Four essential elements provide the support that justifies these lines. Four elements that, continuously, jump the fence of their own limitations. The words “genre”, “destiny”, “Greek tragedy” and “Colombia” serve as a starting point for a long journey seeking to articulate the ancient Western world with the cultural present of a South American nation that seems to be constantly on fire.

But the necessary ambiguity that has settled over the representative arts in the new millennium obliges us to offer a series of precisions regarding the meaning currently ascribed to these categories. First of all, it should be taken into account that my reflections focus, first and foremost, on the theater world. And that when we speak of “genre”, we refer to a term affected by that “confusion of terms” which, at the time, Patrice Pavis (1987) invoked in his explanation of the concept, in the now famous Dictionnaire du Théâtre1 Theatrical genres have been seen, well into the great ruptures of the twentieth century, as a set of differentiable typologies, whose form is determined by the resources of the word and, ultimately, tied to a type of literary decoding, where a vision of the theatrical is conditioned by a perspective rooted in the dramatic; in other words, in the dramatic text. In this verbal landscape, tragedy would then be one of an entire cast of generic stars, whose on-stage companions would be comedy, tragicomedy, farce, didactic theater, drama (or the play), and melodrama. And, returning to Pavis, dramatic genres cannot always be viewed from the perspective of historical evolution, but instead from their own poetics, and according to this logic, literary theory “préfère réfléchir sur les moyens d’établir une typologie des discours, en déduisant ceux-ci d’une théorie générale du fait linguistique et littéraire.”

When speaking of genre, therefore, we are speaking of a set of clearly differentiable conventions and norms that, in the end, are altered by the very works that represent them. The tragic genre is no exception. In the fourth century AD, Aristotle’s Poetics established certain rules, but with the frantic passage of time it would seem that the thick marble columns that supported these rules have cracked relentlessly and crumbled to the point of disappearing. But this necessary disaster has affected other genres besides tragedy. Beginning in the second half of the twentieth century, the theory of genres seems to have undergone a crisis. Or, at least, when studying theater, not from the perspective of the text but from the riddles of its representation, dramatic genres become more a set of exceptions or fusions ad libitum than a new typology of consolation for academic analysis.

Some ideas to develop: Romero (2015), Rivera (2001), Pavis (1987, p. 178.).2 3

The first question that I have raised revolves around an apparent paradox: if, to paraphrase George Steiner, “the tragedy (or rather, “the tragic genre, as understood by the Greeks”) is dead, “why have its characters, themes, fables, challenges, atrocious crimes, gods, and absences remained intact? To inscribe a dramatic text or a staging within the boundaries of a genre implies that said artistic experience is seeking a dialogue, whether consciously or otherwise, with other similar art forms. And yet, over the centuries, it seems that works such as The Suppliants, Electra or Iphigenia do not necessarily establish direct connections with the sources from which they have been drinking, and instead, this dialogue is often presented from the rearguard, not precisely through parody, but using the myths as points of eparture aimed, in most cases, not at a point of arrival but towards a vanishing point. In my doctoral thesis, I employed an eight-chapter structure based on the ancient tragedies (prologue, parode, stasimon, episode, exode), and a succession of “forking paths”, parodying the famous story by Jorge Luis Borges. My starting point was a reflection that established the difference between “tragedy” and “tragic”, from the perspective of genre, but including the specific exceptions belonging to the world of theater.

My research was, in the final analysis, guided more by the stage than by any direct referents from ancient texts.

The second element that interests me is the idea of destiny. The word destino, in Spanish, has a double meaning that indicates, on the one hand, a direction, a place towards which one in moving, and, on the other, the metaphysical connotation whereby human beings are subject to a variant of predestination in which their actions are determined by a script impossible to escape.

Destiny, in English, seems closely linked to the idea of tragedy, to the extent that certain definitions of the genre regard it as the struggle of men, titans, or gods to escape the inexorable laws to which they seem doomed to succumb. Are there no happy destinies in tragedy? The tragic genre and destiny are related; they are concepts united by an interjection that connects them in an indelible way and they would seem to require one another’s presence to feed their own internal definitions. In fact, the idea that unites them is tragedy and, in particular, Greek tragedy. Not Elizabethan tragedy, or seventeenth-century French tragedy, or political tragedy, or domestic tragedy. The idea of destiny or fate has unique characteristics in Greece (and, by extension, in Rome) and I approach its ineluctable laws knowing that, in the twenty-first century, we are certain to encounter new resistances.

