Introduction

In Mexico, official statistics show the severity of the Violence against Women and Girls (VAWG). The Public Security Secretariat revealed that by September 2023 there were 1,652,144 crimes against women and girls as received by the emergency line 911 . From these, the majority of crimes were abuse in the form of battering, crimes against the freedom including kidnapping and rapture, murder, sexual crimes including human trafficking including sex-slavery. However less than 1% were recorded as femicides (Secretaria de Seguridad y Proteccion Ciudadana, 2023). These statistics demonstrate the alarming nature of VAWG in Mexico, since it is estimated that in Mexico everyday 10.6 women are murdered because of their gender (López Barajas, 2020). Furthermore, while these statistics seem alarming, authors have suggested that the real perpetration statistics might be considerably higher and only a small portion is recorded by authorities (Amnesty International, 2021).

The National Institute for Statistic and Geography (INEGI, 2019) revealed that 1 in 10 femicides in Mexico targets girls under 17. Furthermore, the National Statistic for Dynamics in Relationships at Home (ENDIREH, 2019) reported high percentages of physical, emotional, financial, and sexual violence against women. Data Civica (2019) highlighted a shift in violence patterns, with public space violence surpassing that at home since 2012, coinciding with a tripling of murders of women aged 20-35. Femicide incidents doubled from 2015 to 2021, with a projected increase in towards the end of 2023 (Secretaria de Seguridad y Proteccion Ciudadana, 2023).

Causes of VAWG in

the region

In the Latin American context, VAWG is influenced by unique characteristics. Menjivar and Abrego (2012) note structural and symbolic violence in Central America, where legal institutions fail to protect women effectively. The absence of serious intent further exposes women to institutional violence when seeking help. Central American women, affected by structural violence, increasingly migrate to escape generalised violence that endangers their children (Lopez-Ricoy and Medina, 2022). Soria Escalante et al. (2021) document women's awareness of risks during migration, leading some to form alliances for protection against criminal gangs.

Prieto-Carrón et al. (2007) argue that tensions between criminal groups and politicians contribute to structural violence against women, conveniently blamed on organised crime. Ramos Lira et al. (2016) assert that VAWG is often treated as a side effect of generalised violence and cartel conflicts, perpetuating a cycle of impunity. Soria Escalante et al. (2022) highlight an additional layer of violence, including rape and child abduction, directed at women. Understanding VAWG involves examining perpetrators' justifications rooted in ideas of male dominance and societal biases (Sarmiento et al., 2014). Beliefs that authorise control over women's lives contribute to maintaining social order (Wilson, 2013). In Mexico, violence against women is sometimes justified within communities based on perceived gender roles, with both perpetrator and victim families contributing to this justification (Agoff et al., 2007; Htun & Jensenius, 2022).

Online

Perspectives of VAWG and why it matters?

While limited research explores the online world's role in promoting misogynistic violence, evidence suggests its influence (Harmer & Lewis, 2020). Amnesty International (2017) reports 23% of women in European and English-speaking countries experiencing online abuse, impacting real-life safety. Online spaces, like the Manosphere, facilitate the spread of anti-feminist and sexist beliefs (Tranchese & Sugiura, 2021). The Manosphere and other online tools can exacerbate violence, leading to technology-facilitated coercive control (Dragiewicz et al., 2018). Online abuse's impact extends beyond words, affecting victims' economic stability and productivity (Jane, 2017).

Ging (2019) argues that online discourses, like those in the Manosphere, influence offline actions. The danger of online violence translating into physical harm is evident in incidents involving the incel movement (Hoffman et al., 2020). The incel movement, with connections to terrorist movements, highlights a concerning connection between online misogyny and physical violence (Díaz and Valji, 2019). Baele et al. (2021) advocate classifying incel violence as a form of violent misogyny alongside honour killings and sexual violence. While the Northern hemisphere has seen extensive research on online VAWG, the Southern hemisphere, particularly Latin America, lacks comprehensive studies. Despite being one of the most dangerous places for women, research on online abuse in Mexico is scarce. This study aims to fill this gap by examining online responses to news on VAWG in Mexico, providing insights into societal perceptions and emotions, and informing recommendations for intervention.

For Ging (2019) the Manosphere enables the spread of misogynistic and racist beliefs and attitudes that inherently affect women in a way that it could not be possible without the internet tools. Furthermore, Dragiewicz et al. (2018) conclude that online tools can exacerbate VAWG. Their work documents how online tools have enabled technology facilitated coercive control (TFCC), expanding the abuse from just home-based into constant surveillance through devices such as mobile phones, tablets, social media, to stalking, accessing their accounts without permission, revenge porn, or doxxing. Hence, the impact of online VAWG demonstrate that online abuse can harm its victims beyond “just words” or banter as it can often be trivialised (Gosse, 2021).

Regarding the effects of online gendered violence in terms of costs to its victims, particularly women Jane (2017) explains that victims of cyberhate suffer what she names economic vandalism. Economic vandalism can be understood as the consequences in the work life and productivity of women that have been affected due to harassment experimented online. For example, a decrease in productivity caused by the anxiety created with dealing with online communications, workplace harassment or missed work opportunities. Gosse et al. (2021) note the gendered element in online abuse affecting scholars. While online harassment affects both male and women, it is women who are more frequently targeted by reasons of their gender vs males who are mostly targeted by reasons of their opinion and rank as a faculty member. This mean that when scholars are exposed and attacked online, male will be targeted by their status and opinion while women will be targeted by their characteristics associated to their gender such as appearance, femininity, weight, and other aspects associated to gender and femininity.

