or carnivores, which exclusively exploit the species affected by competitive exclusion due to the lack of prey, are also reduced(69). However, for this process to occur and cause secondary extinctions, the initially lost parasite must exploit more different resources than the other species of secondary consumers. NWS parasitizes mainly medium and large herbivorous, carnivorous and omnivorous mammals, and to a lesser extent small mammals and birds, but does not show preferences for any particular host. The species competing with the main NWS hosts are other NWS hosts. Therefore, the effect of this parasite as a regulatory agent of competitive exclusion in its lower trophic levels is neutral, and its loss could not cause secondary extinctions derived from this phenomenon.

The MB does not have essential participation in critical functions of the ecosystems. Brody and others(11) identified a group of critical functions for the prevention of secondary extinctions and the maintenance of the structure, biogeochemical processes and resilience of ecosystems. Such critical functions are seed dispersal, predation, disease buffering, phosphorus transport, pollination, engineer species, and foundation species(11). The NWS has a role in the critical function of pollination; however, its contribution is limited or insignificant compared to that of other much more abundant calliphorids in its range that perform the same function. No other critical function is recognized in which the NWS could play an important role.

4. Conclusions and future insights

It is estimated that the NWS presents a high functional redundancy in most of its ecological interactions. Furthermore, it does not play an important role as a regulatory agent of other species and neither in critical ecosystem functions. Therefore, its eradication is unlikely to cause secondary extinctions or cascading effects in the networks of ecological interactions it integrates.

The accuracy of the potential impact assessment of the NWS eradication is limited by the information gaps that certainly exist on its ecological interactions network in Uruguay. In addition, there is a lack of monitoring data or specific research on the effects of NWS eradication in countries where such programs have already been implemented. Therefore, to opportunely detect possible impacts during the course of the program, it is recommended to monitor the ecosystems with a high spatial and temporal resolution, using indicators related to direct and indirect partners in the ecological interactions of the NWS.

References

1. Fresia P, Pimentel S, Iriarte V, Marques L, Durán V, Saravia A, Novas R, Basika T, Ferenczi A, Castells D, Saporiti T, Cuore U, Losiewicz S, Fernández F, Ciappesoni G, Dalla-Rizza M, Menchaca A. Historical perspective and new avenues to control the myiasis-causing fly Cochliomyia hominivorax in Uruguay. Agrocienc Urug. 2021;25(2):e974. doi:10.31285/AGRO.25.974

2. Guimarães J, Papavero N, do Prado A. As miíases na região neotropical (identificação, biologia, bibliografia). Rev bras zool. 1983;1:239416.

3. Basmadjián Y, González Arias M, Galiana A, Palma L, González Curbelo M, Acosta G, Rosa R, Gezuele E. Primera notificación de miasis amigdalina humana por Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel, 1858) en Uruguay. In: VIII Jornadas de Zoología del Uruguay [Internet]. Montevideo: Sociedad Zoologica del Uruguay; 2005 [cited 2022 Aug 19]. p. 37. Available from: https://bit.ly/3H6bWKj.

4. González Arias M, Romero S, González M, Galiana A, Basmadjián Y. Miasis en niños hospitalizados en el Centro Hospitalario Pereira Rossell, Uruguay, 2001-2004. In: XIX Congreso Latinoamericano de Parasitología: libro de resúmenes [Internet]. [place unknown]: Sociedad Científica del Paraguay; 2009 [cited 2022 Aug 19]. p. 257.

5. Manchini T, Fulgueiras P, Fente A. Miasis oral: a propósito de un caso. Odontoestomatologia. 2009;11(12):38-43.

6. Hall M, Wall R. Myiasis of human and domestic animals. Adv Parasitol. 1995;35:256-333.

7. Vargas-Terán M, Spradbery JP, Hofmann HC, Tweddle NE. Impact of screwworm eradication programmes using the sterile insect technique. In: Dyck VA, Hendrichs J, Robinson AS, editors. Sterile insect technique: principles and practice in area-wide integrated pest management. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2021. p. 949-78.

8. Klassen W, Curtis C. History of the Sterile Insect Technique. In: Dyck V, Hendrichs J, Robinson A, eds. Sterile insect technique: principles and practice in area-wide integrated pest management. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. p. 3-36.