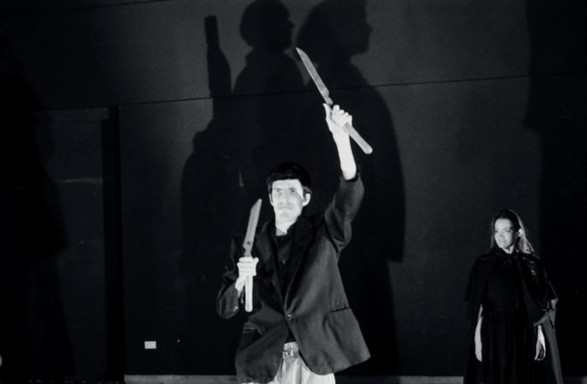

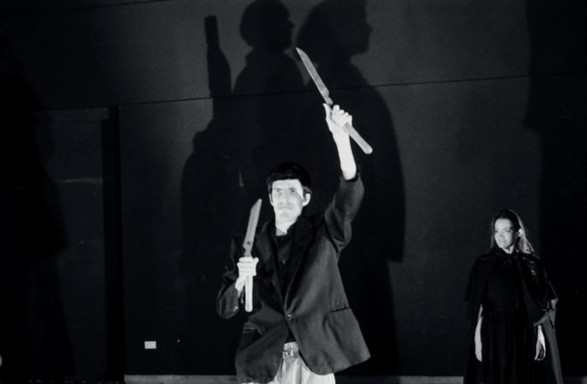

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

When speaking of the ancient tragedies, we must circumscribe to a specific period in the history of the theater when, between the years 480 and 400 AD, several pillars were established which, paradoxically, seem to have disappeared almost entirely, but whose ruins persist, deeply embedded, in different artistic and intellectual settings throughout the five continents. Greek tragedy became a genre and presented fate with a fatal challenge, so that its heroes have been fighting their own defeats for centuries, and have triumphed thanks to their respective failures. “Undoubtedly ... in times of crisis and renewal like this one, we feel a need to return to this initial form of the genre,” states Jacqueline de Romilly. She adds, referring to the scant 33 tragedies that have survived until today, “... because in them that reflection on Man shines with its primordial power” (De Romilly, 2011, p.9). But which “Man” is she speaking of? The man I am referring to is Colombian man, the 21st-century man who sees his excesses reflected in the concave mirror of the theater. We’ll speak of the Colombian man. In other words, the theater people who, in my country, have employed the Greek tragedy as their search engine. The Colombian, who, I might add, not only represents the Greek tragedies but, equally, is a witness (often an active witness) to them.

But why the Greek tragedy and not the tragedies of Shakespeare, or Racine, or Goethe, or Sartre, or Beckett? This requires pertinent clarification: the man who writes these lines has traipsed back and forth over the years, in and out of the fields of theater, cinema, literature, cultural journalism, radio, and television. For many years, a curious separation of “disciplines” existed, in particular between those who “tread the boards” and those who worked in the audiovisual world. (Lehmann, 2013, pp. 383-396).4 Although the boundaries between the so-called “visual arts”, “performing arts”, and audiovisual media began to disappear, there was a kind of distrust in Colombia among those who worked in direct relation with bodies (the officiators of the representative arts) with regard to the media arts. For many years, a kind of mistrust existed regarding those who used the media as a way of alienating the consciences of passive consumers and a symbolic barrier arose between “art” and “entertainment”.

Film producers and directors also considered themselves separate from their television homologues for the same reasons, while simultaneously claiming that the theater was unrelated to the “seventh art”, given its “artificiality”. Finding as I do, based on careful consideration, that the misunderstanding is valid, I set out to discover, in the very roots of the representative arts, the ways in which opposite forces tend, nevertheless, to find meeting points. This led me to write, in 1992, —thus completing my DEA (Diplôme d’Études Approfondies d’Esthétique, Sciences et Technologie des Arts) from the Université de Paris VIII, as part of the Arts, Philosophie et Esthétique Formation Théâtre program—, the study entitled L’Objectif et le Masque: La Tragédie Grecque à l’écran (Romero, 1992), in which I made my way through every film produced to date based on a Greek tragedy. Although, on the one hand, it was thought (and it is thought) that Greek tragedies can no longer be represented in their “pure state”, and, on the other hand, people claim that theater projected on a screen tends to be a problematic (if not obsolete) language, I was attracted to the challenging idea of discovering how a handful of filmmakers relied on the texts of Aeschylus, Sophocles, or Euripides to project their stories through a camera. It was the first step in finding answers to the reasons why the world of ancient representation could trigger a discussion of contemporary problems (Pasolini, Cacoyannis, Cavani, Jancsó, Guthrie, Straub, Huillet, and later Jorge Alí Triana or Lars von Trier).

