Abstract: The General e grand estoria (GGE), a universal history commissioned by King Alfonso X in the 13th century, is a uniquely vast and rich resource, bringing together Christian, Muslim, and Jewish sources, as well as apocryphal and Classical ones, translated into the newly-evolving Castilian language. We maintain that only a wide-ranging, international and interdisciplinary team can unlock the complexities of this enormous, multicultural text, and that digital tools are essential for managing this collaborative work. “The Confluence of Religious Cultures in Medieval History” is a collaborative project to digitize, edit, annotate, and translate the text. We set out how the project offers a new partnership model, suite of digital tools, and experiential learning opportunities for emerging digital humanists and scholars of Spanish, English, French, Arabic, and Hebrew, and explore the possibilities opened by the digital to advance a coordinated global program of training and knowledge mobilization.

Keywords: Medieval Iberia Cross-cultural collaboration, Digital Humanities, Translation, Universal histories, General e grand estoria.

Resumen: La General e grand estoria (GGE), historia universal encargada por el rey Alfonso X en el siglo XIII, es un recurso singularmente extenso y rico, que reúne fuentes cristianas, musulmanas y judías, así como apócrifas y clásicas, traducidas a la lengua castellano en pleno proceso de evolución. Creemos que, sólo un equipo suficientemente amplio, internacional e interdisciplinar puede revelar la complejidad de un texto de este tamaño y grado multicultural; para la gestión de este trabajo de colaboración las herramientas digitales son esenciales. “The Confluence of Religious Cultures in Medieval History” tiene como meta digitalizar, editar, anotar y traducir la GGE. En este artículo, expondremos cómo este proyecto ofrece un nuevo modelo de colaboración, nuevas herramientas digitales y oportunidades de aprendizaje experimental para las humanistas digitales y para especialistas en filología hispánica, inglesa, árabe, francesa y hebrea. Igualmente exponemos las posibilidades que el mundo digital ofrece para coordinar un programa global de formación y movilización del conocimiento.

Palabras clave: Iberia medieval, Colaboración intercultural, Humanidades Digitales, Traducción, Historias universales, General e grand estoria.

Resumo: A General e grand estoria (GGE), uma história universal encomendada pelo rei Afonso X no século XIII, é um recurso excepcionalmente vasto e rico, reunindo fontes cristãs, muçulmanas e judaicas, bem como fontes apócrifas e clássicas, traduzidas para o língua castelhana em evolução recente. Afirmamos que somente uma equipa abrangente, internacional e interdisciplinar pode revelar as complexidades deste enorme texto multicultural, e que as ferramentas digitais são essenciais para gerir este trabalho colaborativo. “The Confluence of Religious Cultures in Medieval History” é um projeto colaborativo para digitalizar, editar, anotar e traduzir o texto. Definimos como o projeto oferece um novo modelo de parceria, um conjunto de ferramentas digitais e oportunidades de aprendizagem experiencial para humanistas digitais emergentes e estudiosos de espanhol, inglês, francês, árabe e hebraico, e exploramos as possibilidades abertas pelo digital para avançar uma programa global coordenado de formação e mobilização de conhecimento.

Palavras-chave: Península Ibérica Medieval, Colaboração intercultural, Humanidades Digitais, Tradução, Histórias universais, General e grand estoria.

Dossier

Harnessing digital tools to unlock the complexities of the General e grand estoria

Emplear las herramientas digitales para revelar las complejidades de la General e grand estoria

Emplear as ferramientas digitais as complexidades da General e grande estoria

Received: 17 March 2024

Revised: 02 May 2024

Accepted: 20 June 2024

Can the desire for knowledge drive collaboration in spite of seemingly insurmountable religious differences? As in the present, the production of knowledge in the medieval period reflects both systemic inequities and profound attempts to bridge cultural understanding. 800 years ago, in Medieval Iberia, though there was conflict and power struggles between Muslims, Christians, and Jews, scholars from the three faiths worked side by side to translate and co-produce what became the foundations of knowledge systems in the modern academy. In southern Iberia and across the Mediterranean, a new information highway forged by trade and conflict fostered collaborations that drove innovation across the arts and sciences, from medicine and mathematics to theology, philosophy, and music.

“The Confluence of Religious Cultures in Medieval Historiography” project will revitalize the collaborative legacy of Medieval Iberian scholarship by fostering new pathways for translation, research, training, and memory work across the Mediterranean and around the world. In medieval texts, we can see early readers recognizing and grappling with tensions between Muslim, Jewish, and Christian sources as they interpreted the past and present. The modern, Western preference for a single dominant voice and the limitations of the printed book have erased this texture from our history by obscuring narratives that deviate from the mainstream. In the 13th Century, Medieval encyclopedism in the form of universal histories reflected a rise in curiosity that involved collaboration, translation, synthesis, analysis, and diplomacy. This project applies cross-disciplinary lenses and an innovative approach to digital collaboration focused on one such universal history, the General e grand estoria (GE). Commissioned by King Alfonso X of Spain (r. 1252-1284), this text was a state-sponsored initiative to synthesize information on a scale that had not before been possible. It unfolded in parallel with similar cultural initiatives to develop unified histories in China, Iran, India, and elsewhere.