9. Petchey OL, Eklöf A, Borrvall C, Ebenman B. Trophically unique species are vulnerable to cascading extinction. Am Nat. 2008;171(5):568-79. doi:10.1086/587068.

10. Kehoe R, Frago E, Sanders D. Cascading extinctions as a hidden driver of insect decline. Ecol Entomol. 2021;46(4):743-56. doi:10.1111/EEN.12985.

11. Brodie JF, Redford KH, Doak DF. Ecological function analysis: incorporating species roles into conservation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2018;33(11):840-50. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.08.013.

12. Sanders D, Thébault E, Kehoe R, van Veen FJ. Trophic redundancy reduces vulnerability to extinction cascades. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(10):2419-24. doi:10.1073/pnas.1716825115.

13. Cansi ER, Bonorino R, Mustafa VS, Guedes KMR. Multiple parasitism in wild maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus, Mammalia: Canidae) in Central Brazil. Comp Clin Path. 2012;21(4):489-93. doi:10.1007/s00580-012-1513-7.

14. Spradbery P. Screwworm fly: a tale of two species. Agricultural Zoology Reviews. 1994;6:1-42.

15. Abdallah SI, Rocha UF, Serra OP, Oba MS, Serra RG. Miíase primária em búfalos--Bubalos bubalis L., 1758--do Estado de São Paulo, Brasil, por Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel, 1858), Diptera Calliphoridae [Prymary myiasis in buffaloes--Bufalos bubais L., 1758--of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, by Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel, 1858), Diptera Calliphoridae]. Rev Farm Bioquim Univ Sao Paulo. 1970;8(1):135-8.

16. Reichard RE. Area-wide biological control of disease vectors and agents affecting wildlife. Rev Sci Tech. 2002;21(1):179-85. doi:10.20506/rst.21.1.1325.

17. USDA. Biological Assessment for a New World Screwworm Eradication Program in South Florida. Washington: USDA; 2017. 26p.

18. Cansi ER. Caracterização das miíases em animais nas cidades de Brasília (Distrito Federal) e Formosa (Goiás) [doctoral’s thesis]. Brasília (BR): Universidade de Brasília; 2011. 120p.

19. Altuna M, Hickner PV, Castro G, Mirazo S, Pérez de León AA, Arp AP. New World screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax) myiasis in feral swine of Uruguay: One Health and transboundary disease implications. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14(1):26. doi:10.1186/s13071-020-04499-z.

20. Brown VR, Bowen RA, Bosco-Lauth AM. Zoonotic pathogens from feral swine that pose a significant threat to public health. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65(3):649-59. doi:10.1111/tbed.12820.

21. Risch DR, Ringma J, Price MR. The global impact of wild pigs (Sus scrofa) on terrestrial biodiversity. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13256. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-92691-1.

22. Wendt LW. Fauna parasitária de capivaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris Linnaeus, 1766) em sistema de criação semi-intensivo, na região sul do Rio Grande do Sul [master’s thesis]. Pelotas (BR): Universidade Federal de Pelotas; 2009. 54p.

23. Pulgar E, Quijada J, Bethencourt A, de Román EM. Reporte de un caso de miasis por Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel, 1858) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) en un cunaguaro (Leopardus pardalis, Linnaeus, 1758) en cautiverio tratado con Doramectina. Entomotropica. 2009;24(3):129-33.

24. May-Junior JA, Fagundes-Moreira R, Souza VB, Almeida BA, Haberfeld MB, Sartorelo LR, Ranpim LE, Fragoso CE, Soares JF. Dermatobiosis in Panthera onca: first description and multinomial logistic regression to estimate and predict parasitism in captured wild animals. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2021;30(1):e023820. doi:10.1590/S1984-29612021003.

25. Figueiredo MAP, Santos ACG, Guerra R de MSNC. Ectoparasitos de animais silvestres no Maranhão. Pesqui Vet Bras. 2010;30(11):988-90. doi:10.1590/s0100-736x2010001100013.

26. Felska M, Wohltmann A, Makol J. A synopsis of host-parasite associations between Trombidioidea (Trombidiformes: Prostigmata, Parasitengona) and arthropod hosts. Syst Appl Acarol. 2018;23(7):1375-479. doi:10.11158/saa.23.7.14.