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

Let us go now to the fourth element. For many years, the best local avant-gardes of their times claimed that Colombian theater only came into existence, with its own true identity, during the second half of the twentieth century. Over the years, and thanks especially to the careful studies of historian Marina Lamus Obregón, this theory has been called into question. However, as far as the Greek tragedy is concerned, the arguments of the so-called “new theater” seem to be correct, to the extent that, prior to 1954, there was no clear evidence of it on the national stage. Thus, it could almost be said that the stagings of the works of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides were discovered, in a curious paradox, along with the new scenic languages, the Stanislavski method, the Theater of the Absurd, and the theories of Jerzy Grotowski. However, this apparent irony of fate has a raison d’être which, deep down, has become part of the body of the present annotations. In the 20th century, Greek tragedy became a powerful tool not only to reflect on the human condition, as Ms. de Romilly states, but also as a point of departure for the aesthetic ruptures of new forms of scenic representation. And, to complete this spectrum, the Greek tragedy has served as a metaphor in the face of great social injustice when the dismayed laments of Antigone, Prometheus or the Bacchantes are launched into the audience to confirm that this is not the best of all possible worlds. In Colombia, a country located in northern South America with a history of more than two centuries of conflict, where Spanish is spoken and the culture is a mixture of the country’s indigenous traditions and all the Western values and disasters, the Greek tragedy could not be said to have been a constant, but this same exceptional quality has rendered it a philosophical, political, and artistic tool with which to criticize the surrounding circumstances—”this irremediable disaster” as novelist Fernando Vallejo skeptically affirmed.

And so, “genre”, “destiny”, “Greek tragedy”, and “Colombia” comprise the first thematic axis for the present set of ideas. To this end, our journey begins with a reflection on the distinction between the concepts of “tragedy” and “tragic”, a subject that has lent itself to more than one misunderstanding. Careful reflection on the different stagings (or cinematic, performative, or literary re-visioning’s), rather than on the internal workings of the original tragedies, leads to the conclusion that each creation reinvents its own tragic universe, and what once was a genre can become, given contemporary ambiguities, a new sign of approximation of the fatality of the present.

Little research has been done regarding the Greek tragedy in Latin America and almost none on its presence in Colombia. Reflections on Greece from a contemporary perspective (that is, from the perspective of its staged resurrections) have for the most part been carried out in North America or Europe, and not on the southern continent. It is therefore important to uncover the pieces to be assembled in a puzzle yet to be designed. Let us, first of all, start with what we might call the “stages of death”, where I contemplate the place occupied by Greek tragedy in contemporary models of representation. Secondly, we’ll take a look at what could be referred to as “The Tragic Feast”, wherein we’ll shed light on the scope of the “tragic” in Colombian society, a world that has, for over 60 years, remained trapped in a spiral of disconcerting violence that has immersed an entire nation, an entire generation, and, of course, all our attitudes regarding artistic phenomena. Here, we’ll take a look at “the tragic in Colombian theater”. In other words, we’ll explore the irruption of the Greek tragedy as one of the mechanisms used to speak, through art, of a reality that appears, at times, inapprehensible.

Little by little, we’ll discover its increasingly specific elements. And thirdly, “The ritual and the representation”, which introduces the idea of the ceremonial within certain manifestations of the so-called postmodern theater, and how to tackle the search for a new idea of catharsis.