The overarching goal of this project is to foster generative dialogues about that shared Muslim, Jewish, and Christian cultural heritage by challenging mainstream assumptions about how meaning is made and communicated. Our team includes over 40 scholars and practitioners and 11 partner organizations across Canada, Colombia, Egypt, Portugal, Spain, Tunisia, the USA, and the UK. We have a strong track record for innovation in the Digital Humanities demonstrated by COLABORA, the digital platform that we have developed with support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and other organizations over the past eight years. Using COLABORA, we have made previously out of reach sources accessible, piloted new ways of crowdsourcing scholarly analysis, and laid the groundwork to create the first-ever complete edition of the GGE. Our research team’s collaborative transcription, translation, analysis, and digitization of the GGE has enabled us to identify and analyze intersections between Jewish, Islamic, and Christian traditions. In addition, this project is breaking ground in the Digital Humanities through our use of artificial intelligence to prepare paleographical transcriptions of some sources and to aid in the process of translation. We will open up this robust research initiative to academic and community partners who have traditionally been excluded from dominant scholarly dialogues about their own cultural traditions.

In this article, we firstly present how digital humanities tools are essential for understanding a text as vast and rich as the GGE. Next, we offer a history of the project to date, our objectives and current working practices, highlighting how the digital allows for a wide-ranging, interdisciplinary collaboration between scholars across four continents. We set out how the project offers a new partnership model, suite of digital tools, and experiential learning opportunities for emerging digital humanists and scholars of Spanish, English, French, Arabic, and Hebrew. Finally, we explore the possibilities opened by the digital to advance a coordinated global program of training and knowledge mobilization.

The cultural moment of Medieval Iberia offers a window into pre-colonial approaches to meaning-making wherein multiple interpretations and ways of knowing from Muslim, Jewish, and Christian knowledge systems could coexist in the same texts. Writing history from a global perspective and the expressed desire of collecting the complete acquired knowledge, have been two intertwined practices in civilizations all around the world throughout history. In the 13th Century, a rise of global curiosity and encyclopedism spread, especially across the Mediterranean. This impulse to acquire universal and complete acquired knowledge, that today would be labeled as accumulation and rationalization of Big Data, reached its most significant peak before the Enlightenment between the 13th and mid-14th Centuries worldwide. A century before Rashid al-Din Hamadani (d. 1318) unified the history of the Mongols with the history of China, the Biblical and the Jewish people, pre-Islamic Iran, and the Indians and Mamluk Egypt, and Ibn Khaldum composed the last Medieval Arabic encyclopedia, the Castilian king Alfonso X undertook a cultural project of universalist ambition, unheard of in the medieval world. The Iberian Peninsula - both in al-Andalus and in the different Christian kingdoms - provided the cultural content as a foundation for social and religious identities expressed in, at least, four different languages: Hebrew, Arabic, Latin, and Castilian. While in other European countries the first testimonies of encyclopedism were produced in an ecclesiastical context and were written in Latin, in the Iberian Peninsula the creation of laborious compilations of knowledge and history involved Hebrew, Arabic and Castilian and far more secular surroundings. The Jews in Medieval Spain represented an essential intellectual bridge between the extensive knowledge written in Arabic and the Christian world. In the Iberian Peninsula, authors like Bar Hiyya (d. 1136), Ben Ezra (d. 1167) and later, by Shem-Tov Ben Falaquera (d. 1290) displayed in Hebrew a clear encyclopedic spirit. Alongside with the historiographic Arabic tradition developed in al-Andalus, all these works influenced greatly the distinctive universalism of the Alfonsine intellectual enterprise. In comparison with other histories written in Christian Europe, even when written in various vernacular languages, the monumental and multicultural dimension of Alfonso´s GGE was unparalleled.

Alfonso shared the universal idea of predecessors such as Eusebius, Jerome, and Petrus Comestor that history needed to be divided in two main blocks: the history of the Bible and the history of the gentiles. But he took this idea much further. For the first time, this universal history introduced Arabic sources (written by Muslim historians and geographers of al-Andalus) to expand the biblical canon and the canon of Greco-Latin authors (Lucan, Ovid, Pliny the Elder, Orosius, Paulus Diacoccus, etc.). The GGE brought into Castilian language and culture diverse religious and classical sources, including Christian, Jewish, Islamic, and—notably—apocryphal interpretations of the Bible, as well as accounts from the mythological and historiographical traditions from the classical Greek and Latin world. Its six extant volumes—the last of which was never completed—aimed to tell the history of the world from creation to Alfonso’s reign, though they only reached the New Testament before Alfonso died.

In the 13th century, the first steps were taken to transform Spanish into the standard and universal language that we know today. Through the composition of the GGE, the Castilian language was completely transformed by King Alfonso X. This work contributed enormously to the expansion and standardization of the Spanish language. The influence of Alfonso “el Sabio” on medieval Europe was particularly significant in the field of science. The translations of astrological and astronomical texts sponsored by the king represented an important chapter in the scientific history of the West. Some of these works were translated into other languages and their dissemination exceeded the limits of the Iberian Peninsula, becoming works of reference in Renaissance and Baroque Europe. Also, for the first time in the history of Europe, he promoted the writing of scientific works in Spanish, while in the rest of Europe Latin would be the only scientific language until well into the Modern Age. Thanks to all these texts, Spanish was enabled for the first time for the expression of mathematical calculations and technical processes. Through these texts, the Spanish language incorporated into its vocabulary scientific and technical terminology that did not exist in any other European language.