The dangers of online violence being translated into physical and face to face violence can largely be exemplified with incidents which have involved the incel movement (Hoffman et.al, 2020). While it has been well established that not all incel members share violent misogynistic beliefs, within the community it is well known the term going ER. Going ER stands for showing the willingness or readiness to perpetrate attacks on women as inspired by Elliot Rodger who holds a celebrity like status within the incel community for perpetrating targeted attacks to attractive women in California in 2004 (Regehr, 2022). For Hoffman et al. (2020) misogynistic violence as exerted by incel identified members must be not taken lightly given that its popularity is expanding beyond North America and its dynamic shows similarities to and has connections with other terrorist movements. Díaz and Valji (2019) have argued that there is a clear connection between misogyny and physically violent extremism. In which the online misogyny acts as an early sign or warning of offline violence. They discuss that in many manosphere sites there is a latent encouragement towards acting violently towards women and girls. Furthermore Baele et al. (2021) argue that Incel violence should be classified alongside other forms of violent misogyny, such as honour killings and sexual violence, issues that are considered as a public health problem since at least a third of the women population are targeted (Amnesty International, 2017)

The impact of online VAWG has been more widely investigated in what is known is criminology as the “Northern hemisphere” with some very thorough examples (Ging & Sapiera, 2019; Jane, 2017). However, more is needed in the called Southern hemisphere where most of its countries have different structural, political and societal characteristics deeply engrained in the collective culture. This is the case for Latin America in which according to the World Bank, 6 out of the 10 most dangerous places to be a woman are in Latin America. Particularly, Mexico is ranked in number 6. Despite the growing demand from women throughout the country for an end to the generalised violence against women and girls, very little literature has documented the extent of online abuse in Mexico, particularly from a qualitative perspective. Given that research into online news readers’ comments remains limited (Graham & Wright, 2015; Harmer & Lewis, 2022; Chan, 2022) despite this online space being rich in user-generated, the nature of these spaces has hardly yet been explored. Furthermore, studies examining the content generated in relation to gender conceptions and misconceptions still relatively scarce and almost inexistent for the Latin American and Mexican contexts respectively. The present research is concerned with the online responses from readers of newspapers whose content focus on the topic of violence against women and girls such as femicides, girl infanticides, human trafficking with the purpose of sexual exploitation, protests against the gendered violence and disappearance of women and girls.

This paper provides an empirically grounded exploration of how, in response to news of VAWG in Mexico, the readers as a reflection of society make sense of the context and conditions that underpin VAWG. Through a thematic analysis of reader’s understanding of the violence, the role of victims, perpetrators, and structural context, we aim to examine the society understanding, emotional and cognitive perception and emotional response to VAWG. This will enable the possibility to make recommendations in terms of sensibilisation, education and intervention to prevent social and online manifestations of VAWG.

Method

This

research derives from an inductive thematic analysis of readers’ comments from 8

online neews about Violence against women and girls

in Mexico. The choice of thematic analysis is to explore how commenters

perceived, made sense and interacted amongst them about the coverage of issues

related to VAWG in Mexico. Thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke (2006)

approach allowed to obtain a general sense of the online interactions and

interpretations about the specific data set.

Materials and

Procedure.

The proposal was approved by the Ethics panel at the University of West London. Once approval was obtained, the first step in the research was to sample online newspapers that covered the subject of VAWG. The inclusion criteria consisted of them being: a) of national circulation and having either a printed version or a You Tube channel alternative endorsed by a national news outlet. These criteria would allow to sample online outlets that are endorsed by established platforms, vs vloggers or influencers who are not adhered to an established media. This also allowed the researcher to clearly identify the editorial tone and political leaning of such outlets. In other words, having sample of conservative and sensationalist editorial lines. Readers could make comments anonymously, from their Facebook accounts, or their YouTube platforms or directly on the comments section of the outlets. The chosen online news platforms were El Gráfico (sensationalist editorial), El Universal (conservative), Milenio (conservative), Excelsior (central), El Mundo (liberal), Nmas (liberal) (See appendix A)

Articles were chosen when their content reported news about VAWG in Mexico and reported different extents and degrees of severity and included cases of femicide, infanticide, kidnapping and disappearance, or news that focused on general statistics about the situation of VAWG in the country, or protests from feminist groups demanding security for women. All eligible articles (49) and their comments sections were reviewed, and a total of eight articles were selected given that the number of comments was deemed to allow for data saturation. The list of articles analysed, and their comments can be found in Appendix B. The number of comments on each article varied, with the lowest number of comments being 154, and the highest number being 1927. The number of comments in the final data set is 5947.

Braun and Clarke’s (2006) approach for thematic analysis was observed in this analysis. Once the news articles where chosen, all the comments produced where pasted in a Word document for analysis. To become familiar with the data, the comments where re-read carefully. This was followed by inductively coded each comment. No restrictions were placed on the number of comments generated. Once the codes were finalised, the research team had a discussion about the coding names and meaning that were assisted by an external member of the team who corroborated that the interpretations in English corresponded to the meaning originally established in Spanish. After all the comments were coded, the codes were grouped in relevant categories. Areas of significant patterns were identified and developed into broader themes. Our results threw four main themes about how readers make sense about the violence against women and girls in Mexico and how they chose to comment about it with other posters. These were: 1) Otherising femicides but normalising VAWG, 2) Denial of VAWG. A matter of blame and 3) Resisting abuse as an invitation for abuse

Analysis

This

research sought to answer the research question of How do online readers (as a

reflection of society) make sense of the context and conditions that underpin

VAWG in Mexico? Data analysis revealed 3 main themes that are explained below.

