1. Introduction

This paper studies MINUSMA (Mission multidimensionnelle intégrée des Nations unies pour la stabilisation au Mali), the United Nations (UN) peace operation in the stagnant armed conflict of Mali. It was established by the UN Security Council (UNSC) after an intent of secession and takeover of Northern Tuareg and Islamist factions, repelled by the French Armed Forces, and requested by the Malian government. The object of study is the presence of counterterrorist and/or counterinsurgent elements within MINUSMA since the creation of the mission in 2013 up until 2020. This approach will allow us to research on a concrete issue while synthesising previous literature on peacekeeping and analyse the mission’s mandate, operations, structure and relevant international actors.

MINUSMA is an ongoing operation, the next-to-last one before MINUSCA (Mission multidimensionnelle intégrée des Nations unies pour la stabilisation en République Centrafricaine), and the biggest military mission present in Mali, a country with more than 68 states which are present with uniformed personnel combining all international missions. This mission is also one of the most militarily engaged ones in UN peacekeeping history, with 250 MINUSMA casualties as of November 2021 (United Nations Peacekeeping, hereafter [UNPK], 2021a), usually called the most dangerous contemporary UN mission (Sieff, 2017). Among other reasons, the complex security situation has led MINUSMA to be considered a “laboratory” of peacekeeping facing “new threats” (MINUSMA, 2017), in a context of a momentum for robust operations together with the Force Intervention Brigade in Democratic Republic of Congo’s MONUSCO (Mission de l’Organisation des Nations unies pour la stabilisation en République démocratique du Congo) and the Regional Protection Force in South Sudan’s UNMISS (UN Mission in South Sudan) (Karlsrud, 2017). Furthermore, the topic is also pertinent due to the current state situation in Mali, with the ongoing exit of French forces and the entry of Russian mercenary forces of the Wagner Group, which will surely influence MINUSMA.

Taking all this into account, MINUSMA faces the problem of combining the peacekeeping nature and Security Council guidelines with being victims of insurgent and terrorist attacks. In this sense, we will consider if MINUSMA adopts a nuanced perspective in relation with other UN peace operations and carries out counterterrorist and/or counterinsurgent tasks, with the subsequent implications Therefore, the research questions are the following:

A. Main question:

- 1.

In the framework of an armed conflict with the presence of terrorist and insurgent actors, has MINUSMA, as a peace operation with the basic mandate of stabilisation, carried out any counterinsurgent or counterterrorist tasks? If so, which ones?

B. Subsidiary questions:

- 1.

Do these tasks appear on the mandate or are they supervened?

- 2.

Which impacts has it had?

- 3.

Has there been coordination or cooperation with the French mission

in these tasks?

Moving on to the hypotheses, the preliminary one (H1) is that MINUSMA has conducted counterinsurgent and supporting counterterrorist tasks. The subsidiary hypotheses are: (H2) even if these tasks are not explicitly in the mandate, they arise from it, as a response to the dynamics of the armed conflict and/or the French authorities’ interest; (H3) a fact that impacts on the interests of Security Council members and disrupts the UN peace operations doctrine; eventually, (H4) it is presupposed that the mission strongly cooperates with the French operation.

To answer the questions, we will outline the context (2.1) of terrorism and insurgency, especially that of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency, globally and case-based, to then explain the historical precedents of the war and the subsequent creation of MINUSMA. Second, in the framework of analysis (2.2) we will discuss the theoretical tenets of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency in relation to peace operations, key definitions of the two elements and a final methodological roadmap. Then, we will enter into the case study with a mandate analysis (3.1.1) of the UNSC resolutions and its context; afterwards, we analyse the organizational and operational structure (3.1.2); followed by a review of its implementation (3.2) either in a premeditated or a supervened manner; finally, we will look at its impact (4) on the ground in the conflict, the cooperation or coordination with the French operation and the repercussions on peacekeeping doctrine; to end with some concluding (5) remarks and findings.

2. Context & framework of analysis

2.1. Context

9/11 is a crucial date when talking about terrorism. Many see it as the beginning of a wave of new terrorism, even if we experienced other attacks in the 1990s. But regardless of these considerations, it is clear there was indeed a new wave of counterterrorism. The international context of terrorist groups in the 2010 was constructed around two main organizations, Al Qaida and Daesh, as well as other regional and local groups. A turning point was the fall of Ghaddafi and the Libyan Civil War, which disseminated terrorist and insurgent groups throughout the Sahara-Sahel region in terms of leaders, organizations, armament and ideology (Hüsken & Klute, 2015, p. 324).

This is also the case of Mali, where many former Tuareg fighters along Ghaddafi’s forces left the war-torn country and returned to the North of Mali, home for the Tuareg Amazigh people, as well as Islamist extremists (Hecker & Tenenbaum, 2021). Then, in 2012 the fifth Tuareg Rebellion took control of Northern Mali, led by the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (Mouvement national pour la libération de l’Azawad, MNLA), its Islamist scission Ansar Dine, and other jihadists as MUJAO (Mouvement pour l’unicité et le jihad en Afrique de l’Ouest, Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa) or AQIM (Al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb). So, the MNLA, together with MUJAO and Ansar Dine, proclaimed the independent State of Azawad. However, the alliance degenerated into internal struggle, resulting in a more Islamist-leaning Azawad, starting an offensive against the government-controlled South and its capital, Bamako.

In this context, in 2012, ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) approved the African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA), in partnership with the African Union (AU), under the auspices of the UN Security Council, with a slow pace of military deployment (Van der Lijn, 2019). Afterwards, with the pretext of a possible Islamist and Jihadist takeover of the whole of Mali, a renewed offensive in 2013 triggered the deployment of the French Opération Serval at the request of Mali, a military intervention that stopped rebel advances and regained control over great portions of the centre and north of the country, but without the Malian Armed Forces accompanying them, only with AFISMA’s West African contingents. Thus, with a purely military control of former Azawad areas, the Tuareg MNLA took advantage of the window of opportunity the French forces had given them defeating their Islamist rivals and coped many formal and informal institutions in towns and cities of Northern Mali (Hecker & Tenenbaum, 2021).

Finally, in such an unstable territory, with low popularity of state authorities, AFISMA was rehatted into the UN Security Council-launched MINUSMA in 2013, at the request of France and the United Sates. Then, with the accord of ECOWAS, the AU and Mali, most of the contingents of the African-led mission were transferred to the UN operation, along with the civilian monitoring UN Office in Mali (UNOM) (Van der Lijn, 2019).

Eventually, in 2015, the Malian Government, their allied militias of Plateforme, and the MNLA-led Coordination of Azawad Movements negotiated a Peace and Reconciliation Agreement in Algiers consisting of dialogue, decentralisation and ceasefire. However, violations of the accords have been recurrent, and violence continuously hits areas controlled or targeted by jihadist elements, non-parties of the accords, paving the way for an insurgent and terrorist-struck scenario where the UN peace mission is operating.

2.2. Framework of analysis

As saliency of terrorism and insurgency has risen, countering both acts of political violence are ever more prominent. Also, it has been implemented in a wide range of security forces and, more recently, some authors have highlighted that some peace operations include counterterrorist and/or counterinsurgent tasks.

This study works with the tenet that counterterrorism and counterinsurgency are different in its nature and development. Nevertheless, as Boyle (2010, p. 352) states, both countering campaigns can be carried out simultaneously in a same war theatre, and some effects can be complementary. In this line, we will study counterterrorism and counterinsurgency roles in a same territory, Northern and Central Mali, and by the same operation, MINUSMA.