The decision to translate Arabic texts into Spanish throughout the GGE is another of the main novelties of this work in the European historiographical production of the 13th century. Furthermore, the method of translation is a milestone within the discipline itself, since Alfonso X ordered that work should always be done in pairs, in which a Jew who knew Arabic or even a Muslim (or a convert) would be in charge of translating the Arabic text into Spanish while a cleric who knew Latin would translate this text from Spanish into Latin. The great novelty introduced by Alfonso X with respect to other translations made in the Western Middle Ages (among which we should mention those of Archbishop Raimundo of Toledo) is that he gave value to Castilian as the target language, and not so much to Latin. His main aim was to tell the history of mankind in Castilian, hence the copying in the vernacular of the lavish royal codices that we still have today. On the other hand, more modest translations in Latin (especially of scientific texts) continued to be made, which would reach Europe and would have a decisive influence on later centuries.

At the same time as Alfonso X’s translations were prepared, Medieval Europe was living under the laws emanating from the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215, that precluded any Islamic or Jewish “contamination” of Christian religious communities and, therefore, texts. This period thus represents a before-and-after for religious, social, and cultural relations in Christendom. The decision to develop the GGE in the vernacular, Medieval Spanish, represented a step toward public accessibility as well as a political move by an institutional power to define what was true and control the circulation of information. While the text represents an unprecedented confluence of religious, cultural, and linguistic perspectives, it also captures many of the challenges and questions we face in the digital age. The GGE thus constitutes a major testimony to the complex and dynamic reality of medieval Iberia, and yet—until 2016, with the funding of our first SSHRC grant—its study had been restricted for the most part to philological approaches, and it had not been tackled from an interdisciplinary perspective.

Like many universal histories and other medieval texts, studies of the GGE have been fractured by the disciplinary silos of the modern academy and inequitable access to archives where manuscript witnesses are stored. A key element in Alfonso X’s cultural enterprise was his promotion of the vernacular Castilian language (Medieval Spanish) to the status of the literary and official language of his kingdom, breaking with the previous monopoly of Latin. The GGE was intended to cover all of human history, from the creation of the world to the king’s own reign. Although it was created under Christian hegemony, it is the product of a complex environment of both interreligious cooperation and suspicion.

Scholarship of medieval Iberia has insufficiently recognized the relevance of the use of non-Christian sources in the composition of historiographical works such as the GGE. Rico has held that Alfonsine historiography is part of a unitary project—both political and cultural—that links the work of the scriptoria of the GGE to a solely Christian tradition that follows the patterns of the works of Isidore de Sevilla, the Chronica Albeldense, and the French scriptoria.1 Assumptions that the GGE is a Christian text have limited research to the same methods used to study other historiographic works such as the Estoria de España, which does not incorporate Muslim and Jewish sources.

The incorporation of medieval Arabic chronicles in GGE is a key link between Islamic and Christian historiography. Alfonso considered himself the heir of a line of sovereigns that started in biblical times, with the wise king Solomon, and that stretched throughout Antiquity and the period of Islamic rule, until it reached its culmination in him. He incorporated Arabic chronicles in the GGE to fill gaps in periods before Christian rule to support his political legitimacy. There are few studies of Arabic sources in the GGE,2 and of Jewish sources such as rabbinic writings.3 While these studies have revealed valuable insights, there is still much to explore in terms of how Christian, Jewish, and Muslim sources intersect in the text.

There are limited critical editions and no full published translations of the GGE. In the 20th century, scholars were limited to partial critical editions.4 To address this gap, in the 1970s, the Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies published the paleographic transcriptions of most GGE manuscripts, first on microfiche and later with computer support.5 These transcriptions played a critical role in the distribution of the work among specialists. By the time Sánchez-Prieto Borja coordinated the full critical edition of the text in 2009, the enterprise of making the GGE accessible had become one of the earliest sites of innovation in the Digital Humanities. While the 2009 printed edition has been valuable to the study of medieval historiography, it is unable to capture the full complexity of the GGE. Among other limitations, the 2009 edition lacks explanatory notes that might identify sources or add cultural, religious, lexical, and linguistics details to aid in interpretation.

Emerging digital technologies make it possible to overcome many of the systemic barriers embedded in modern scholarship about the Middle Ages and catalyze research at a rate that was scarcely imaginable a few decades ago. Medievalists have been at the forefront of innovation in the Digital Humanities, experimenting with digital critical editions of texts such as Estoria de Espanna Digital or Boethius: De Consolatione Philosophiae. In the 1990s, scholars began to publish digital facsimile editions—Kevin Kiernan’s Electronic Beowulf,6 or Hoyt Duggan’s Piers Plowman.7 In the decades since, scholarly digital editions have become much more than mere “editions” in the traditional sense of the term. Digital editions have been characterized as “digital archives”,8 “information-rich transcription of documents”, and “digital documentary editions”.9 However, these major initiatives are limited to a select few medieval texts, and they have limited capabilities for readers’ interaction with the platform.