27. McGarry JW, Gusbi AM, Baker A, Hall MJ, El Megademi K. Phoretic and parasitic mites infesting the New World screwworm fly, Cochliomyia hominivorax, following sterile insect releases in Libya. Med Vet Entomol. 1992;6(3):255-60. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2915.1992.tb00615.x.

28. Rodrigues-Guimarães R, Guimarães RR, De Carvalho RW, Mayhé-Nunes AJ, Moya-Borja GE. Registro de Aphaereta laeviuscula (Spinola) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) e Nasonia vitripennis (Walker) (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) como parasitóide de Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel) (Diptera: Calliphoridae), no estado do Rio de Jane. Neotrop Entomol. 2006;35(3):402-7. doi:10.1590/s1519-566x2006000300017.

29. De Souza JR, Pires MS, Sanavria A. Influência d o clima e da cobertura de solo na mortalidade de Cochliomyia hominivorax (coquerel, 1958) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) e na atuação de seus inimigos naturais. Biosci J. 2010;26(1):136-46.

30. Welch JB. Predation by Spiders on Ground-Released Screwworm Flies, Cochliomyia hominivorax (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in a Mountainous Area of Southern Mexico. J Arachnol. 1993;21(1):23-8.

31. Viera C, editor. Arácnidos de Uruguay: diversidad, comportamiento y ecología. Montevideo: Ediciones de la Banda Oriental; 2011. 237p.

32. Madeira NG. Would Chrysomya albiceps (Diptera: Calliphoridae) be a beneficial species? Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2001;53(2):1-5. doi:10.1590/S0102-09352001000200004.

33. Norris KR. The bionomics of blow flies. Annu Rev Entomol. 1965;10:47-68.

34. Rodrigues-García C. Radiomarcacao de Chrysomya megacephala (Fabricius, 1794) (Diptera, Calliphoridae) e criacao de Belonuchus rufipennis (Fabricius, 1801) (Coleoptera, Staphulinidae) em ovos desta mosca [doctoral’s thesis]. São Paulo (BR): Universidad Estadual de São Paulo; 1993. 88p.

35. Little VA. General and Applied Entomology. 3rd ed. New York: Harper & Row; 1972. 527p.

36. Reck J, Marks FS, Rodrigues RO, Souza UA, Webster A, Leite RC, Gonzales JC, Klafke GM, Martins JR. Does Rhipicephalus microplus tick infestation increase the risk for myiasis caused by Cochliomyia hominivorax in cattle? Prev Vet Med. 2014;113(1):59-62. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.10.006.

37. Venzal JM, Castro O, Cabrera PA, de Souza CG, Guglielmone AA. Las garrapatas de Uruguay: especies, hospedadores, distribución e importancia sanitaria. Veterinaria (Montevideo). 2003;30(150-151):17-28.

38. Estrada-Peña A, Venzal JM, Mangold AJ, Cafrune MM, Guglielmone AA. The Amblyomma maculatum Koch, 1844 (Acari: Ixodidae: Amblyomminae) tick group: diagnostic characters, description of the larva of A. parvitarsum Neumann, 1901, 16S rDNA sequences, distribution and hosts. Syst Parasitol. 2005;60(2):99-112. doi:10.1007/s11230-004-1382-9.

39. Martins TF, Lado P, Labruna MB, Venzal JM. El género Amblyomma (Acari: Ixodidae) en Uruguay: especies, distribución, hospedadores, importancia sanitaria y claves para la determinación de adultos y ninfas. Veterinaria (Montevideo). 2014;50(193):26-41.

40. Nava S, Venzal JM, Labruna MB, Mastropaolo M, González EM, Mangold AJ, Guglielmone AA. Hosts, distribution and genetic divergence (16S rDNA) of Amblyomma dubitatum (Acari: Ixodidae). Exp Appl Acarol. 2010;51(4):335-51. doi:10.1007/s10493-009-9331-6.