Historically, we can find examples of peace missions that involved or evolved into counterinsurgency. It is the case of the US-led ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) in Afghanistan, initially framed as a peacekeeping mission, but later turned into a counterinsurgency operation (Zaalberg, 2012, p. 80). A blue helmets example would be the UNSC authorization to ONUC (UN Operation in the Congo) to directly combat, with counterinsurgent methods, the rebel Katangese troops in Congo-Léopoldville in the 1960s (Zaalberg, 2012). But even if we may label the Katanga case as a historical exception and the Afghan ISAF as a not-truly peace operation, the Malian context is probably prone to force a peace mission as MINUSMA to conduct counterinsurgent tasks.

Counterinsurgency takes place mostly within the state, and it places the centre of gravity in the population, rather than conventional military or geographic objectives (Gventer et al., 2014, p. 21). In this line, it can use coercive measures as well as indirect methods like provision of security, governance or development; always bearing in mind the vital importance of not alienating the population from the government (Boyle, 2010, p. 343). In addition, military field manuals and academic authors widen the conception to include “military, paramilitary, political, economic, psychological and civic actions taken by a government to defeat insurgency” (Ucko, 2012, p. 68), combining coercion and co-option. Therefore, we make the case that these objectives and methods can be close to those of a stabilization and peace operation as MINUSMA.

Regarding counterterrorism and peace operations, since the Global War on Terror and the subsequent spread of this preoccupation, the UN is in a “state of flux when it comes to policy development on the issue of counter-terrorism and countering and preventing violent extremism”, Karlsrud argues (2019, p. 158). And a key tool of the UN system in this are peace operations. Nonetheless, it is widely shared, and acknowledged in this paper, that UN peace missions are not entirely counterterrorist operations; and precisely for this, it is significant to examine counterterrorist elements in this mission, because it is seen as an example of the initiation of the UN into counterterrorism tasks by several authors.

Literature agrees on four peacekeeping generations, but some scholars start to see the emergence of a fifth, having a growing emphasis on stabilization and a degree of counterterrorism, as envisaged in the UN Counter-Terrorism Strategy, where there is a new trend in UN peace operations in which they are expected to deal with terrorists and violent extremists. This progressive incorporation of counterterrorism is displayed by Karlsrud, who affirms that MINUSMA “has become the laboratory for testing whether UN peace operations actually are able to take on these [counterterrorist] challenges” (2019, p. 158). Smit (2017) affirms that it has been argued that MINUSMA “may already have crossed the line into ‘[counterterrorism] mode’” (p. 5), using “advanced military capabilities and assets such as Special Operations Forces and drones to conduct ISR [Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance] missions on terrorist groups [...] and has shared actionable intelligence [...] with the French ‘[counterterrorism] force” (Smit, 2017).

Finally, counterterrorism in peace operations is potentially circumcribed to “areas of kinetic military operations, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), border control, and policing and criminal justice” (Smit, 2017, p. 3). Furthermore, with a prolonged insurgent and/or terrorist presence, we usually find parallel and/or successive missions: for example, peace operations, military forces, either regional or unilateral, and others (Smit, 2017, p. 11). Indeed, this applies to the Malian case: first the regional ECOWAS-led AFISMA, transformed into the universal multilateral MINUSMA, the regional G5 Sahel coalition for counterterrorism, counterinsurgency and border control, the European Union Training Mission (EUTM), and the French intervention, first local, Opération Serval, and afterwards regional, Opération Barkhane. Therefore we also study the impact of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency in MINUSMA in relation with other missions, and the division of labour.

With all this literature in mind, we need to define the two key concepts to analyse the mission in relation to counterterrorism and counterinsurgency, noting that, as Williams puts it, “not everything that can be done to combat terrorism ordinarily bears a label of ‘counterterrorism’” (2008, p. 377), and the same would apply for counterinsurgency. So, we will have to analyse not only the means, but the goals and strategy. Using the definition of the corresponding US Field Manual “counterinsurgency is comprehensive civilian and military efforts designed to simultaneously defeat and contain insurgency and address its root causes” (Department of the Army, 2014, p. 2). In line with the civilian aspect, the Peace terms glossary emphasizes the “efforts [...] to separate the insurgents from the population by winning their “hearts and minds”, typically by undertaking badly needed reforms” (Snodderly, 2011, p. 30). Thus, we will work with the following definition:

Counterinsurgency is a set of efforts designed to contain and defeat insurgent groups, this is, organizations that violently uprise to challenge or seize political control of a territory, by the civilian means of separating the insurgents from the population, addressing its root causes, and militarily stop and reverse acts of subversion and violence.

In the case of counterterrorism, the Military Dictionary of the US Department of Defence defines it as those “activities and operations taken to neutralize terrorists and their organizations and networks to render them incapable of using violence to instill fear and coerce governments or societies to achieve goals” (Department of Defence, 2021, p. 52). Meanwhile, the Historical Dictionary of Terrorism states that counterterrorism comprises antiterrorism as the “efforts to deter, contain, and punish terrorism by means of domestic law enforcement, incident response and containment, and education”, together with a more restrictive notion of counterterrorism encompassing “military and intelligence efforts to prevent or contain or to retaliate against terrorism” (Sloan & Anderson, 2009, p. 225). A last piece of literature by Williams (2008) on counterterrorism understands that it is essential to shape incentives of terrorists to halt the violent pathway to use peaceful means. It remarks key elements of counterterrorism, including incident management, public communications, defensive security measures (labelled also as anti-terrorism), diplomacy, financial control, intelligence, criminal prosecution and military force (Williams, 2008). Consequently, the definition used here will be the following:

Counterterrorism is a set of activities, operations and wider policies that have

the aim of deterring, containing, punishing, retaliating or neutralizing terrorist

individuals, organizations and networks to make them incapable of conducting

a spread of fear or coercing authorities or societies through political violence,

by the means of domestic law enforcement, incident response and containment,

education, military operations and intelligence.

The study period of this paper is since the creation of the operation in 2013 up until 2020, to have a certain historical perspective. We will follow a qualitative and inductive methodology, departing from a case study, MINUSMA, to study the relation between peace operations, counterterrorism and counterinsurgency in general terms. Once we have the two key concepts, we will proceed with an empirical-descriptive analysis of the mission on said tasks. Finally, we will contend the impact this has had on the ground and on peace operations doctrine. The study will use the revision of academic literature, analysis of primary sources as key UN Security Council resolutions, other documents of the UN system and discursive analysis on relevant actors.

In sum, this study holds the assumption that due to the volatile and violent context with terrorists and insurgents, in the framework of an increasing peace enforcement tendency, UN peace operations can develop counterterrorism and counterinsurgency. Thus, we intent to corroborate this in the case of MINUSMA.

3. Case study: MINUSMA

This section takes the UN mission in Mali as a practical case to understand a foreseen shift in UN peace operations. It consists of a (3.1) Mandate & operationalization, together with its (3.2) Implementation on the ground.

3.1. Mandate & operationalization

This subsection captures those elements relevant or specific for counterterrorism and counterinsurgency of the Security Council (3.1.1) Mandate, followed by a detailed and compared study of both resolutions. Second, we look at how this was translated into the (3.1.2) Organizational & operational structure of the mission.

3.1.1. Mandate

A mandate is constituted by the UNSC resolutions establishing and extending the mission, its resources, goals and means. In MINUSMA we find two key documents: Resolution 2100 (2013) (hereafter called foundational resolution), creating the mission, and Resolution 2164 (2014) (hereafter called expansive resolution), expanding the mission’s scope, strength and goals. Both documents were approved under the powers of Chapter VII of the UN Charter.