Our work builds on these previous efforts with our digital platform, COLABORA, which facilitates interdisciplinary collaboration and enables us to augment and expand the text with details and annotations that are impossible in printed editions. In the process of creating digital editions, the task of the editor is not so much focused on the production of a finished result, but rather on facilitating a creative engagement of the reader with the text. In doing so, the editor should also be aware of their own authority and responsibility in structuring and arranging the contents, and their guaranteeing accessibility, a wide-encompassing practice that has been termed “editorialization”, as opposed to “edition”.10 Robinson, in “Towards a Theory of Digital Editions”, argues that digital editions must represent both text-as-document—rich digital facsimiles of material artifacts, pages, manuscripts—and text-as-work—that is, “what it means, who wrote it, how it was distributed and received, how it is differently expressed”.11 With our normalizations, annotations, analyses, and digital tools, our annotated digital edition will enable readers to engage with both text-as-document and text-as-work. Moreover, our platform will, for the first time, provide translations of the GGE into English and French alongside the Spanish annotated text and digitized manuscript.

Due, in part, to the loss of cultural complexity in static GGE printed editions, scholars researching the text from diverse disciplinary perspectives have had limited success integrating their findings. One consequence of these limitations is that interpretations of cross-cultural sources tend to be myopic, biasing toward the conventions of predominant academic disciplines and excluding, for example, contemporary cultural and theological readings of texts in religious institutions and cultural foundations. Static printed texts are necessarily limited in their ability to capture the dynamics of translation, which are bedrock to understanding the flow of ideas in any medieval text. By facilitating cross-disciplinary collaboration, our team is generating an annotated digital edition that has already advanced new knowledge about the main linguistic, lexical, and historical issues in the GGE. Our global and cross-disciplinary approach will enable us to identify and link Muslim, Jewish, and Christian sources.

The idea of the project emerged from Peña Fernández’s exploration of the cycle of Adam and Eve in Spanish sources in preparation of a future monograph about Cain.12 The GGE is one of the few documentary testimonies of the apocryphal and pseudepigraphical biblical traditions of Christian sources in Medieval Iberia. Having already explored different Ancient and Medieval narratological rewritings of the first episodes of the Bible, the first glance of the same episodes in the GGE opened a complex and, at the same time, fascinating reality. It was not only due to the numerous echoes and intertextual references that were found, but also the originality in their narratological strategies. It was very clear that this was a book with far more than a single voice or a simple perspective and, undoubtedly, a single interpretation.

The level of complexity and uniqueness seemed to be asking for a non-traditional approach. This vast source required a multidisciplinary mindset and, therefore, a multidisciplinary team, bringing together specialists across Biblical sources, Arabic sources, Gentile sources, the history of the Spanish language, textual edition, archival research, and translation, among others. The second most obvious conclusion was that the support of digital technology would be essential to facilitate such interdisciplinary research and to manage and convey the complexity of the text.

The incredible work developed by the Biblias Hispánicas project under the direction of Claudio García Turza made them the first logical partner.13 With the support and enthusiasm of other colleagues from American, Canadian, and Spanish universities we committed to continue the work developed years earlier under the direction of Pedro Sánchez-Prieto Borja to unravel and promote the knowledge of the GGE. The first funding provided by SSHRC was in the form of an Insight Development Grant (IDG). This IDG enabled us to start building a multidisciplinary research team whose goal was confronting the challenges that have, in the past, prevented individual scholars from achieving a deep comprehension of the GGE. The project had three main objectives: to move towards understanding the GGE from a multidisciplinary perspective, to start developing an effective approach to collaborative work, and most importantly, to solve the digital challenges, such as the Part of Speech tagging and lemmatization of the text, the creation of a collaborative platform that could be simultaneously used by all of the different project teams. In the eighteen months, we explored a number of digital possibilities, contacting already-established research teams in Digital Humanities. Following a conference on Hispanic Bibles in Mallorca and another on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo in 2018, we entered into collaborative work with the Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies (HSMS) and began interconnecting our new project with their established and well-known digital projects. In the initial stages of the project we considered utilizing TEITOK, a web-based platform for viewing, creating, and editing textual corpora. However, despite its many functionalities, we soon discovered that TEITOK has limitations working with large text files, such as the GGE. In 2018, in order to create the textual basis of our digital platform, we started the conversion of the HSMS transcriptions of the GGE to XML format, using a set of XML tags that reflected the physical structure of the text (folio/column/line) and its characteristics (abbreviations, scribal interventions, etc.) and included lemma and morphological tags for each token.14 We also developed a set of criteria to automate the conversion of the paleographic transcriptions into a normalized edition, and finally the synchronization and XHTML parallel visualization of the digital facsimile with the paleographic and normalized versions.