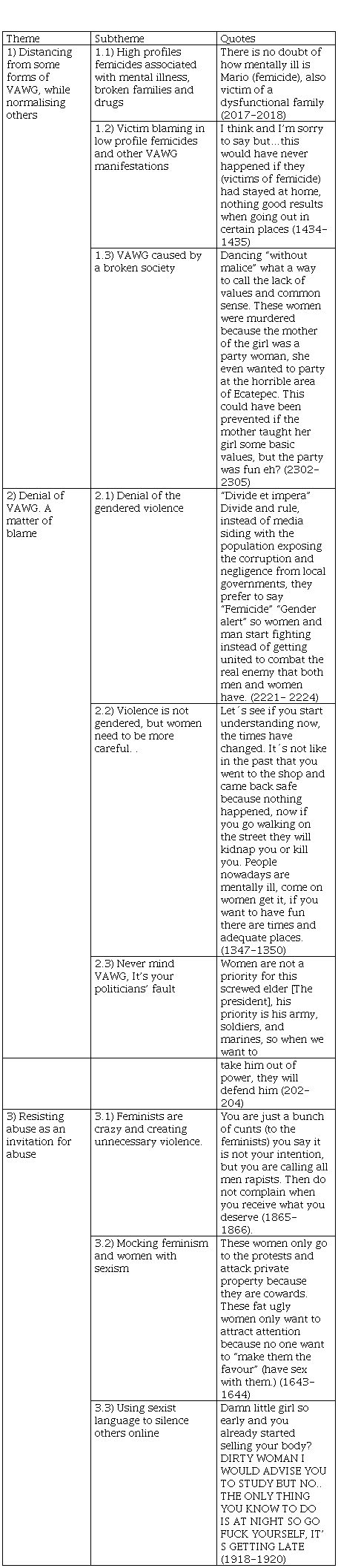

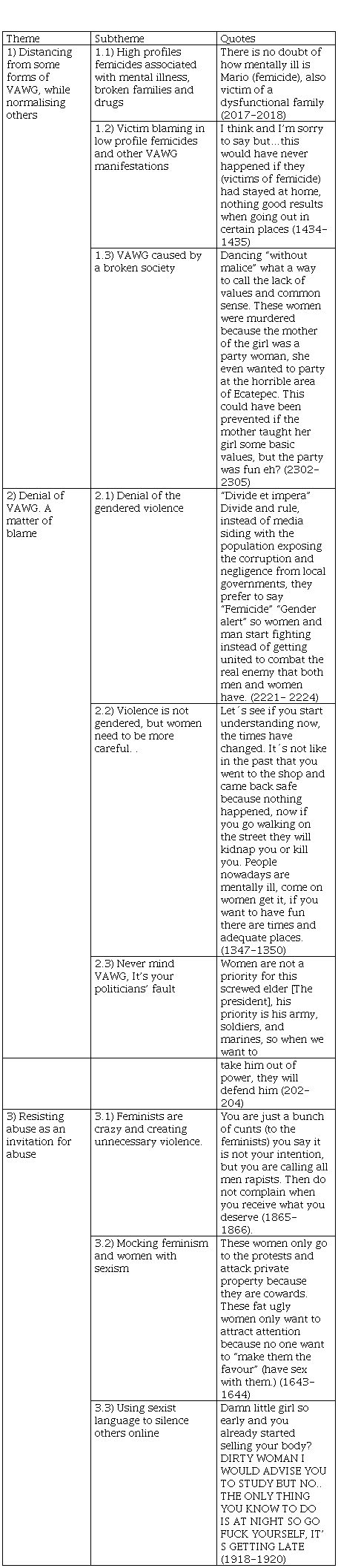

Table 1. How do online readers (as a

reflection of society) make sense of the context and conditions that underpin

VAWG in Mexico?

Braun

and Clarke’s (2006)

Braun

and Clarke’s (2006)

|

Theme

|

Subtheme

|

Quotes

|

|

1) Distancing from some forms of VAWG, while normalising

others

|

1.1) High profiles femicides associated with mental illness, broken

families and drugs

|

There is no doubt of how mentally ill is Mario (femicide), also victim

of a dysfunctional family (2017-2018)

|

|

1.2) Victim blaming in low profile femicides and other VAWG

manifestations

|

I think and I’m sorry to say but…this would have never happened if

they (victims of femicide) had stayed at home,

nothing good results when going out in certain places (1434-1435)

|

|

1.3) VAWG caused by a broken society

|

Dancing “without malice” what a way to call the lack of values and

common sense. These women were murdered because the mother of the girl was a

party woman, she even wanted to party at the horrible area of Ecatepec. This

could have been prevented if the mother taught her girl some basic values,

but

the party was fun eh? (2302- 2305)

|

|

2) Denial of VAWG. A matter of blame

|

2.1) Denial of the gendered violence

|

“Divide et impera” Divide and rule, instead

of media siding with the population exposing the corruption and negligence

from local governments, they prefer to say “Femicide” “Gender alert” so women

and man start fighting instead of getting united to combat the real enemy

that both men and women have. (2221-

2224)

|

|

2.2) Violence is not

gendered, but women need to be more careful. .

|

Let´s see if you start understanding now, the times have changed. It´s

not like in the past that you went to the shop and came back safe because

nothing happened, now if you go walking on the street

they will kidnap you or kill you. People nowadays are mentally ill, come on

women get it, if you want to have fun there are times and adequate places.

(1347-1350)

|

|

2.3) Never mind VAWG, It’s your

politicians’ fault

|

Women are not a priority for this

screwed elder [The president], his priority is his army, soldiers, and

marines, so when we want to

|

| |

take him out of power, they will defend him (202-204)

|

|

3) Resisting abuse as an invitation for abuse

|

3.1) Feminists are crazy and creating unnecessary violence.

|

You are just a bunch of cunts (to the feminists) you say it is not

your intention, but you are calling all men rapists. Then do not complain

when you receive

what you deserve (1865-1866).

|

|

3.2) Mocking feminism and women with sexism

|

These women only go to the protests and attack private property

because they are cowards. These fat ugly women only want to attract attention

because no one want to “make them the favour” (have

sex with them.) (1643-1644)

|

|

3.3) Using sexist language to silence others online

|

Damn little girl so early and you already started selling your body?