-

Foundational resolution: the preceding report of the Secretary-General on Mali (UN Security Council, hereafter UNSC, 2013a) stated that many Malian actors, the ECOWAS and the AU “requested a United Nations force to undertake combat operations against terrorist groups” (UNSC, 2013a, p. 13). Nevertheless, the top UN official framed the sought enforcement mandate – substituting AFISMA and Opération Serval and combating insurgents and terrorists– as inadequate. The Secretary-General, taking into consideration the military training, equipment and experience of peacekeepers, understood such a mission as “falling outside peacekeeping scope and doctrine” (UNSC, 2013a, p. 13). Thus, he proposed the UNSC to start a UN political mission along with AFISMA and, when combats and threats eventually decrease, UN peacekeepers could be brought. A second option was to enforce a Chapter VII robust peace mission, taking over AFISMA, likely facing asymmetric threats, along with a parallel counterterrorism force. He finally remarked the importance of a clear distinction between core peacekeeping and peace enforcement with counterterrorism (UNSC, 2013a, p. 19).Finally, the robust option was decided and in the Security Council debate after the approval of Resolution 2100, Mali acknowledged that it was an “important step in a process to stem the activities of terrorists and rebel groups in Mali” (UNSC, 2013b, p. 3), stating that many terrorist cells still posed a threat after the French intervention. On his behalf, Russia was “disturbed by the growing shift towards the military aspects of the United Nations peacekeeping” (UNSC, 2013b, p. 2).

-

Expansive resolution: while concrete elements will be discussed below,

it is worth noting that whereas the foundational resolution was approved

in a determined situation, outlined in (2) Context & framework of

analysis, the circumstances evolved and in 2014 the expansive resolution

was drafted in consonance. THe new resolution stated there were breaches

of a preliminary ceasefire agreement, with violent clashes in Northern

Mali, attacks on Malian security forces and government officials, and

the seizure of government buildings and towns, establishing “parallel

administrative structures” (UNSC, 2014, p. 2) by the MNLA. Plus,

MINUSMA personnel were targeted, a peace force that, in view of the

UNSC, was in a “slow pace of deployment” (UNSC, 2014, p. 4). All within a framework of a “fragile security situation”, continuously struck

by “terrorist organizations, including Al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb

(AQIM), Ansar Eddine, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West

Africa (MUJAO), and Al Mourabitoune”, claiming they “constitute[d]

a threat to peace and security in the region and beyond” (UNSC, 2014,

p. 2). Some of these acts as the assassination of officials can be labelled

as terrorist, while others as the occupation of public buildings and the

claims of political institutionality are proper to insurgencies.

-

Counterterrorism & counterinsurgency elements analysis: the table

1 displays counterterrorism and counterinsurgency elements of both

resolutions. e expansive resolution column shares the elements

outlined in the foundational one, while specifying the new elements

included in 2014. It is composed of three basic domains: 1) military

aspects linked to kinetical and operational aspects; 2) civic-political and

institutional aspects; and 3) MINUSMA’s interrelations with other

forces

Table 1

Counterterrorism & counterinsurgency elements of MINUSMA’s UN Security Council resolutions

own elaboration based on UNSC Resolution 2100 (2013) & Resolution 2164 (2014).

own elaboration based on UNSC Resolution 2100 (2013) & Resolution 2164 (2014).

|

UNSC

Resolutions

|

Foundational Res.

100 (2013)

|

Expanding Res.

2164 (2014)

|

|

Military

|

Stabilize & secure population centres, restore state control.

Active measures to dissuade & prevent the return of armed elements.

Protection of civilians under imminent threat, within capabilities and area.

|

Expand presence with long-range patrols beyond population centres in North of Mali.

Extend operations in North in complex security environment including asymmetric threats.

|

|

Civic-political & institutional

|

Good offices & assisting to restore the constitutional order.

Help for transition, dialogue & civil society connection.

Watch over human rights and international humanitarian law.

|

[Nothing relevant new]

|

|

Interrelations with other forces

|

Importance of Malian Security Forces & welcome EUTM.

Support authorities on bringing war criminals to justice.

Authorize French forces to use all means necessary & support MINUSMA if grave and imminent threat.

|

Operational coordination with the Malian Defence and Security Forces.

|

As a quantitative-discursive hint, in the first resolution the terms terrorists, terrorism and terrorist account for 18 times, whereas it does 32 times in the expanding one. Furthermore, we should remark that insurgency or its derivates are not mentioned in any of the two documents. Instead, we find the compound terrorist, extremist and armed groups altogether several instances.

To begin with the strict analysis, in the preambulatory clauses, the foundational resolution affirms that “terrorism can only be defeated by [...] all States, and regional and international organizations to impede, impair, and isolate the terrorist threat” (UNSC, 2013c), implying the active involvement of the UN and its MINUSMA in the struggle. Also, it requests UN authorities to conduct good offices to contribute to the restoration of the constitutional order, to the transitional road map and dialogue within a peace and reconciliation process, with the civil society, illustrating the weight of the social interaction, a shared element with the counterinsurgency notion of not alienating the population.

Moving on to the commanded tasks, MINUSMA should stabilize and secure population centres and help restore state authority (UNSC, 2013c, p. 7). Also, it commands to “deter threats and take active steps to prevent the return of armed elements”, especially in the North of Mali (UNSC, 2013c, p. 7), which are obviously terrorist and insurgent. Likewise, the resolution commends MINUSMA with the protection of civilians under imminent threat of physical violence, only “within its capacities and areas of deployment” (UNSC, 2013c, p. 8), while the expansive resolution did not narrow it in those terms. Concerning other forces in Mali, MINUSMA’s mandate is not neutral as traditional peacekeeping missions were, instead, UNSC highlights the importance of Malian Security Forces, aided by the EUTM, and authorizes, under Chapter VII, the French forces to combat rebels and intervene to support MINUSMA if it is under grave and imminent threat (UNSC, 2013c).

Expansive resolution 2164 shows more robustness and approaches the mission towards counterterrorist and counterinsurgent camps. First, it definitely sets aside impartiality and provides “operational coordination” (UNSC, 2014, p. 6) with the Malian Armed Forces, siding with a belligerent faction. It seeks to “expand its presence, including through long-range patrols [...] in the North of Mali beyond key population centres, notably in areas where civilians are at risk” (UNSC, 2014, p. 6); in a sense, to extend to rural areas and carry out their deterrence and protective tasks, precisely where there is more presence of terrorists and insurgents (Sandor, 2017). Furthermore, the Security Council mandates MINUSMA to “extend its operations in the North of Mali [...] in a complex security environment that includes asymmetric threats” (UNSC, 2014, p. 9), and these kinds of asymmetric threats include insurgent and/or terrorist groups (Buffaloe, 2006).

Therefore, if under Chapter VII MINUSMA is authorized to use all means necessary, not only in self-defence, but in active defence of the mandate, if this one, as we have seen, includes a deployment in areas with a notable presence of terrorists and insurgents, we can infer that MINUSMA ought to conduct counterterrorist and counterinsurgent tasks.

Plus, an additional resolution number 2294 (UNSC, 2016) states that MINUSMA would have to “anticipate, deter and counter threats, including asymmetric threats”, as well as “robust and active steps to protect civilians”, with “active and effective patrolling” and “prevent the return of armed elements [...], engaging in direct operations pursuant only to serious and credible threats” (UNSC, 2016, p. 8). It compels to “countering asymmetric attacks in active defence of MINUSMA’s mandate” with “robust and active steps to counter asymmetric attacks”, and to “ensure prompt and effective responses to threats of violence” (UNSC, 2016, p. 9), once again, but even more manifestly, the UNSC clearly mandates the countering of asymmetric —terrorist and insurgent— elements.

3.1.2. Organizational & operational structure of the mission.

Now, we are going to lay out MINUSMA’s structure design to accomplish the goals. MINUSMA accounts, as of March 2022, for 18.108 personnel, of which we find 12.286 military troops and 1.745 police officers (United Nations Peacekeeping, hereafter [UNPK], 2021a), ranking third among ongoing UN peace missions (UNPK, 2021b). Concerning troop contributing countries, as of November 2021, all but two of the top ten contributors are African, mostly West African, making it a widely French-speaking mission (UNPK, 2021a).