This leads us to our first example, culled not exactly from within the realm of theatrical experience. In this case (“The Greek tragedy as a metaphor of Colombian culture”), we’ll look at four concrete examples of how characters from the ancient dramas have shaped diverse models of non-theatrical artistic forms. Notable examples: 1) Jorge Alí Triana’s film, Edipo Alcalde (1996), based on a screenplay by Gabriel García Márquez; 2) the “myth” of suicidal writer Andrés Caicedo and his curious Lovecraftian relationship with Greek characters (in particular, Antigone, protagonist of Caicedo’s novel, Noche sin fortuna (1976), and the short story entitled—naturally—“Antigone” (1971); 3) the book of poems, Hijos del tiempo (1989), written by Colombian poet Raúl Gómez Jattin, a monster devoured by his own ghosts of the ancient stage, and; 4) video artist José Alejandro Restrepo’s installation titled, Orestíada (1989), in which the artist introduces new fusions of theater and other forms of representation and confrontation of reality.

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

And, moving into the specifically theatrical arena, the rules may be the same, but certain themes and models lose their precision, to the extent that common pursuits and attitudes may share a certain constancy in their mise en scène. We’ll take a look at three significant ways of representing tragedy in a country like Colombia: first, tragedy as a philosophical concept (horror of emptiness, tragedy as the antechamber of death); second, tragedy as a social disaster (which, in Colombia, appears to be a stigma), and; third, tragedy as theatrical writing (in other words, the persistence of tragedy as a dramatic genre). Of course, currently these three paths cross one another and even more so with theatrical processes in deconstruction, as is the case with the Colombian theater movement. It is, however, pertinent to establish the specificities of these three forms of representation to see how, on the distant horizon, they finally converge and nourish each other.

The constituent elements of the tragedy (catharsis, destiny, the characters, and the chorus, among others) undergo necessary metamorphoses that affect and determine their specific meanings in each and every staging of the Greek dramas and their local translations. In my country, the ancient tragedies have been staged close to 100 times. In each of them, ideas such as catharsis evolve or are simply ignored. A similar situation arises when establishing equivalences between the structure of the original texts and their particular translations or reinterpretations on the different spaces of representation. Here we can establish a comparison of how this sort of stylistic variation is repeated in the different cinematic adaptations of tragedies. And not only in Colombia.

Each of these stagings must therefore be undertaken as a process of onstage writing rather than direct dependency on the literary text (or its adaptations). We’ll consider three different models of representational translations of the tragedies. Firstly: The illustrative vision. The theater as museum. In this group are the works in which the production serves the text and the word is the axis of the representation. Secondly: The complementary vision. The theater as temple. These are productions in which the text is preserved, but the staging questions this fact. Here, the word impels the image, but rebels from it, despite maintaining its rhythms and essences. And, finally: The opposing view. The theater as playground. This takes into account experiences in which Greek tragedy is a conceptual or thematic starting point, but that do not respect the original verses or their fables. The Greek tragedy here is a distant referent with which to play, manipulated until it becomes a new pre/ text of the creation.

Examples abound in the Colombian theater, and each becomes a unique staging experience, in which the Greeks end up “our contemporaries”, to quote Jan Kott, and at the same time, a sort of time machine exists that allows the past to breathe through the needs of old metaphors in the readings of the present. From the Radiodifusora Nacional de Colombia (1954) to the Teatro Experimental de Cali (TEC) (1959/1965), from the Teatro La Candelaria (1970/2006) to the Teatro Libre de Bogotá (2000), from the Teatro Matacandelas (2000) to the Teatro La Hora 25 (2008/2009/2010/2011), from the Festival Iberoamericano de Teatro (1988 – 2014) to Mapa Teatro (1995/2001/2005), and, finally, from Omar Porras (1996) to Pawel Nowicki (1990-1999) and from Juan Carlos Moyano (2006/2007/2010) to the theater schools, each and every one a pertinent detailed example of the manner in which, when exploring the specific environments in which their artistic experiences developed, they were made aware of the Greek tragedies, and their own theatrical devices.