DIRTY WOMAN I WOULD ADVISE YOU TO STUDY BUT NO..THE ONLY THING YOU KNOW TO DO

IS AT NIGHT SO GO FUCK YOURSELF, IT’S GETTING

LATE (1918-1920)

|

Otherising

femicides but normalising VAWG

This

theme identified patterns of data that reflected the perception of commenters

about the perpetrators’ profile and some of the reasons behind their offending.

It was noted that in general, the reasons attributed to the VAWG were

circumstances that “made” or “pushed” the perpetrators to offend. What is

interesting about these pushes is that in the case of high profile femicides or

infanticide; the “pushes” were associated with insanity, or insanity cause by

addictions. However, when the cases were low profile femicides, or other VAWG

manifestations, the pushes were attributed to the society, or even the victims.

High profile femicides associated with

mental illness, broken families and drugs

When readers encountered news considered as high profile femicides characterised by an extreme cruelty in the murder, or the age of the victim in which the victim was an underage girl, many commenters expressed that the behaviour of the perpetrator was caused by a mental illness. It was interesting to note that for some people the mental illness was the result of addictive behaviours as the following commenters noted:

Vile insane man. Only a person with a disturbed mind can carry out such a butcher job and murder of a young woman (48-49)

The stupidity of people reaches so far that they lose control of themselves because of the drugs, because there are testimonies that the mentioned Mario (femicide) is an addict and also the alcohol. It is an insane person in potency (2096-2098)

For other readers the perceived mental disorder of the perpetrators was caused by growing up in a dysfunctional or abusive family as the following readers note:

There is no doubt of how mentally ill is Mario (femicide), also victim of a dysfunctional family (2017-2018)

Now we need to see what the children of those bastards saw, they need to be treated, otherwise in the future we will see these cases to repeat themselves (2058-2059)

Something that resulted interesting in this analysis was that while many commenters assumed mental illness from the perpetrators in these high-profile cases, in the coverage of such notes there was no indication of mental illness. In other words, there is no previous history of mental illness, nor an evaluation presented by experts in the area that could confirm such conclusions made by the commenters. Furthermore, the perpetrators in these cases seemed to live conventional lives. This might reflect that for many people the perpetration of such cruel femicides or infanticides can only be understood by considering the perpetrator as someone fundamentally different to themselves. By blaming mental illness (despite the lack of evidence) as the cause of those crimes, some people may calm the anxiety that arises when people perceived that such cruel acts are performed by someone like them. Instead, this justification arises as a need to understand extreme cruelty and violence from the perceived abnormality.

Victim blaming in low profile femicides

and other VAWG manifestations

This sub-theme was heavily charged with victim-blaming content. For many of the readers, femicides (particularly low-profile news coverage) and other VAWG manifestations exist because women provoke them. The ways in which women precipitate this violence is by either their loose behaviour; or, because feminism is enraging the fury of men as they feel they are being scapegoated. While blaming victims is a common occurrence in many cases of gendered violence, the level of blame in the comments ranged from very subtle examples to the most extreme ones. For example, the following quote exemplifies a level of victim blaming that is subtle, yet very judgemental on one of the victims (the mother of the murdered girl)

Now the next step is to sterilise Fatima’s mother so she cannot leave anymore offspring. She can barely look after herself, how can she look after anyone else? (877-878)

The level of blame was also perceived to be direct or indirect in which direct would be the women’s actions causing VAGW or indirect, in which it will be the omission of women when adhering to stereotyped gendered roles what caused the violence.

An indirect example of victim-blaming is when some of the readers attributed the femicide of victims because their behaviour precipitated their victimisation. For example, the following two comments note that victims were murdered as they prioritised fun and going out over being at home for their own safety. For example, the following comments:

I think and I’m sorry to say but…this would have never happened if they (victims of femicide) had stayed at home, nothing good results when going out in certain places (1434-1435).

Yes, but it wasn´t time (to go out), they asked for it (victims of femicide) as simple as that and the mother (one of the victims) pretending to be a young woman. Please that’s non-sense, get a grip, you are old enough to understand that everyone gets what they were looking for (1481-1483).

These comments show that when people are confronted with news of gendered violence in Mexico in the current context, they need to find explanations as to why the violence occurs. A recurrent explanation is to place responsibility in the victims, particularly when they do not adhere to traditional gender roles (being submissive, not having fun, not going to parties, staying at home, adopting a mother role who does not have fun outside their home). This way of processing the news seems to suit a narrative in which rather than blaming the violence on the gender inequality; such explanations seek to perpetuate stereotypical gender roles and a submissive attitude from women and girls.

VAWG caused by a broken society

This sub-theme reflected those comments that considered that the expressions of VAWG are rooted in a society with either low levels of education or that is morally broken. Commenters used words to describe a decadent society such as “rotten”, “lost", "libertine”. This sub-theme is interesting because the ideas of a decadent society seemed to be heavily influenced by patriarchal and misogynistic ideas. The low levels of morality perceived used a conservative and patriarchal rhetoric in which the society’s decadence is the result of the loss of traditional and stereotypical gender values. The following quote implies that the society is in decadence because women are going outside their female traditional roles, hence losing the family values. In the following example, the victim of femicide was considered to have lost her values as a mother because she took her daughter to a party, and they were as mother and daughter to the mentioned party:

Dancing “without malice” what a way to call the lack of values and common sense. These women were murdered because the mother of the girl was a party woman, she even wanted to party at the horrible area of Ecatepec. This could have been prevented if the mother taught her girl some basic values, but the party was fun eh? (2302-2305)