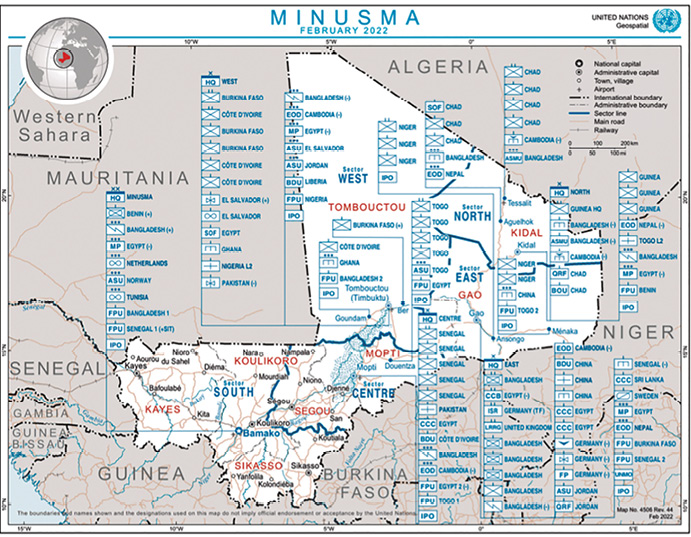

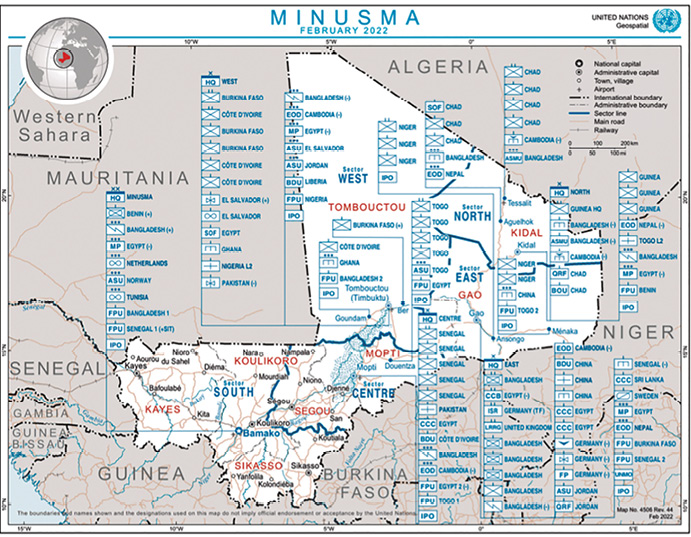

This personnel has its headquarters in the capital Bamako, and it is geographically structured in 13 locations in different sectors: North, South, East, West and the more recently created sector Centre, probably due to the increasing instability in the border with Burkina Faso and the Liptako-Gourma triple frontier zone1. The organization and distribution of the mission as of February 2022 described here can be grasped in figure 1.

Figure 1

MINUSMA geographic and organizational deployment

United Nations Geospatial (2022).

Figure 1

MINUSMA geographic and organizational deployment

United Nations Geospatial (2022).

As it can be seen in the map, MINUSMA is set to cover a large area, much of which under extreme climate. This dispersion of units implies a huge physical separation between the robust units in the centre and north of Mali, and the force commander and the main intelligence unit —which will be discussed below—, located in the capital (Rietjens & Ruffa, 2019, p. 211).

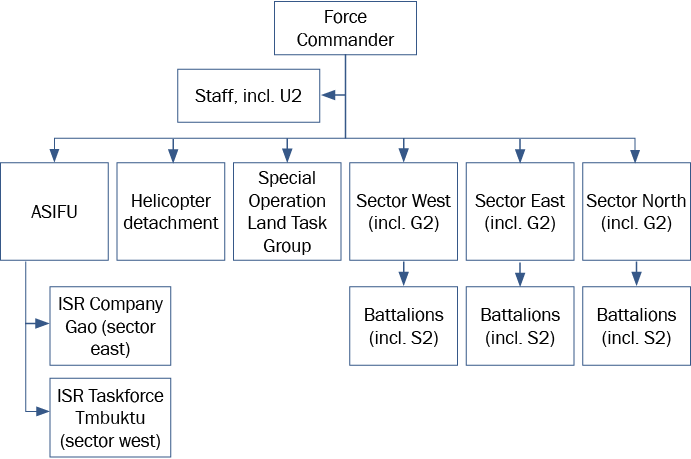

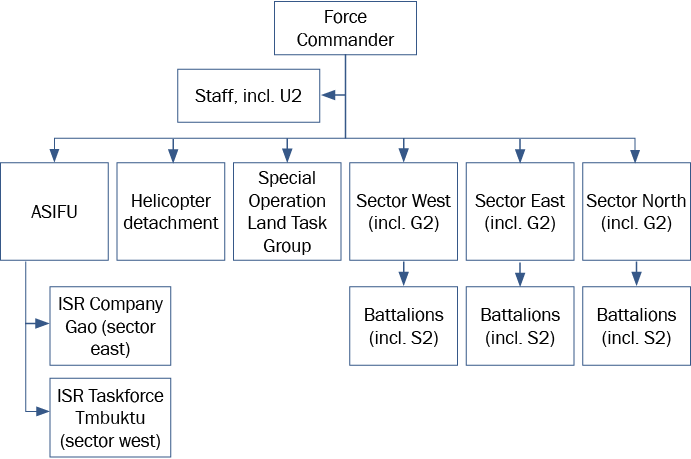

This leads us to the organization of the mission. Whereas there is a formal supranational hierarchical structure, with most decision authority centred in the force commander, MINUSMA command and control lines are quite bypassed, and national militaries take precedence (Rietjens & Baudet, 2017). Within robust military units of the different sectors, we can find a Quick Reaction Force and counter-IED (Improvised Explosive Device) teams (Van der Lijn, 2019); besides, there are three capabilities that are relevant to counterterrorism and counterinsurgency: UN Police, special forces and intelligence units.

UN Police established MINUSMA Task Force on Counter-Terrorism and Organized Crime, supporting Malian law enforcement, judiciary and corrections (Boutellis & Tiélès, 2019). Plus, a report of the Secretary-General on “Activities of the United Nations system in implementing the United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy” (UN General Assembly, hereafter [UNGA], 2016) included the UN Police Serious Crime Support Unit within the capacity building on counterterrorism.

Besides, the mission incorporated a Special Operations Land Task Group, whose units and assets come in large part from Afghanistan’s War NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) partners (Rietjens & Ruffa, 2019). This special forces’ unit, not very common in UN peace missions, rather that kinetic operations, is commended to carry out intelligence-gathering on the ground in complex security situations in northern Mali.

Concerning intelligence, the aforementioned Secretary-General report on UN Counterterrorism Strategy implementation (UNGA, 2016) listed the deployment of a military intelligence unit in MINUSMA to tackle terrorist groups operating in northern Mali: the All-Sources Information Fusion Unit (ASIFU) (Karlsrud, 2017). This unit is set to coordinate with each sector headquarters, which have their own intelligence staff. These tasks make MINUSMA the only UN peace mission with “organic military intelligence-gathering and processing capability” (Cherisey, 2017, p.1), emerged out of a push from European countries and with European personnel and material. ASIFU is functionally differentiated and a separate unit under direct authority of the commander (Rietjens & Baudet, 2017). ASIFU has its conceptual origins in the intelligence unit of Afghanistan’s NATO ISAF (Karlsrud, 2018), including capabilities as human intelligence operators, unmanned surveillance drones and attack helicopters, in addition to private contractors’ as well as open-source intelligence (ibid., 2018). Many of these capabilities drew “on Western experiences from counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operations in Afghanistan and Iraq” (Karlsrud, 2017, p. 1220). See figure 2 for an organizational diagram of the mission.