In 2019, building on the foundations of the previous years, a second, larger SSHRC grant allowed us to begin composing a far more substantial and interdisciplinary team, with the addition of new institutional partners. At this point, we decided to include collaborative translation into English by student interns as a further way to explore the meanings of the text and to share it with a wider audience. In the same year, Javier Pueyo Mena designed and implemented COLABORA, our Digital Collaborative Platform, making use of the textual base developed previously and creating the initial collaborative modules (edition, annotation, translation, bibliographic, primary sources) that allowed our teams to work online, both synchronously and asynchronously, from different locations and time zones. From 2020 onwards, the edition, annotation, and translation modules of the platform were enriched with the integration of other digital resources (linguistic corpora [OSTA15], dictionaries [DPCAX16]) that made it possible to increase and accelerate our research productivity. The Bibliographic and Primary Sources modules were integrated with our Zotero bibliographical collection, integrating both platforms via the Zotero API. The use of Zotero ensures that all members of the team have access to our expansive, and growing, archive of sources to inform their work on the GGE. All of the modules in COLABORA are interconnected and changes made in the edition module are immediately reflected in all of the other ones, thus assuring that all teams are working on the same common text.

In 2023, we started to explore the use of real-time collaborative editing and communication in some of the modules, via the integration of our platform within a Nextcloud content management system. The COVID-19 pandemic not only proved that our innovative digital platform would allow us to develop an even more international, interdisciplinary, and collaborative work, but also forced us to develop creative means of working together remotely. Consequently, as the level of collaboration on publications has increased, the outputs from the project have grown at an exponential rate. In terms of geographical spread, the project has expanded organically as more partners have joined the project, reaching its most important and challenging space: the connection between southern Spain and North Africa.

Our collaborative study mirrors the practice of the medieval scholars working under Alfonso X. We seek to reveal the diversity and complexity of ideas, practices, and interactions among different religious communities and individuals that share a common, but at times separated, physical space. Through our digital platform, partnership network, and cross-disciplinary research design, we are working to surface cultural heritage that has been sidelined by making sources newly available to the public and foregrounding the voices of North African scholars in humanities scholarship. Our overarching goal is to foster generative dialogues about shared Muslim, Jewish, and Christian cultural heritage by challenging mainstream assumptions about how meaning is made and communicated. Leveraging COLABORA, we aim to make previously hidden sources accessible, catalyze collaborative translations of the GGE, and pilot new ways of crowdsourcing scholarly analysis. This ambitious project is guided by four objectives:

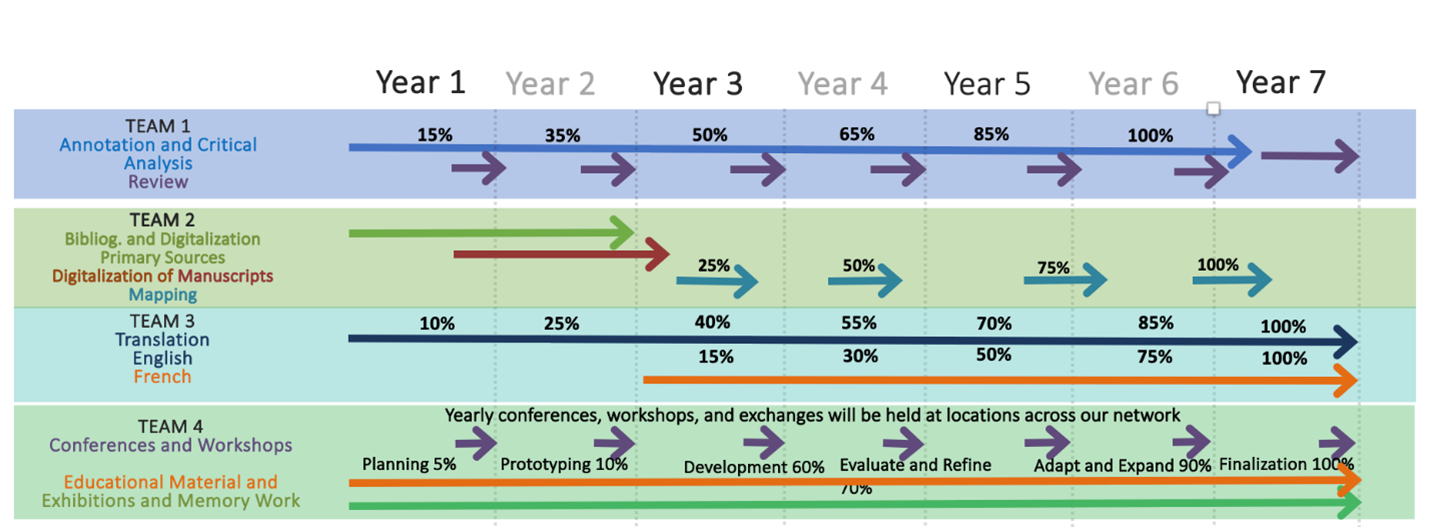

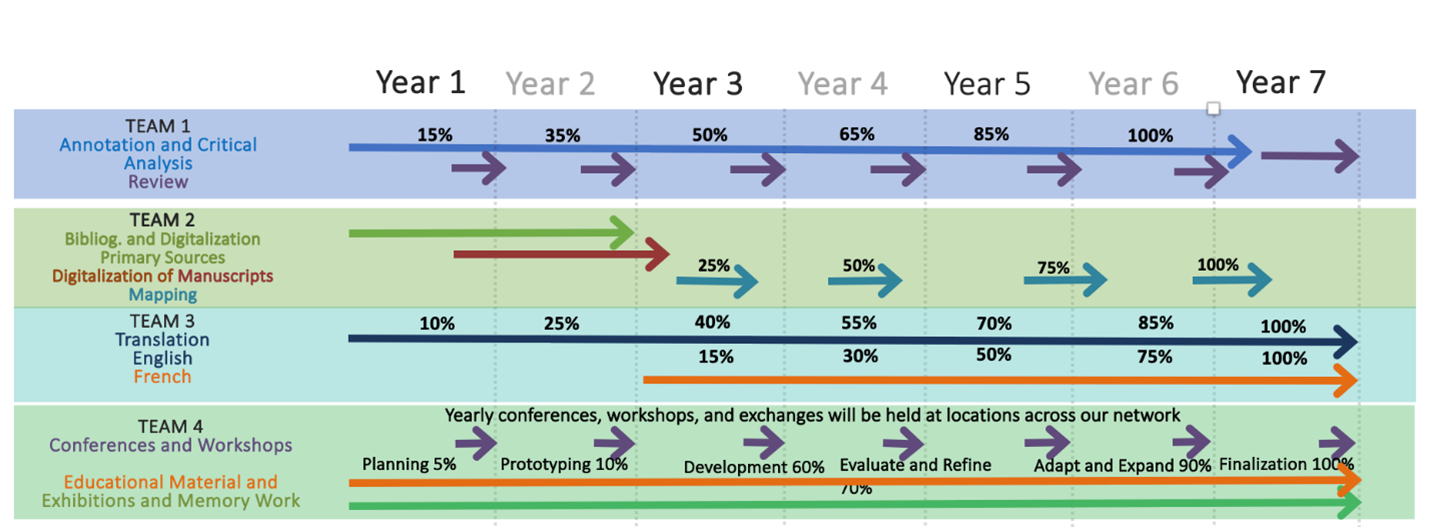

Given the length and complexity of the GGE, we plan to complete these goals over seven years, as depicted in Image 1.

The project revitalizes the confluence of Muslim, Christian and Jewish perspectives that existed in the Alfonsine period with scalable tools, strategic partnerships, and new collaborative spaces to include marginalized scholars and memory workers in the co-production of knowledge. It reconnects the information highway across the Mediterranean that existed in the thirteenth century, extending it to academic and non-academic partners in Canada, Colombia, Egypt, Portugal, Spain, Tunisia, the UK, and the USA. The geographic span of our team is indicative of our diverse lived experience and place-based knowledge, both critical forms of expertise for the project. We bring together the collective knowledge required to advance this ambitious project, including expertise in digital technologies, languages (including medieval and modern Spanish, Arabic, Hebrew, Latin, English, French, and multiple regional languages such as Aragonese, Leonese, and Provençal), advocacy, cultural heritage management, memory work, community engagement, and rigorous methodologies of history, textual analysis, archival studies, philology, bibliography, translation, and other fields across the humanities. This unique integration of expertise has enabled us to build our digital platform, COLABORA, and use it to recognize and preserve the complexity of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish voices in this medieval text. In turn, the digital platform allows for a streamlined approach to collaborative working, where each team can share resources and edit, annotate, or translate the text simultaneously.

Our project includes four teams: (1) Research Annotation and Edition, (2) Archive and Bibliography, (3) Translation, and (4) Digital Tools and Knowledge Mobilization. Many project members work across more than one team.

Team 1, “Research Annotation and Edition”, coordinates scholars working across five research streams who apply cross-disciplinary lenses to targeted dimensions of GGE scholarship. Team 1 aims to generate rigorous annotations to show where the GGE connects to sources, events, and knowledge across disciplines and cultures. Our cross-disciplinary approach enables scholars and interested members of the public to understand where Jewish, Muslim, Christian and other perspectives intersect in the text.

The first stream is named “Biblical Annotation and Hebrew Biblical Sources”. Throughout the work of annotation, this team has been opening different and complementary lines of research. The most connected with our annotation task has to do with the references and relations between the biblical chapters of the GGE with biblical, apocryphal and pseudepigraphical sources. We also pay special attention to the distinct use of Christian, Jewish and Muslim exegetical traditions and the connection between the Biblical accounts found within the GGE and in other Hispanic Bibles. This stream has also opened a new line of inquiry interested in locating what we define as “crypto-Jewish writers of the GGE”, Jewish collaborators at the Alfonsine court and scriptorium who were involved, anonymously, in the production and edition of an important amount of its Biblical chapters.

The second stream, “Philological Annotation and Textual Edition”, is mainly in charge of the new, and digital, edition of the GGE and is also responsible for the philological and linguistic annotations. This stream also devotes its time to the paleographic and normalized edition, lemmatization, categorization, and textual alignment. It has opened further lines of research connected to the study of Latin sources, studies on phraseology and morphosyntax and Galician and Portuguese translations of the GGE.

The third stream, “Arabic Sources”, is focused on the localization and study of the Arabic sources of the GGE. This stream locates the intertextual relationships between the GGE and Arabic historiography, Arabic literature and Islamic exegesis and thought, as well as the transmission of classical and Biblical material through the Arabic language. It also pays attention to the influences of the Arabic language on the Castilian language developing under Alfonso X.