These views are interpreted as the acknowledgement of mothers as the basis for moral values transmission. It also states that habitants of marginalised areas with high levels of deprivation should not go out and have fun because they promote the loss of values and put their offspring at risk of murder. In this regard, poverty, marginalisation and low levels of education, were also considered causes of a broken society at the next quote exemplifies:

The cause of all of this is the low level of Mexican society, how could we have first class politics and or police if the society is of a low class? The highest education degree of Mexican people is secondary school, how could we have police that have gone through higher education? (145-148)

This subtheme seems to highlight again a need to understand the acts of violence against women and girls in which holding on to conservative and traditionalist values seem to be the solution that many readers found to prevent the violence. What is interesting about this subtheme is that while there is an element of victim-blaming, it is quite clear that in this case women are not only considered responsible for the crimes perpetrated directly against them (victim-blaming), but in this case, their behaviour when separated from conservative gender roles is considered to be responsible for the degradation of the whole society.

Denial of VAWG. A matter of blame.

This

theme is concerned with expressions and sentiment in which many commenters denied

the existence of violence affecting particularly at women and girls, or that

considered that any violence in which women and girls are affected is just the

result of the generalised violence in the country. In this theme there are also

expressions that mock and disregard the feminist movements that ask for an end

of the VAGW.

Denial of the gendered violence

This subtheme conveys the perceptions which minimised VAWG by considering any acts of violence regardless of gender and part of a generalised violence in the country. These arguments seek to defend the idea that women are not at bigger risk of being victimised than any men. For example, the next comment:

“Divide et impera” Divide and rule, instead of media siding with the population exposing the corruption and negligence from local governments, they prefer to say “Femicide” “Gender alert” so women and man start fighting instead of getting united to combat the real enemy that both men and women have (2221-2224)

It seems to be that these comments tend to minimise VAWG and accuse those who denounce it as being exaggerated, impartial or favouring women, or even further trying to put men at disadvantage. It was interesting to note that these comments came from both male and female readers (deducting the gender from their usernames). For example, the following:

So now every murder against a woman is wrongly named femicide, did he just kill her for being a woman? If not, then is stupid to call this a femicide. What it is clear is that the society is more damaged everyday (126-128)

I am a woman and I support you there are also abused men who are murdered by crazy women (1632).

Violence is

not gendered, but women need to be more careful.

This sub-theme covers the comments in which readers considered that the violence endured by girls and women is not because of women’s gender making them a target; but because of their lack of care when accepting that as women they need to be more vigilant, more careful and less free than men to minimise their risks. In this case, gender is not acknowledged as a factor of vulnerability, but as a factor of inferiority. For example. The following reader notes that both genders are suffering the current violence in the country and as such women should be more careful than men because even them being men are still vigilant of their own safety.

If they are single mothers [victims of disappearance] why did they go out partying leaving their children with their mothers? Both women and men are fed up with so many femicides …but seriously women don’t take the mic! How the hell you go out partying with friends, leaving your children to your parents, they already looked after you and then you jump into a stranger´s car. Just because someone (because the perpetrator could be a man or woman) asked you to continue drinking. SERIOUSLY STOP TAKING THE MIC, NOT EVEN US MEN DO THAT! (2236-2243)

These types of comments seek to perpetuate an idea that women are in some sort of natural disadvantage in front of men and that if even they must remain vigilant, women should do so even more just because of their gender. These beliefs, hence, perpetuate patriarchal ideas of submission for women and considers them as socially incompetent when compared to men. In this dialogue it is believed that women should acknowledge their biological lower category and behave in consequence. This sub-theme reflects that for some people it is normalised and accepted a structural dynamic which restricts the freedom of women in relation to men as the following comment notes

Let´s see if you start understanding now, the times have changed. It´s not like in the past that you went to the shop and came back safe because nothing happened, now if you go walking on the street they will kidnap you or kill you. People nowadays are mentally ill, come on women get it, if you want to have fun there are times and adequate places (1347-1350).

It is concluded that this sub-theme differs from just victim-blaming as in this case there is both a denial of the gendered nature of the violence as women being targets, but as women precipitating the violence not just because of their actions but also their omissions and lack of acceptance of women’s inferiority.

Never mind VAWG, It’s your

politician’s fault.

This sub-theme reflected that for many of the news commenters, VAWG in Mexico is rooted in poor government policies, lack of government care and even an exaggeration used as a political strategy. This theme although not expected was surprisingly one of the most prominent themes among readers’ comments. It reflected some of the polarisation in the society in which people considered that the issue was responsibility exclusively of the government either local, federal, current, or prior seeming to do this as a blaming strategy in which the seriousness of the problem is minimised and understood as a political strategy to attack or defend political ideologies.

For some readers the current government is indifferent and is turning a blind eye to the VAGW. For many readers, particularly those who feel animosity towards the current federal government, the president is more concerned with his image than on admitting the seriousness of the problem and showing a willingness to work on a strategy that fights VAWG. For example, the following reader expressed how the government is more concerned with protecting its own power than attending gendered violence:

Women are not a priority for this screwed elder [The president], his priority is his army, soldiers, and marines, so when we want to take him out of power, they will defend him (202-204)

For an important number of readers governments actions or the lack of them was sending a message of impunity not only for femicides and perpetrators of VAWG, but for criminals in general. Hence, commenters considered that a criminal justice system with a focus on human rights is not a good government strategy to tackle VAWG. However, it was also noticed that for some readers the topic seemed to be more of an excuse to attack the current president and its government than a genuine concern about the issue. Comments on news as an opportunity to express political views and discontent was not exclusive to the current federal government and the president. Similar expressions of discontent and disapproval, but even of support for the government were displayed for different levels and jurisdictions of government. This reflects a social division about the perceived responsibility and management of the different layers of government and their strategies or influences towards VAWG. In contrast to those attacking the government, there was an important number of comments who seemed to be more interested in showing support or sympathy towards the federal government and aimed to point out that regardless of attacks about the government inaction to tackle VAWG, the current federal government is trying its best to solve the violence. These types of comments tried to emphasise that the federal government is trying to solve the problem who started in previous federal administrations.