Figure 2

MINUSMA organizational structure

Rietjens & Ruffa (2019).

Figure 2

MINUSMA organizational structure

Rietjens & Ruffa (2019).

All in all, a part of what was planned was briefed by the French ambassador to the UN after the foundational UNSC resolution was passed:

[…] if in the city of Timbuktu there are terrorist cells, they [MINUSMA] will dismantle them. It is a robust mandate, it is a mandate of stabilization, but it is not an anti-terrorist mandate, they are not going to chase the terrorists in the desert. [...] MINUSMA forces will be able to conduct ‘anti-terrorism activity’ if the terrorists ‘come to town’. (Bannelier & Christakis, 2013, p. 872)

Nevertheless, what role has MINUSMA actually taken throughout the implementation of the mandate? If the mission is structured and mandated not only to prevent and mitigate attacks, but also to counter asymmetric threats, being in the Malian context, it means confrontation with insurgents and terrorists. Thus, whether a defensive-passive role or an active-countering role has been conducted will be discussed in the next section.

3.2. Implementation

This section outlines MINUSMA activities in line with the mandate (3.2.1 Premeditated manner), and those that fall outside the initial scope of the mission (3.2.2 Supervened manner), due to the unravelling security situations.

3.2.1. Premeditated manner: operational application of the mandate

Although this paper argues that counterterrorism and counterinsurgency are part of the mandate, it was not explicit on the resolutions. Then, for instance, MINUSMA’s Force Commander briefed to the UNSC that “in a terrorist-fighting situation without an anti-terrorist mandate or adequate training, equipment, logistics or intelligence to deal with such a situation” (Karlsrud, 2019, p. 158) they were not manifestly tasked to take direct action against asymmetric threats at the beginning. Nevertheless, supporting state authorities to tackle these was clear: the mission’s aid to the “elaboration of a national strategy to counter both organised crime and terrorism” and to the “establishment of a specialised judicial unit on terrorism and transnational organised crime” (UNGA, 2016, p. 22). MINUSMA also collaborated with the constitutional reform, the peace and reconciliation process and the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) process.

The mission was included in the UN counterterrorism strategy implementation report for the deployment of a military intelligence unit aimed at terrorists in the North of Mali, a Tactical Operations Centre and a capacity building programme for national counterterrorism brigades and a UN Police Serious Crime Support Unit (UNGA, 2016).

For instance, within the mandate framework of extending operations in a North with asymmetric threats, a special forces commando undertook a covert monitoring insertion in a northern village with terrorist presence, without direct engagement, as it was not explicitly mandated by the Security Council (Cherisey, 2017).

3.2.2. Supervened manner: facts that may have shaped the implementation

UN peace forces do not have much manoeuvring room, but local terrorist and insurgent activities can lead MINUSMA to deviate from its mandate, or to interpret it in concordance with the ground situation: a deteriorating environment where blue helmets are among the primary targets (UNSC, 2019). This means understanding the mandate as having more counterterrorist and counterinsurgent elements, paving the way for rather supervened actions.

The Algiers Peace Agreement (2015) is key. It differentiates between signatory compliant armed groups and non-signatory terrorist groups, meaning that the former are legitimate and should be treated as such, whereas the latter are excluded from dialogue and negotiation, because, as it is usually said, you cannot negotiate with jihadist terrorists (Charbonneau, 2019b). Nonetheless, as Van der Lijn (2019) states, boundaries between signatory, non-compliant, terrorist and criminal actors are blurred and fluid. Hence, catego-rization as non-signatory terrorists induce to treat as such actors that are not compliant with the Algiers accords, legitimizing counterterrorism. Because if the actors confronting MINUSMA are terrorists, good offices and negotiations —as requested in the mandate— are not a proper solution to illegitimate actors to have dialogue with, so countering them is the answer.

One example of an extensive interpretation of the mandate was an attack against MINUSMA in Kidal in 2018: a suicide IED vehicle, mortar bombs and firearms. It triggered a robust response, where blue helmets not only repelled the assault, but also pursued the assailants (UNSC, 2019). Indeed, Rietjens & Ruffa (2019) affirm that special forces (seen in 3.1.2 Organizational & operational structure of the mission) “often deviated from their objective to gather intelligence” (p. 395) and acted like they had an active counterterrorism mandate. Even, their commander said that the unit went to Mali to “kill people [,] hunt people and arrest them” (Rietjens & Ruffa, 2019, p. 395). A fair example of this is an operation that took place in 2016 in a northern town, where the special forces were inserted to “gather intelligence on terrorist presence” and even “to try and apprehend suspected terrorists” (Cherisey, 2017, p. 7).

4. Impact

4.1. On the ground with insurgent & terrorist groups

Counterterrorist and counterinsurgent elements of the mandate and tasks carried out have crucial consequences in the conflict. Supporting the state and being deployed in non-controlled areas, as well as proactive and robust operations with all necessary means “comes close to peace enforcement” (Hellquist & Sandman, 2020, p. 25), and make MINUSMA a “party to the conflict” (Neethling, 2019, p. 68). By conducting such tasks, the mission loses its presumed impartiality, because it involves a designation of an enemy, not being neutral, leading to more risks and casualties. This, in turn, makes that only those troop contributing countries that are willing to take such risks are those which have stakes in the conflict (Smit, 2017). Simply put forward, “sending out a patrol might work to deter an armed group in the Congo from engaging in violence, but it has the opposite effect in Mali” (Sieff, 2017), as armed groups target peacekeepers, perceived as enemies. Eventually, this perception, not only by insurgents and terrorists, but also by local civilians, can contribute to a bunkerization of the mission, por example, forces limited to staying within camps without real engagement on the ground (Smit, 2017).

This is also due to the deterioration of the mission’s legitimacy. As an example, intelligence activities and surveillance drones are understood as spying, and local populations can be mistrustful of blue helmets (Karlsrud, 2018), and even more if this information is shared with foreign operations as Barkhane, in addition to cases of sexual exploitation and abuse by blue helmets (Van der Lijn, 2019). The lack of legitimacy of led the EUTM to consider the confusion among them a potential security risk, as a report highlighted “how an angry mass of people mistook EUTM for MINUSMA” (Hellquist, 2020, p. 29).

Multilateral missions involve a great deal of civil and political personnel, so the lack of legitimacy jeopardizes them, as well as UN agencies, funds, programmes and NGOs working with MINUSMA, due to the links with a party to the conflict, as a so-called collateral damage (Karlsrud, 2017). Moreover, counterterrorism and counterinsurgency in peace operations questions the capacity of UN civilian staff and human rights observers, making UN military personnel uncomfortable while being monitored. It can also make host governments reluctant to share information with the force to restrict the civilian component’s room of action (Smit, 2017). Eventually, human rights violations in the name of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency are a breeding ground for legitimacy deterioration, as in words of the Secretary-General they constitute the terrorists’ “best recruitment tools” (Karlsrud, 2017, p. 1225).

4.2. Cooperation & coordination with the French mission

Although other international missions are also relevant, as this study analyses counterterrorism and counterinsurgency, it is vital to understand the coordination or cooperation with the paramount foreign military force in Mali and the Sahel on these matters, Opération Serval, later on Barkhane.

Doctrinally, the UN affirms that as peace operations are not suited for nor capable of military counterterrorism, other regional organizations or ad hoc coalitions should conduct these tasks (Smit, 2017). In this line, the Secretary-General, while providing options to the UNSC before mission’s creation, stated that “it is critical that a clear distinction be maintained between the core peacekeeping tasks [...] and the peace enforcement and counter-terrorism activities of [a] parallel force” (UNSC, 2013a, p. 19), needing a “close coordination and cooperation” between both forces (UNSC, 2013a, p. 15).