The fourth stream is named “Gentile Sources”. This stream is responsible for annotating the chapters of the GGE that deal with ancient, non-Biblical material (e.g. Ancient Greek and Roman) material. Their main concern is to understand and describe the procedure of reading, translation, and attribution of meaning to which this material has been subjected as transmitted by the GGE and, also, to reconstruct the status of these classical sources at the time they were incorporated into Alfonsine historiography.

The final stream of Team 1 is dedicated to “Medieval Universal Histories Worldwide”. This stream compares the GGE to other universal histories and encyclopedic texts written in the medieval period, with attention to comparisons in terms of the scope and dimensions of these texts, the approaches to historiography, the literary references and the writing strategies employed.

The writing strategies of the authors of the GGE are a concern for all streams of Team 1. Different members of our team keep track and study aspects such as: the treatment of key female characters; historical, mythical, or sacred figures; spaces; verbal mappings; zoology; geography; etc. With the invaluable collaboration of student interns on the project, this team has also worked on the creation of glossaries for these various aspects of the text. Our collaborative online platform has been essential for sharing insights within and across these multiple streams.

Team 2, “Archival Research and Bibliography” works to identify, source, and curate all the primary and secondary resources of all our research activities, using digital tools such as Zotero to create shared repositories. Team 2 also builds partnerships with archives and advances research on documentary collections that shed light on our common goals. This team trawl through the documentary collections of Alfonso X and al-Andalus. One of the main research lines of the archival work is to understand and evaluate the relationship between the Chancery and the Scriptorium of Alfonso X. It is also interested in the identification and the prosopography of the members of the circle of intellectuals involved in the production of the GGE.

Team 3, “Translation”, are translating the text first into modern English, and later into modern French, with in-depth translators’ notes. Because AI tools are not equipped to translate from medieval languages, these translations will make possible the machine translation of the GGE into other modern languages. This team is conducting practice-based research into the benefits of collaborative and interdisciplinary translation work. As the translation is informed by the scholarship and edition work of Team 1, we analyze how the process of translation requires this team to reflect on nuances they otherwise would not notice and leads to deeper understanding of the text. We also consider how translation brings to light questions about gender in the text. As training is at the heart of the Translation team, the translation work is described in more detail in the training section below.

Team 4 (“Knowledge Mobilization”) will work closely with our partners to advance diverse knowledge mobilization activities, ranging from place-based workshops with emerging partners in North Africa to digital exhibits and facilitation tools that leverage the GGE to foster generative dialogues around conflict and cultural difference. We are poised to develop new transferable tools for digital humanities scholars, including a model for handwritten text recognition (training a Transkribus Public model for 13th century Castilian script, for instance). This intervention represents a major shift in the study of original sources. Advances in the study of archival sources have conventionally been limited to scholars with access to travel funds and highly specialized training in the handwriting and conventions of original scribes. While a portion of medieval manuscripts have been digitized, only those with highly specialized training have been able to decode the handwriting and conventions to make these texts legible. We will share both an exhaustive documentation of our model of collaborative work and the software comprising our collaborative platform (via GitHub and Zenodo), so other teams can adapt it, understand its design, and learn from it. Knowledge mobilization beyond the academy is detailed further below.

The foundational questions of this project are about inclusion. Our research design considers diversity and cultural sensitivity in our source texts as well as the implications of our work for communities that have traditionally been excluded from scholarship of the Middle Ages. Our digital platform will provide translations of source materials in two languages and capacity building so that scholars in underserved communities or without institutional support can use and collaborate with our team. We are actively engaging co-applicants, partners, and collaborators in North Africa to help shape our research questions as well as the expected outcomes of our research for their communities.

The scope and scale of our partnership and object of study make possible an extraordinary network of opportunities for trainees and emerging scholars. This project offers deep training with scholars from rare fields of study, practice in working in collaborative, cross-disciplinary methods, and opportunities to train at universities spanning three continents. A core principle of the project is that all our activities—including edition, translation, and knowledge exchange—are opportunities to train students and emerging scholars, as well as other stakeholders such as teachers and museum curators, to ensure the sustainability of the project. Through our research and knowledge mobilization activities, trainees and emerging scholars will generate robust portfolios demonstrating outputs such as translations, critical editions, open-source code, journal papers, and accessible research communications. As our partnership network grows, we will invite partners in sectors such as tourism, natural language processing, policy making, and memory work to offer career advice and help our team understand the diverse applications of technical skills.

Our annual ‘Translation and Digital Innovation in the Humanities’ intensive training in La Rioja, Spain, delivered in partnership between UBC, Exeter, and Fundación San Millán, demonstrates the coordinated work of our team to create experiential learning opportunities that build capacity among trainees and partners through the co-production of translations and related resources that will make cultural heritage universally accessible. Two successive UBC-Exeter Global Partnerships grants have supported two successful pilots of this innovative translation training program with five student interns from the University of Exeter MA Translation Studies programme. Inspired by the collaborative translation practice at Alfonso's court, this experiential learning program trains participants to develop translations of sections of the GGE individually and then gather to create and edit a translation which brings together ideas and solutions from each translator. As they develop skills and confidence, trainees progress to taking ownership over the translation of specific GGE chapters, gathering as a group throughout the process to workshop drafts. Within this process, digital platforms and communications are essential. Translators do not have to be experts in medieval Spanish language and culture because the platform gives access to the extensive notes made by the research teams, and a dictionary of Alfonsine prose, as well as allowing translators to post comments on the text with questions directed to the researchers. This is complemented with virtual monthly meetings with the international research team to finalize their edits and prepare the translation for open access publication via COLABORA. Our method of knowledge exchange between trainees and research teams improves both the translation and the research and edition of the text.