Today a single man is doing what in 90 years your lords of the PRIAN [previous governments] did not do. They spent decades destroying the country and now you expect AMLO [current president] to fix this in a year (1935-1937)

It can be seen that for many of the commenters, the violence to which the victims were subjected came as a secondary topic. Hence, the topic was rather used as an opportunity to attack or defend the current, previous federal and local administrations. This is interpreted as societal expression in which despite women and girls are experiencing extreme levels of violence, for many, this is secondary, and it is more important to make this a political issue rather than to focus on the government strategies to tackle the problem and seek for a solution.

Resisting abuse as an invitation for abuse

This

theme englobes al the expressions in which the comments sections of the online

news were used to either reinforce sexist ideas, attack feminists’

manifestations and/or make fun of women or feminists in general. The

expressions in this theme are varied and go from sexist insults to female

commenters to the use of dark humour to refer to feminist movement and even

threats of sexual violence and even death.

Feminists are

crazy and creating unnecessary violence.

For many readers it was considered that feminists complain about violence, when they are violent in their protests so they we considered a hypocritical and of having double-standards. For others, feminists are women disconnected from reality that just want to generate disruption and violence as an expression of unmet needs, for example, male attention. While for some readers VAWG is real and an important issue, they considered that the feminist movement rather than help to create visibility of the problem they only make the problem bigger. For example, the following comments:

I will give you and advice girl, calm down because you will awaken real machismo and there will be men that will shoot at women and rape them and no one will support you, that is not machismo is the reality, you the feminists are creating a war between genders and not awareness (1808-1810).

You are just a bunch of cunts (to the feminists) you say it is not your intention, but you are calling all men rapists. Then do not complain when you receive what you deserve (1865-1866).

These comments derived from news which covered feminists’ protests. Some of the protests included a performance call “El violador eres tu” or “The rapist is you” (Annex B for lyrics). It can be noted from the quotes given that for some of the readers of these news the women protesting for justice against the rising number of femicides are considered as irrational. They are also accused of causing division between genders and to consider all men as rapists. For example:

Your feminist song calls all men as rapists, you are the crazy, damn feminazis note even the islamists are as extreme as all of you (1818-1819).

Nevertheless, the song that is referred to in the comments refers to a patriarchal criminal justice system that fails to convict men that have committed gendered violence, yet for some of the readers, the song is against all men.

Mocking

feminism with sexism

For many of the readers including men and women, feminists protests that demand an end to VAWG are just an exaggeration and a way for women to try to get attention and make unjustified accusations to innocent men. It was noted that a way to attack some of the comments aiming to present a case to recognise the problem of VAWG was to attack the persons who posted those comments by labelling of “feminists” “feminazis” and using derogatory comments about women and feminist women in general. For example,

Shut up femiwhore you only make me laugh (1782-1783)

These women only go to the protests and attack private property because they are cowards. These fat ugly women only want to attract attention because no one want to “make them the favour” (have sex with them) (1643-1644)

It was noted that when a person was trying to educate about the nature and content of the protests either physical or musical, they were soon targeted mocked and attacked by readers with insults such as crazy, fat or ugly. Some attacks had a sexual connotation in which women are non-deserving of male attention by their assumed physical appearance, crazy, fat, ugly. Or where they are called whores, or desperate for male attention.

3.3 Using sexist language to silence others online.

In most of the comments sections of the news selected, it was noted that a way in which commenters would attack each other when in disagreement would be trough sexist comments. It was interesting that while women will be directly attacked with comments about their person or body, male will be attacked through insulting their mothers, or their sexuality assuming homosexuality. For example, the following comments:

How about we ask your whore mother to come and open well her legs? (67-68)

Shut up and make me a sandwich (1785)

You are showing your “putarrraco” (bend) side. Clam down dolly (1940)

This subtheme reflects that sexist language in detriment of women is a common attack which targets women’s sexuality and stereotyped roles is used mostly by men in an attempt to denigrate or humiliate another person male or female. However, while women are directly targeted, so they will be the one mocked for her sexuality or stereotyped gender role (make a sandwich), the attacks to men will be about their female relatives (mother, sister, daughters), or an alleged homosexual orientation.

Discussion

The present investigation was concerned with understanding societal perceptions of VAWG through online discussions in the comments sections of different online news outlets. The findings of this study suggest that readers need to justify or understand why VAWG occurs. However, the appraisal of the reasons behind VAWG will depend on two main aspects, the first being the cruelty of VAWG manifestations, and second, whether the case was low or high profile as per news coverage. Where high profile would involve constant coverage of these acts as well as the sharing of many details implicated of the case such as name of those involved, background and in general a wider coverage. It is concluded that when readers faced high profile and high cruelty news, they tended to understand the attacker from a mental illness perspective; whereas in cases perceived as low profile and with less cruelty descriptions involved, readers tended to either a) blame the victims, b) deny the violence, or c) consider VAWG as a side effect of the generalised violence in the area. It is also concluded that VAWG as a topic can be used as a political agenda or as a form to mock/attack feminism and women.