In 2017, an extending resolution (2359) urged UN and French forces to “ensure adequate coordination and exchange of information” (UNSC, 2017, p. 3), keeping separate tasks, for example, the division of labour (Charbonneau, 2019b). A priori, MINUSMA deals with legitimate political actors while the French mission does so with terrorists (Charbonneau, 2017). This comes from the conception that peacekeeping is “morally distinct from warfare, counterinsurgency and counterterrorism” (Charbonneau, 2017, p. 419), as in the latter ones there is an identification of an enemy to be defeated, and in peacekeeping there is a peace to be kept, in theory. Nevertheless, differentiation among all armed groups in Mali, and thus, the division of labour, is not clear at all. This blurred line between the two objectives of peace operations and of the French military is at least difficult to draw. The premise of the division of labour is that one can distinguish between non-terrorist and terrorist, among groups that are compliant with the peace accords, the non-signatory, terrorists, insurgents, groups in DDR process, etc., so to then differentiate between counterterrorism and peacekeeping tasks. However, we find enormous fluidity of group membership, alliance and allegiance (Charbonneau, 2019a).

These unclear borders reduce coordination among the operations, as most of military operations of Barkhane are not notified, jeopardizing blue helmets’ security (Hellquist & Sandman, 2020). Other occasions Barkhane is mandated by the UNSC to intervene if MINUSMA is under imminent threat. Nonetheless, most of the interrelations are informal, as not clearly set out in the mandate.

The field of intelligence sharing is the most relevant (Karlsrud, 2017), but only “from MINUSMA to Barkhane, not the other way around” (Hellquist & Sandman, 2020, p. 31), making the peace mission an active player in counterterrorist operations. According to Gauthier (2021), despite not being a counterterrorist operation as such, MINUSMA is “playing an active role in counterterrorist activities” (p. 849), taking part in the increasing militarization of peace operations. Furthermore, we can find some medical support to Barkhane (Hellquist & Sandman, 2020), as well as minimal cooperation among missions when deployed alongside in camp defence and reconstruction (Hellquist & Sandman, 2020), having sometimes shared camps (Moe, 2021).

We can conclude, then, that there is a certain degree of coordination, although more desired than actual, as they —unequally— share some resources and align activities. We cannot state that there is cooperation between them, as they are not “working together for jointly defined purposes” (Hellquist & Sandman, 2020, p. 19). If coordination and cooperation are already difficult up to a point within MINUSMA structure —among contributing countries, UNSC members, units, bases, etc.—, coordination and cooperation with other missions as Barkhane is far beyond, though not inexistant.

4.3. On the doctrine & the UN

Peacekeeping doctrine is not static nor agreed. Traditional conceptions based on the Charter, experience enforced by the Security Council and UN officials and experts, among others, have created a somewhat vague but shared understanding of what is peacekeeping. The holy trinity of peacekeeping —consent of the parties, impartiality, and non-use of force except in self-defence— has evolved both in theory and in practice. These principles were the common understanding of most Cold War peacekeeping operations, but Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali, in An Agenda for Peace, 1992, cleared the way for progressively nuancing them, writing the well-known phrase that peacekeeping involved the “deployment of a United Nations presence in the field, hitherto with the consent of all the parties concerned” (UN Secretary-General, 1992, par. 20, emphasis added). The report endorsed increasing and broadening peacekeeping tasks, with flexible principles; however, he separated this from peace-enforcement, calling for a heavily armed and extensive military operations apart from peacekeepers to uphold UNSC Chapter VII resolutions.

Afterwards, the Brahimi Report (UNGA & UNSC, 2000) resulting of a UN Panel on peace operations stated that: 1) consent of local parties in intra and trans-state conflicts can be manipulated; 2) impartiality rather means adherence to the principles of the Charter; and 3) the use of force should also be in defence of the mandate. But even with this maximalist interpretation, MINUSMA’s counterterrorism and counterinsurgency disrupts peacekeeping doctrine: the mission has the consent of the government, allied militias and some pro-Azawad rebels, but not the rest nor the jihadists; operational coordination with the Malian Armed Forces means siding in the conflict and abandoning impartiality; and proactive measures to counter asymmetric threats can be labelled as, indeed, active defence of the mandate —although we could argue that this concept can be used as a carte blanche for a wide range of actions—.

The Capstone Doctrine (United Nations, 2008) of the UN Secretariat Peace Operations Department followed the same path, adding that depending on the situation different types of peace operations are needed, but the UN should not engage in peace enforcement, which would entail a strategic use of force, and it should remain within the domains of peacekeeping to support cease-fires or peace agreements, or on the other hand, robust peacekeeping, which encompasses the use of force at the tactical level with host or parties’ consent. Nevertheless, MINUSMA tasks outlined in this paper blur these lines, they would involve the strategic use of force without the consent of one side of the parties, coming close to peace enforcement (Hellquist, 2020). The mission would thus be falling outside peacekeeping, which, according to Charbonneau (2017), as we have previously quoted, is “morally distinct from warfare, counterinsurgency and counterterrorism” (p. 419), because it identifies an enemy to be defeated, and peacekeepers have no enemy to destroy; and terrorist and a part of the insurgents in Mali are quite the enemy of MINUSMA, both by the wish of these non-state actors as well as by the underlying objectives of the mandate.

The High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations Report (hereafter HIPPO Report) (UNGA & UNSC, 2015) accepts that new missions are being deployed in conflict management situations in hostile settings with increasing asymmetric threats and violent extremists. In front of this, the HIPPO Report said UN peace missions are not “suited to engage in military counter-terrorism operations” (UNGA & UNSC, 2015, p. 45) due to its resources, capabilities and training, recommending the UNSC not to mandate counterterrorism, an assertion that clashes with MINUSMA’s mandate. The report does say, however, that in asymmetric environments missions ought to have the necessary capabilities and training, having “preventive and pre-emptive postures and willingness to use force tactically to protect civilians and United Nations personnel” (UNGA & UNSC, 2015, p. 45). But Karlsrud (2019) affirmed that MINUSMA’s practices suggest that it “may already have crossed the red line drawn by the HIPPO” (p. 159). Plus, the report emphasizes the necessity for a clear division of labour when a parallel counterterrorism operation is ongoing —a dubious assertion in MINUSMA’s case as we have analysed in the preceding section—. Furthermore, the panel remarks that if such a parallel force should withdraw, the peace mission should not assume the residual tasks, a matter that will have to be monitored in the current state of events where France is withdrawing Opération Barkhane.

This, being MINUSMA the first ever UN peace mission to conduct military operations against terrorist groups (Neethling, 2019) and also against insurgents, disrupts UN peacekeeping doctrine in a part of its aspects, if not interprets it in a very extensive way. Indeed, there is no consensus on UN peace operations doctrine and their modus operandi (Novosseloff, 2018), which is not consistent; actually, it is rather a normative battleground for divergent understandings and interests of all stakeholders2.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, we are going to answer the research questions posed at the beginning of the paper, which were:

A. Main question:

- 1.

In the framework of an armed conflict with the presence of terrorist and insurgent actors, has MINUSMA, as a peace operation with the basic mandate of stabilisation, carried out any counterinsurgent or counterterrorist tasks? If so, which ones?

B. Subsidiary questions:

- 1.

Do these tasks appear on the mandate or are they supervened?

- 2.

Which impacts has it had?

- 3.

Has there been coordination or cooperation with the French mission

in these tasks?

The main research question (1) should be answered positively. The mission has had direct counterterrorist and counterinsurgent tasks, and indirectly in support of the French operation and the Malian Armed Forces, although MINUSMA is not a full counterterrorist or counterinsurgent mission as such. Countering activities carried out include: intelligence, certain offensive kinetic operations, policing and law enforcement support on antiterrorism, state counterterrorism capacity-building, special operations, deterrence operations (e.g. patrols, military camps or protection of civilians), and robust and proactive retaliations against terrorists and insurgents, in addition to some cases of apprehension of terrorists.