41. Saracho-Bottero MN, Venzal JM, Tarragona EL, Thompson CS, Mangold AJ, Beati L, Guglielmone AA, Nava S. The Ixodes ricinus complex (Acari: Ixodidae) in the Southern Cone of America: Ixodes pararicinus, Ixodes aragaoi, and Ixodes sp. cf. I. affinis. Parasitol Res. 2020;119(1):43-54. doi:10.1007/s00436-019-06470-z.

42. Rodríguez Diego J, Olivares Orozco J, Sánchez Castilleja Y, Arece García J. El Gusano Barrenador del Ganado, Cochliomyia hominivorax (Diptera: Calliphoridae): un problema en la salud animal y humana. Rev Salud Anim. 2016;38(2):120-30.

43. Grisi L, Leite RC, Martins JR, Barros AT, Andreotti R, Cançado PH, León AA, Pereira JB, Villela HS. Reassessment of the potential economic impact of cattle parasites in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2014;23(2):150-6. doi:10.1590/s1984-29612014042.

44. Remedios M. Ficha zoológica: Dermatobia hominis Linnaeus, 1781 (Diptera: Oestridae). Noticias de la SZU. 2016;9(34):38-9.

45. Gracia MJ, Ruíz de Arcaute M, Ferrer LM, Ramo M, Jiménez C, Figueras L. Oestrosis: parasitism by Oestrus ovis. Small Rumin Res. 2019;181(January):91-8. doi:10.1016/j.smallrumres.2019.04.017.

46. Christen JA. Molecular-Based Identification of the New World Screwworm, Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) [doctoral’s thesis]. Lincoln (US): University of Nebraska; 2008. 215p.

47. Lyra ML, Hatadani LM, de Azeredo-Espin AM, Klaczko LB. Wing morphometry as a tool for correct identification of primary and secondary New World screwworm fly. Bull Entomol Res. 2010;100(1):19-26. doi:10.1017/S0007485309006762.

48. López VG, Romero MI, Parra-Henao G. Gastric and intestinal myiasis due to Ornidia obesa (Diptera: Syrphidae) in humans: first report in colombia. Revista MVZ Córdoba. 2017;22(1):5755-60. doi:10.21897/rmvz.935.

49. Carrão DL, Hernandez JMF, Cardoso JD, Correia TR, Araújo JL, Ubiali DG. Dacryoadenitis caused by Cochliomyia macellaria (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in a sambar deer (Rusa unicolor) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports. 2021;23:100504. doi:10.1016/j.vprsr.2020.100504.

50. Baumgartner DL, Greenberg B. The Genus Chrysomya (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in the New World. J Med Entomol. 1984;21(1):105-13. doi:10.1093/jmedent/21.1.105.

51. Azeredo-Espin AM, Madeira NG. Primary myiasis in dog caused by Phaenicia eximia (Diptera:Calliphoridae) and preliminary mitochondrial DNA analysis of the species in Brazil. J Med Entomol. 1996;33(5):839-43. doi:10.1093/jmedent/33.5.839.

52. Moretti TC, Thyssen PJ. Miíase primária em coelho doméstico causada por Lucilia eximia (Diptera: Calliphoridae) no Brasil: relato de caso. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2006;58(1):28-30. doi:10.1590/s0102-09352006000100005.

53. Bonino Morlan J, Casaretto A. Principales patologías en los actuales sistemas de producción ovina del Uruguay: una puesta al día. In: XL Jornadas Uruguayas de Buiatría. Paysandú: CMVP; 2012. p.19-29.

54. Farkas R, Hall MJ, Bouzagou AK, Lhor Y, Khallaayoune K. Traumatic myiasis in dogs caused by Wohlfahrtia magnifica and its importance in the epidemiology of wohlfahrtiosis of livestock. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23(Suppl 1):80-5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00772.x.

55. Valledor MS, Petraccia L, Cabral P, Castro O, Décia L, Xavier V, Altuna M, Marques L, Casás G, Dominguez D, Lado P. Resultados del Diagnostico de Bicheras Obtenidas en el Departamento de Artigas Durante 13 Semanas (Enero – Abril 09). In: 6tas Jornadas Técnicas de Facultad de Veterinaria. Montevideo: Facultad de Veterinaria; 2009. p. 1301.