Building on these pilots, our translation initiative in La Rioja will advance professional development, mentorship, and relationship building for students, partners, and the local community. Participants begin with a week of cultural immersion and translation training co-hosted with the Fundación San Millán de la Cogolla. Experiencing Medieval Spain through spending time at this monastery brings the project to life for the students. In future years we will take advantage of specialist activities offered by the Fundación, such as Medieval manuscript illustration workshops. We will replicate this model with other aspects of the project, including the use of digital tools for transcription, edition, and French translation, expanding access to interns based in partner universities. This event will kickstart a continuing training programme that brings together trainees and practitioners from around the world for real-time translation, as well as capacity-building workshops and networking events. Trainees, in turn, will mentor subsequent peer cohorts.

In addition to traditional academic knowledge mobilization in the form of publications and conferences, this project will yield an innovative training model, a roadmap for humanities-based collaborations, and public access to cultural traditions and artifacts that have been systemically erased from our global heritage. A major achievement of the project will be making the entire GGE, including digitized manuscripts and detailed explanatory notes, freely available online, alongside the first complete translations into English and French. Data and analysis throughout this process will create a blueprint for digital applications to draw connections between sources, triangulate the meanings of words in languages no longer spoken, and restore the complexity that we lose when medieval manuscripts become printed books.

Our project takes an iterative approach to knowledge mobilization, prototyping initiatives with existing partners as we build trust with emerging partners in Latin America and North Africa. We are actively planning a two-stage knowledge mobilization pilot with two new partners: the Library of Kelowna (British Columbia, Canada) and the Lions Club (Colombia). The first iteration of this initiative will include a facilitated dialogue about cultural difference supported by examples of medieval knowledge exchange from our digital platform. We will test this initiative with UBC students and Kelowna community members before tailoring a version in Spanish for secondary school students in Medellín. Future iterations of this pilot will include offerings in the greater San Antonio area, home to the largest population of Syrian refugees in North America. We will work with our current and future education and cultural heritage partners around the world to adapt this approach for their local communities.

Our partnership network, digital infrastructure, and expertise in multiple languages create the foundations for accessible knowledge mobilization across languages as well as innovative approaches using infographics, visual mapping, Augmented Reality, and Virtual Reality. We will use open-source digital storytelling tools developed by Northwestern University Knight Lab to develop curriculum modules for educators suited to their student audiences, with one specific focus being materials for refugee students from the Middle East. Over the course of the project, we will create, evaluate, and refine a bank of materials in multiple languages. Through our research and knowledge mobilization activities, this project will inspire interest in language learning and translation, integrate cultural heritage into school classrooms, and facilitate positive civic dialogues around conflict and cultural difference.

Our focus on the GGE inherently engages a diversity of source materials from Muslim, Jewish, and Christian cultures as well as myriad languages, cultures, and knowledge systems. This confluence of voices and ideas brings generative and inclusive dimensions to our research, creating points of connection with the lived experiences of communities around the world. We are also mindful, however, that the sources we study were created during a historical period that created barriers to entry for women, people with different abilities, people of colour, and those without access to formal education and literacy. Studies of these sources require sensitivity to the ways that historical language may impact modern readers, and contextualizing the cultural protocols and assumptions embedded within these texts is a critical consideration as we seek to make these sources more accessible. Our team will provide annotations and resources to facilitate safe and productive engagement with these source materials. As humanities educators, we have the necessary expertise to help readers engage with difficult histories through dialogue, analysis, and cultural understanding.

The General e grand estoria is one of the most significant, and yet least known, sources of medieval knowledge. Its staggering scope and dimensions, together with the diversity of sources it references, make it impossible to study from any disciplinary silo. Through harnessing a range of digital tools, “The Confluence of Religious Cultures in Medieval Historiography” brings together scholars from a multitude of disciplines, cultures, and backgrounds - following the example set by Alfonso X - to explore and share the full complexity of this universal history.

Today’s academic landscape perpetuates colonial biases and inequities such as the scarcity of research infrastructure in regions that produced many of our most valuable cultural heritage artifacts. Advances in the study of archival sources have conventionally been limited to scholars with access to travel funds and highly specialized training in the handwriting and conventions of original scribes. This project facilitates linguistic and cultural translation that has not previously been possible through our unique tools, expertise, and partnership approach. Building upon COLABORA, we are poised to develop a suite of tools for digital humanities scholars that represents a major shift in the study of original sources. We will work closely with diverse communities, museums, schools, cultural organizations, and other partners to create new frameworks and tools for engaging with cross-cultural differences in public dialogues. In short, we turn to the 13th century to find a compelling example of how curiosity can effectively create communities of knowledge, even when cultural lines may seem impossible to cross.

*: We are writing on behalf of a team of over forty scholars,

many of whom shared ideas for this article. To see all the team members, please

visit https://dege.ok.ubc.ca/