The second hypothesis to the subsidiary question (2) on the mandate role concurs with the analysis of the resolutions: even if the tasks are not explicitly in the mandate, counterterrorism and counterinsurgency arise from it. Elements to underline include: the intentions of the Malian government in demanding the mission, the resolution’s emphasis on asymmetric threats (especially the expansive and additional resolutions), the expansion of MINUSMA in areas with asymmetric (this is, terrorist and insurgent) elements, and the call for direct countering of such groups. Likewise, the construction of an organizational structure with certain specialised counterterrorist and counterinsurgent-relevant and specific units shows an overall tacit understanding that MINUSMA should —at least partially— counter terrorists and insurgents, all under Chapter VII.

Rather than supervened, there has been an extensive interpretation of the mandate with actions falling outside traditional peacekeeping. But indeed, certain supervened responses were conducted due to the continued targeting of blue helmets and tactical needs or misdirections. Although the hypothesis for this research question viewed such an interpretation or supervened actions as a response to French interests, the extent of the paper did not allow for deep analysis on the former metropolis’ interests and reasons behind this shift. But France, as well as the Malian government, may have legitimacy reasons for its missions to push for counterterrorist and counterinsurgent involvement of the UN too.

The third subsidiary question (3) drew on the impacts. On the ground, conducting counterterrorism and counterinsurgency means having enemies, thus MINUSMA becoming a party to the conflict, being targeted by non-state actors. This loss of impartiality reduces peacekeepers’ legitimacy, fostering security risks and increasing casualties, then leaving peace prospects harder to envisage as MINUSMA sees its effectiveness, as a peace mission, lessened. These not-so-consecutive dynamics disrupt UN peacekeeping doctrine, although it is not totally outside the evolution of peace operations. This is because a sector of those proponents of robust peace missions may accept a level of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency. Nevertheless, official doctrine has never included such tasks in peacekeeping camp of action. The studied case, MINUSMA, brings about a visualization of the tension spectrum between two antagonistic but gradual camps among UN member states, scholars, UN Secretariat officials and other stakeholders: from a less engaged peacekeeping to a more engaged peace operations conception. And this tension has fluctuated over the decades, somewhat homogenized in waves, depending on the international system balance of power at the time of creation of the mission, stakes of member states, concrete ground situations and UN politics.

As said in the hypothesis, the studied elements impact on the Security Council, as for instance France would be a defender of such tasks, but Russia would be reluctant to accept these shifts, although there is a need to deepen research on this matter. Finally, it has an legitimizes pure counterterrorist forces as the regional G5 Sahel and the French Barkhane, but probably the reverse of the expected way: instead of MINUSMA legitimizing the foreign military forces, the lack of legitimacy of the French operation has infiltrated into MINUSMA.

Regarding the last research question (4), MINUSMA cooperates, though not strongly, in some aspects of the armed conflict with the French operation, notably in intelligence. In fact, it would not be wrong to label it as rather desired – by some – than actual. Also, we can affirm that the two missions do not coordinate, because they do not have a shared strategic goal nor mutually integrated modi operandi.

To sum up, this paper has validated most of its hypotheses, with nuances on certain apriorisms, having been able to argument with observations and qualitative data the essential tenets upheld in the theoretical framework.

This study has also put light on the academic gaps on the matter, which could not have been deeply considered here. Succinctly, further research is needed on the causes leading to the inclusion of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency in MINUSMA, especially regarding Security Council members’ positions, role and negotiations, which would help us understand the evolution of peacekeeping practice, and the possible future roles of such tasks in peace operations. In fact, Karlsrud (2017) already points out the political necessity of many state authorities for involving all available mechanisms, including the UN and its peace operations, in the counterterrorist struggle, because of all governments’ anxiety on terrorism. For example, in a peacekeeping summit the UK Prime Minister David Cameron mentioned terrorism as a justification for more funding, troop contributions and capabilities for blue helmets’ operations (Karlsrud, 2017). Also, further research would be interesting in the role played by the former metropolis at the UNSC, in the conceptualization of the mandate, and vis à vis the Malian government.

This focus on counterterrorism and counterinsurgency by MINUSMA and other stakeholders may help tackle the immediate threats of Mali and the Sahel – if not worsening them –, but it does not attack the root causes of the armed conflict, although multidimensionality and state-building try so. These attempts, in the words of Charbonneau (2019) are rather “vague and vacuous calls to adopt ‘holistic approaches’ or [the] never [to] forget [...] security-development nexus” (p. 31). It could be affirmed that multidimensional approaches not only of MINUSMA but of other forces as Barkhane, legitimize the parallel counterinsurgency politics of perpetual war, with the much talked-about concept of mowing the lawn, despite we cannot use this for the UN peace operation concerned. Broader counterinsurgency is busy with holistic and multidimensional approaches, and it leaves time and space for kinetic counterinsurgency to deal with the then normalized use of force (Charbonneau, 2019). Charbonneau also states that counterinsurgency politics seeks not conflict resolution but sustained engagement in the management of instability; but will MINUSMA adopt these characteristics of purer forms of counterinsurgency as the French mission?

MINUSMA’s future is uncertain, as that of Mali. MINUSMA’s Western troops have Afghanistan’s counterinsurgency and counterterrorism experience, which can lead to an increased militarization (Karlsrud, 2018). But in fact, it is the Global South troop contributors, especially Africans, who bear responsibility for the highest risk areas, and a possible increase in the studied tasks may arise the debate of the burden of the South in UN peacekeeping3 (Abdenur, 2019, p. 57). Furthermore, in 2022 the Secretary-General has suggested MINUSMA to be rehatted to an African Union force by a UNSC Chapter VII decision “to enforce peace and fight terrorism” (Radio France International [RFI], 2022), as the circumstances do not call for a peacekeeping force, Guterres stated.

Geopolitics of UN peacekeeping also encompasses acting within colonial borders. borders upon which a state-centred MINUSMA is limited impede a truly holistic approach to the armed conflict in the Sahel, as insurgents and terrorists operate transnationally (Boutellis & Tiélès, 2019).

Finally, the ultimate question is whether UN peace operations such as MINUSMA should conduct counterterrorism and/or counterinsurgency. The answer can be rationalized with rather objective data and arguments, but a normative stance on the UN peacekeeping role is always subjacent. Some scholars and stakeholders agree with the need to adapt to new challenges as terrorism and insurgency – despite not being precisely new. Others decline such shift, due to the impartiality moral claim of the doctrine, its lack of capabilities, as Charbonneau (2019), or because coalitions of the willing or multinational forces are better suited, as Karlsrud (2017). The latter two scholars, in addition, coincide in the need for only some partial countering capabilities of these threats in a defensive and preventive manner, something already taking place in a certain form.

This debate is entrenched within the doctrinal tension spectrum on peace operations, which will be even more intense in the years to come: the exit of the French Opération Barkhane, explicitly carrying out counterterrorism and counterinsurgency has allegedly pushed the new putschist government of Mali to find a substitute in the Russian Wagner private military company (Thompson et al., 2022). Furthermore, the Malian military junta has announced its withdrawal from the regional counterterrorist G5 Sahel (Africanews, 2022). But will Malian authorities be able to cover the cost to substitute France? Or will MINUSMA face a need to expand its counterterrorism and counterinsurgency tasks in the French vacuum? On the other hand, will the UN diminish or end the mission due to French pressure and confrontation with the military junta? All these contemporary questions intertwine with the studied tasks of MINUSMA in this article.

Indeed, although this paper affirms there has been and there is a place for counterterrorism and counterinsurgency in MINUSMA, paraphrasing Carl von Clausewitz, the fog of the Security Council mandate not only impedes a clear academic categorization of a peace operation, but it also carries along many of the problems the mission in Mali is currently facing, and much more in such an unstable country and region, in a no longer unipolar international and UN system.