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

At the current crossroads in which Colombian society finds itself, following the signing of peace treaties between the armed insurgency and the State, when the right-wing opposition sharpens its weapons to prevent implementation of the treaties and civil society closes ranks to defend them, the theater must adapt to this tower of confusion and present, through poetry, the riddles of reality. Two specific visions can aid in the reinterpretation of the “tragic” in Colombia. First of all, that of Professor Marta Cecilia Vélez Saldarriaga whose painstakingly compiled volumes, Los hijos de la gran diosa (1999), Las vírgenes energúmenas (2004), and El errar del padre (2007) analyze the phenomenon of the violence in Colombia from the perspective of the great symbolic figures of the Greek tragedy. And, secondly, the work of sociologist Elsa Blair, in particular Muertes violentas: La teatralización del exceso (2005), which takes an ultimate look at the phenomenon of extreme crimes (massacres, murders, tortures, disappearances) from the interpretation of their signs of horror (a possible reading of their respective and fatal “stagings”). It would therefore seem that the most terrible events portrayed in the Greek tragedies have not only been represented on stage, but have actually manifested themselves in the heinous conflict afflicting contemporary Colombian society. Thanks to these insights on the horror, the pieces of the puzzle come together: the violence in Colombia, the ancient texts, the scenic interpretations, and finally, the abject moments of the human condition, all have a chance to stare each other in the face, to choose a mask, and unveil their lamentations or cries of rebellion.

A pertinent conclusion (which might have served as an avant-propos) in the first person: the origins of my passion for the Greek tragedy are lost inside my memory. The first children’s plays I enjoyed in life were at the Los Cristales open-air theater in Cali, Colombia, my hometown, a stage built on the slope of a hill, emulating the ancient Greek theaters. I have vague memories of the Teatro Escuela de Cali’s King Oedipus, enveloped in mists and entangled with images of black and white photos. I also treasure a discreet source of family pride based on the discovery that the oldest versions of two works by Aeschylus and Sophocles (Chained Prometheus and King Oedipus, respectively) were directed by an uncle of mine, a pioneer of Colombian theater, Bernardo Romero Lozano,5 which he directed for Colombian National Radio in 1954. Never did I, throughout my theater studies at the School of Fine Arts in Cali, act in or direct a Greek tragedy, except for technical choral exercises. It wasn’t until 1988, when I began teaching acting at the now defunct National School of Dramatic Art (ENAD) in Bogotá that I staged for the first time a work based on the old tragedies. It was not a single text, but rather a kind of funereal juxtaposition based on several specific myths.

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

With only four actors in my class, I decided to write a version titled, Fatum (fate, in spite of its Latin connotations, had already begun to knock on my door), composed of fragments of Aeschylus’ Chained Prometheus and Agamemnon, Sophocles’ King Oedipus and Antigone, and Euripides’ Medea and The Bacchantes, articulated by poetic texts rooted in ancient choruses. The staging was “in black and white and red”, the lighting favored amber and blue tones, and Arvo Pärt’s Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten provided musical support. Despite having studied the tragedies with due attention in my theater history classes, it was during this process that I truly discovered the profound philosophical, social, and scenic dimensions of the ancient myths; the contemporaneity of a theatrical text can only be measured at the moment when its verses, dialogues, or didactic nature (if such exists) enter into that territory of fascination and wisdom achieved only in the spaces conceived for representation. Years later, I repeated the experience in a co-production between the defunct Bogotá National School of Dramatic Art and the Nordisk Teater Skole of Arhus (Denmark), which presented a multicultural staging of Electra in which the limits of the spoken word (Spanish, Danish, Norwegian, Latin, English, and Greek) exploded to give way to profound dimensions of meaning, based on the poetic boundaries of the actor’s work.

Time, for all men, tends to slip away. And with it, the themes that color destiny. The great myths of the Greek tragedies and their fearful wisdom have stayed with me, and I see them reproduced in the subjects I study, in the works I stage, in my son’s video games, in the adventures of audiovisual media, in contemporary music, in opera, and in the experimental theater group, and a distinguished director of radio dramas and the landmark productions of the fledgling National Television of Colombia.

countless variations of pop culture and counterculture. The rewriting of tragedy continues steadfastly beyond its own limits and, with it, we illuminate the path of our artistic and personal uncertainties. My journey through Greek tragedy, apparently, is not over. Colombia would seem, however unintentionally, to imitate the ancient myths. It is the unusual and inimitable territory, in which I was born, the place where I live, and the land in which the gods, in all their bewildering wisdom, decided I was to assume the burden of a search, as the most difficult and stimulating of challenges.

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).

Electra. Coproducción de la Escuela Nacional de Arte Dramático (ENAD; Bogotá, Colombia) y la Nordisk Teaterskole de Arhus (Dinamarca). Dirección: Sandro Romero Rey. Fotos: Karen Lamassonne. (1993).