56. Heath AC. Beneficial aspects of blowflies (Diptera: Calliphoridae). N Z Entomol. 1982;7(3):343-8. doi:10.1080/00779962.1982.9722422.

57. Clement SL, Hellier BC, Elberson LR, Staska RT, Evans MA. Flies (Diptera: Muscidae: Calliphoridae) are efficient pollinators of Allium ampeloprasum L. (Alliaceae) in field cages. J Econ Entomol. 2007;100(1):131-5. doi:10.1603/0022-0493(2007)100[131:fdmcae]2.0.co;2.

58. Saeed S, Naqqash MN, Jaleel W, Saeed Q, Ghouri F. The effect of blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) on the size and weight of mangos (Mangifera indica L.). PeerJ. 2016;4:e2076. doi:10.7717/peerj.2076.

59. Oliveira PE, Rech AR. Floral biology and pollination in Brazil: history and possibilities. Acta Bot Bras. 2018;32(3):321-8.

60. Rusch TW, Adutwumwaah A, Beebe LEJ, Tomberlin JK, Tarone AM. The upper thermal tolerance of the secondary screwworm, Cochliomyia macellaria Fabricius (Diptera: Calliphoridae). J Therm Biol. 2019;85:102405. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2019.102405.

61. Paulo DF, Junqueira ACM, Arp AP, Vieira AS, Ceballos J, Skoda SR, Pérez-de-León AA, Sagel A, McMillan WO, Scott MJ, Concha C, Azeredo-Espin AML. Disruption of the odorant coreceptor Orco impairs foraging and host finding behaviors in the New World screwworm fly. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):11379. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-90649-x.

62. Costamagna SR, Visciarelli EC, Lucchi LD, Basabe NE, Esteban MP, Oliva A. Aportes al conocimiento de los dípteros ciclorrafos en el área urbana de Bahía Blanca (provincia de Buenos Aires), Argentina. Rev Mus Argent Cienc Nat. 2007;9(1):1-4.

63. Dufek MI, Oscherov EB, Damborsky MP, Mulieri PR. Assessment of the Abundance and Diversity of Calliphoridae and Sarcophagidae (Diptera) in Sites With Different Degrees of Human Impact in the Iberá Wetlands (Argentina). J Med Entomol. 2016;53(4):827-35. doi:10.1093/jme/tjw045.

64. Luz RT, Azevedo WTA, Silva AS, Lessa CSS, Maia VC, Aguiar VM. Population fluctuation, influence of abiotic factors and the height of traps on the abundance and richness of Calliphoridae and Mesembrinellidae. J Med Entomol. 2020;57(6):1748-57. doi:10.1093/jme/tjaa092.

65. Schnack JA, Mariluis JC, Centeno N, Muzon J. Composición específica, ecología y sinantropía de Calllphoridae (Insecta: Diptera) en el Gran Buenos Aires. Rev Soc Entomol Arg. 1995;54(1-4):161-71.

66. Coronado A, Kowalski A. Current status of the New World screwworm Cochliomyia hominivorax in Venezuela. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23(Suppl 1):106-10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00794.x.

67. Martínez M, Remedios M, Goñi B. Lista de los Calliphoridae (Diptera: Muscoporpha) del Uruguay. Bol Soc zoológica Urug. 2016;25(1):35-51.

68. Bermúdez SE, Espinosa JD, Cielo AB, Clavel F, Subía J, Barrios S, Medianero E. Incidence of myiasis in Panama during the eradication of Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel 1858, Diptera: Calliphoridae) (2002-2005). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102(6):675-9. doi:10.1590/s0074-02762007005000074.

69. Sanders D, Sutter L, van Veen FJ. The loss of indirect interactions leads to cascading extinctions of carnivores. Ecol Lett. 2013;16(5):664-9. doi:10.1111/ele.12096.

Author notes

ismaelec@gmail.com

Additional information

Author contribution statement: All authors conceived, discussed and wrote

the manuscript. The final version of the manuscript was accepted by all

authors.

Editor:: The following editor approved this article. Milka Ferrer (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5501-064X) Universidad de la República, Facultad de Agronomía, Montevideo, Uruguay

Alternative link

http://agrocienciauruguay.uy/index.php/agrociencia/article/view/1056 (pdf)