When readers encountered news of high profile and high cruelty cases, these were commented with shock, sadness, anger and even surprise. While sadness and anger seem to be consistent reactions to this type of news, the element of surprise does not seem to match the seriousness of VAGW in Mexico. These reactions could suggest that people are not fully aware of the extent of VAGW in Mexico since these cases still surprise them. This is in line with Amnesty International’s (2021) findings that the real perpetration scale of VAGW is considerably higher than the one reported by authorities. Hence if authorities have an incomplete picture, the societal perceptions might be affected in consequence thinking that the seriousness of VAWG is less than the actual one. Another reaction in front of high cruelty high profile news of VAWG was the otherisation of perpetrators. Readers seemed to show coping strategies to assimilate VAWG news by distancing themselves and their environments and finding explanations for perpetration in drug abuse, mental illness, or trauma. This might reflect that despite some evidence of desensitization when confronted with misogynistic violence (, some readers still need to make sense of crimes that impress the society by either the level of cruelty or detail known about either victims or perpetrators. As suggested by Ricoy & Medina (2022) this suggests that there is a denial to accept such violence as part of the societal and structural structures.

Regarding the conversation around other manifestations of VAWG of low to medium profile cases, many readers seemed to made sense of VAWG as just another expression of the extreme violence that the whole society (men and women) are experiencing. It was interesting to see that some of the readers either denied the existence of VAWG completely, or if they acknowledged the gender factor, this was more as considering women to be more exposed due to their reckless behaviour. In other words, VAWG only happens to careless women and not women in general. These findings confirmed Ramos-Lira (2016) observations that in Latin America VAWG is understood as a side effect of the generalised and cartel violence in the region, rather than a problem on its own based on gender inequalities. For many readers, the hypersexualised forms of violence directed at women are not enough to convince them of the existence of a problem rooted in gender inequalities and this is manifested in a predominance of victim-blaming comments that perpetuate stereotyped ideas regarding gender roles (Agoff et al, 2007; Htun & Jensenius, 2022). A great number of commenters directly or indirectly blamed the victims, particularly when they failed to comply with traditional roles of submission and subordination highlighted as virtues of a good woman, mother, or girl. It is by the break of these roles when they precipitate their victimization.

The findings in this study also reflected that the topic of VAWG is a highly politicised one that people will use as an excuse to defend their personal beliefs, agendas. For example, for some people will be an excuse to defend or attack the political party of their affiliation/dislike. Other political use to the topic will be to either discuss the topic from a feminist perspective, or the opposite to spread sexist and even misogynistic beliefs, sometimes overt, but some other times hidden as humour. While there was no evidence of manosphere type of organisation in the comments and online conversations, this could have been due to the moderation practices. However, it was noticed that ironically sexist and misogynistic language was used to attack people with whom some of the readers disagreed. These comments included references about the sexual behaviour of women commenters, or if they were male, about their female relatives or assumed homosexual orientation. These behaviours are consistent with Jane’s (2015) concept of gendered cyberbullying. It was also noted that for commenters who somehow endorsed feminist ideas, explanations, these were attacked and discredited again with sexist or misogynistic comments, jokes, or open insults. All these behaviours are consistent with the literature that shows how patriarchal ideas are shared and perpetuated in online spaces as a perceived resistance to a threatening feminism (Ging, 2019).

Limitations

Getting an accurate picture of societal perspectives of VAWG from the comment sections of online news is challenging given that many factors could influence the perceptions and comments from readers. In first place, it could be that the way and amount of information that the media releases influence how readers make sense of the news. As it has been well documented, media outlets have a political affiliation which might use these topics as a strategy to influence perceptions of the government either positively or negatively. Hence, this having a direct influence in the comments provided by readers that give the impression of the topic being minimised and used to defend/attack political agendas. Secondly, the moderation of comments might also mean that some people do not write freely their thoughts for fear of having their comments deleted. This might also mean that comments charged with more misogyny could be deleted, hence biasing the comments analysed. When analysing the dataset, it could be seen that several comments were deleted by moderators in the different platforms. Thirdly, there is also the possibility of trolling behaviours, in which people write things they do not really with an aim to gain attention over the internet. Finally, it is unclear which demographics are more prone to comment on these outlets, and how this represents most of the sectors in society. All these reasons make it challenging to establish that the comments verted online are an exact an accurate representation of societal perspectives about VAWG.

Given these limitations, future research could complement or verify the findings of this study with participants both from qualitative and quantitative methodologies. From a quantitative methodology, it would be interesting to determine the demographic factors that predict condoning gendered violence and patriarchal beliefs. From a qualitative perspective, it would be helpful to understand in depth how people make sense of the news they are presented with based on their understanding of the victims, the perpetrators and the society in which they are embedded. Looking into data form moderated comments would prove particularly helpful to capture the extent of what is censored, but methodologically speaking this might be very challenging in terms of access.

Conclusions

The

findings from the present study show that VAWG is a topic that impacts and

worries society when the news coverage gives constant attention to the cases;

provides extensive information about the victim; it is perceived that there was

an excess of cruelty in the crime, or when the victim is considered as

faultless, particularly due to age. Nevertheless, the results of this study

also show that when VAWG is covered by news in which not much information is

given about victims, the description of crimes/events are more factual (i.e murdered, disappeared, battered, protest) society

tended to normalise the violence and find many reasons as to why it occurs.

Explanations ranged from victim-blaming to the weaponisation

of the topic as a political strategy, there was also considerable evidence of

denial of VAWG. The language used by many users when seeming to disagree with

other would ironically be charged with sexist and even misogynistic tones,

showing that VAWG is ingrained in society more than it might be acknowledged.

The implications of the present study point at the need for further education

in society, particularly in basic education about recognising VAWG. It would

also be suggested that politicians discuss how can awareness improved in the

society to tackle VAWG with initial steps such as recognition of the problem.

References

Agoff, C., Herrera, C., & Castro, R. (2007). The weakness of family ties and their perpetuating effects on gender violence: A qualitative study in Mexico. Violence against women, 13(11), 1206-1220. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780120730780.

Amnesty International. (2017, November 20). Amnesty Reveals Alarming Impact of Online Abuse Against Women. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/11/amnesty-reveals-alarming-impact-of-online-abuse-against-women/.

Baele, S. J., Brace, L., & Coan, T. G. (2021). From “Incel” to “Saint”: Analyzing the violent worldview behind the 2018 Toronto attack. Terrorism and Political Violence, 33(8), 1667-1691. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2019.1638256

Cantor D. J. (2014). The new wave: Forced displacement caused by organized crime in Central America and Mexico. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 33(3), 34–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdu008

Casey, E. A., Carlson, J., Fraguela-Rios, C., Kimball, E., Neugut, T. B., Tolman, R. M., & Edleson, J. L. (2013). Context, challenges, and tensions in global efforts to engage men in the prevention of violence against women: An ecological analysis. Men and masculinities, 16(2), 228-251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X12472

Data Cívica (2019). Claves para entender y prevenir el asesinato de mujeres en México. Retrieved from https://datacivica.org/assets/pdf/claves-para-entender-y-prevenir-los-asesinatos-de-mujeres-en-mexico.pdf.

Díaz, P. C., & Valji, N. (2019). Symbiosis of misogyny and violent extremism: New understandings and Policy implications. Journal of International Affairs, 72(2), 37–56. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26760831

Dragiewicz, M., Burgess, J., Matamoros-Fernández, A., Salter, M., Suzor, N. P., Woodlock, D., & Harris, B. (2018). Technology facilitated coercive control: Domestic violence and the competing roles of digital media platforms. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 609-625. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1447341

ENDIREH (2019). Encuesta Nacional sobre la Dinámica de las Relaciones en los Hogares. INEGI. Retrieved from https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/endireh/2016/

Ging, D. (2019). Alphas, betas, and incels: Theorizing the masculinities of the manosphere. Men and Masculinities, 22(4), 638-657. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X177064

Ging, D., & Siapera, E. (Eds.). (2019). Gender hate online: Understanding the New Anti-feminism (pp. 45-67). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gosse, C. (2021). “Not the Real World”: Exploring Experiences of Online Abuse, Digital Dualism, and Ontological Labor. In The Emerald International Handbook of Technology-Facilitated Violence and Abuse. Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83982-848-520211003

Gosse, C., Veletsianos, G., Hodson, J., Houlden, S., Dousay, T. A., Lowenthal, P. R., & Hall, N. (2021). The hidden costs of connectivity: nature and effects of scholars’ online harassment. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(3), 264-280. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1878218

Harmer, E., & Lewis, S. (2022). Disbelief and counter-voices: a thematic analysis of online reader comments about sexual harassment and sexual violence against women. Information, Communication & Society, 25(2), 199-216. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1770832

Heise, L. L. (1998). Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence against women, 4(3), 262-290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801298004003002.

Hoffman, B., Ware, J., & Shapiro, E. (2020). Assessing the threat of incel violence. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 43(7), 565-587. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1751459

INEGI (2019) “estadísticas a propósito del día internacional de la eliminación de le violencia contra la mujer (25 Nov ) Datos nacionales Retrieved from inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/aproposito/2019/Violencia2019_Nal.pdf

Jane, E. A. (2017). Gendered cyberhate, victim-blaming, and why the internet is more like driving a car on a road than being naked in the snow. In Cybercrime and its victims (pp. 61-78). Routledge.

López Ricoy, A., Andrews, A., & Medina, A. (2022). Exit as care: How motherhood mediates women’s exodus from violence in Mexico and Central America. Violence against women, 28(1), 211-231. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012219928

Menjívar, C., & Abrego, L. (2012). Legal violence: Immigration law and the lives of Central American immigrants. American journal of sociology, 117(5), 000-000. https://doi.org/10.1086/663575

Menjívar, C., & Walsh, S. (2017). The Architecture of Feminicide: The State, Inequalities, and Everyday Gender Violence in Honduras. Latin American Research Review, 52(2), 221-240. https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.73

Prieto-Carrón, M., Thomson, M., & Macdonald, M. (2007). No more killings! Women respond to femicides in Central America. Gender & Development, 15(1), 25-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070601178849

Ramos Lira, L., Saucedo González, I., & Saltijeral Méndez, M. T. (2016). Crimen organizado y violencia contra las mujeres: discurso oficial y percepción ciudadana. Revista mexicana de sociología, 78(4), 655-684. ISSN 2594-0651.

Regehr, K. (2022). In(cel)doctrination: How technologically facilitated misogyny moves violence off screens and on to streets. New Media & Society, 24(1), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820959

Secretaria de Seguridad y Protección Ciudadana (2022). Información sobre violencia contra las mujeres. Incidencia delictiva y llamadas de emergencia 9-1-1. Centro Nacional de Información (30/09/22). Retrieved from https://www.gob.mx/sesnsp/acciones-y-programas/incidencia-delictiva-299891?state=published

Soria-Escalante, H., Alday-Santiago, A., Alday-Santiago, E., Limón-Rodríguez, N., Manzanares-Melendres, P., & Tena-Castro, A. (2022). “We All Get Raped”: Sexual Violence Against Latin American Women in Migratory Transit in Mexico. Violence against women, 28(5), 1259-1281. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780122110139

Tekkas Kerman, K., & Betrus, P. (2020). Violence against women in Turkey: A social ecological framework of determinants and prevention strategies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(3), 510-526. 10.1177/1524838018781104

Tranchese, A., & Sugiura, L. (2021). “I Don’t Hate All Women, Just Those Stuck-Up Bitches”: How Incels and Mainstream Pornography Speak the Same Extreme Language of Misogyny. Violence Against Women, 27(14), 2709–2734. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801221996453