References

Abdenur, A. E. (2019). UN Peacekeeping in a Multipolar World Order: Norms, Role Expectations, and Leadership. En C. de Coning & M. Peter (eds.), United Nations Peace Operations in a Changing Global Order (pp. 45-65). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99106-1_3

Africanews. (2022, 16 de mayo). Mali withdraws from the regional anti-jihadist force G5 Sahel. https://bit.ly/3au0AEE

Albrecht, P., Cold-Ravnkilde, S. M. y Haugegaard, R. (2016). Inequality in MINUSMA #1. African soldiers are in the firing line in Mali. Danish Institute for International Studies. https://bit.ly/3AB5pGJ

Assanvo, W., Dakono, B., Théroux-Bénoni, L. A. & Maïga, I. (2019, 10 de diciembre). Violent extremism, organised crime and local conflict in Liptako-Gourma. Institute for Security Studies – West Africa Report, 26. https://bit.ly/3NVmzBX

Bannelier, K. y Christakis, T. (2013). Under the UN Security Council’s Watchful Eyes: Military Intervention by Invitation in the Malian Conflict. Leiden Journal of International Law, 26(4), 855-874. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156513000447

Boutellis, A. y Tiélès, S. (2019). Peace Operations and Organised Crime: Still Foggy? En C. de Coning & M. Peter (eds.), United Nations Peace Operations in a Changing Global Order (pp. 169-190). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99106-1_9

Boyle, M. (2010). Do counterterrorism and counterinsurgency go together?. International Affairs, 86(2), 333-353. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40664070

Buffaloe, D. L (2006). Defining Asymmetric Warfare. The Institute of Land Warfare, 58. https://bit.ly/3nPGjMB

Charbonneau, B. (2017). Intervention in Mali: building peace between peacekeeping and counterterrorism. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 35(4), 415-431. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2017.1363383

Charbonneau, B. (2019a). Intervention as counter-insurgency politics. Conflict, Security & Development, 19(3), 309-314. https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2019.1608017

Charbonneau, B. (2019b). Faire la paix au Mali : les limites de l’acharnement contre-terroriste. Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue canadienne des études africaines, 53(3), 447-462. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2019.1666017

Cherisey, E. (2017). Desert watchers: MINUSMA’s intelligence capabilities. Jane’s Defence Industry and markets Intelligence Centre, by HIS Markit. https://bit.ly/3bXpUTK

Department of Defence. (2021). DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. https://bit.ly/3NYD0xb

Department of the Army. (2014). FM 3-24 / MCWP 3-33.5. Insurgencies and countering insurgencies. https://bit.ly/3au3Pfi

Finnemore, M. y Sikkink, K. (1998). International Norm Dynamics and Political Change. International Organization, 52(4), 887-917. https://bit.ly/3nPtNwE

Gauthier Vela, V. (2021). MINUSMA and the Militarization of UN Peacekeeping. International Peacekeeping, 28(5), 838-863. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2021.1951610

Gventer, C. W., Jones, D. M. y Smith, M. L. R. (2014). Minting New COIN. En C. Ward Gventer, D. M. Jones y M. L. R. Smith (eds.), The New Counter-insurgency Era in Critical Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137336941.0007

Hecker, M. y Tenenbaum, É. (2021). La Guerre de vingt ans: Djihadisme et contre-terrorisme au XXIe siècle. Robert Laffont.

Hellquist, E. y Sandman, T. (2020). Synergies Between Military Missions in Mali. Swedish Defence Research Agency – FOI. https://bit.ly/3yshlYD

Hüsken, T. y Klute, G. (2015). Political Orders in the Making: Emerging Forms of Political Organization from Libya to Northern Mali. African Security, 8(4), 320-337. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2015.1100502

Karlsrud, J. (2017). Towards UN counter-terrorism operations? Third World Quarterly, 38(6), 1215-1231. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1268907

Karlsrud, J. (2018). Chapter 3 New Capabilities, Tools, and Technologies. En J. Karlsrud, The UN at War (pp. 59-82). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62858-5_4

Karlsrud, J. (2019). UN Peace Operations, Terrorism, and Violent Extremism. En C. de Coning & M. Peter (eds.), United Nations Peace Operations in a Changing Global Order (pp. 153-167). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99106-1_8

Kisangani, E. (2012). The Tuaregs’ rebellions in Mali and Niger and the U.S. Global War on Terror. International Journal on World Peace, 29(1), 59-97. https://bit.ly/3yq9mLG

MINUSMA. (2017, 18 de marzo). Le Secrétaire général adjoint aux opérations de maintien de la paix Monsieur Hervé Ladsous rencontre la presse. https://bit.ly/3PaCWM0

Novosseloff, A. (2018, 19 de abril). UN Peacekeeping: Back to Basics Is Not Backwards. International Peace Institute Global Observatory. https://bit.ly/2vzd1tE

Radio France International (RFI). (2022, 6 de mayo). UN chief wants African Union force with tougher mandate for Mali. https://bit.ly/3RpAQKi

Rietjens, S. y Baudet, F. (2017). Chapter 13: Stovepiping Within Multinational Military Operations: The Case of Mali. In Information Sharing in Military Operations, eds. I. Goldenberg, J. Soeters & W.H. Dean. Springer, 201-219.

Rietjens, S. y Ruffa, C. (2019). Understanding Coherence in UN Peacekeeping: A Conceptual Framework. International Peacekeeping, 26(4), 383-407. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2019.1596742

Sandor, A. (2017). Insecurity, the Breakdown of Social Trust, and Armed Actor Governance in Central and Northern Mali. Centre FrancoPaix en resolution des conflits et missions de paix. https://bit.ly/3c2nmnx

Sieff, K. (2017, 17 de febrero). The world’s most dangerous U.N. mission. The Washington Post. https://wapo.st/3yvZHTM

Sloan, S. y Anderson, S. (2009). Historical dictionary of terrorism (3.a ed.). Scarecrow Press.

Smit, T. (2017). Multilateral peace operations and the challenges of terrorism and violent extremism. SIPRI. https://bit.ly/3yTeNUM

Snodderly, D. (2011). Peace Terms: Glossary of Terms for Conflict Management and Peacebuilding. United States Institute of Peace.

Thompson, J., Doxsee, C. y Bermúdez, J. J. S. (2022, 2 de febrero). Tracking the Arrival of Russia’s Wagner Group in Mali. CSIS – Center for Strategic & International Studies. https://bit.ly/3NZRL2W

Ucko, D. (2012). Whither counterinsurgency: The rise and fall of a divisive concept. En The Routledge Handbook of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency (pp. 77-89). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203132609-13

United Nations General Assembly & Security Council. (2000, 21 de agosto). Comprehensive review of the whole question of peacekeeping operations in all their aspects, A/55/305 – S/2000/809.

United Nations General Assembly & Security Council. (2015, de junio). Comprehensive review of the whole question of peacekeeping operations in all their aspects, Comprehensive review of special political missions & Strengthening of the United Nations system, A/70/95 – S/2015/446. Available at:

United Nations General Assembly. (2016, 12 de abril). Activities of the United Nations system in implementing the United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, Report of the Secretary-General, A/70/826.

United Nations Peacekeeping. (2021a). MINUSMA Fact Sheet. https://bit.ly/2CfCBlj

United Nations Peacekeeping. (2021b). Troop and police contributors. https://bit.ly/3yWISmB

United Nations Secretary-General. (17 June 1992). An Agenda for Peace: Preventive diplomacy, peacemaking and peace-keeping A/47/277 – S/24111. Report of the Secretary-General pursuant to the statement adopted by the Summit Meeting of the Security Council on 31 January 1992. https://bit.ly/3RqwF0z

United Nations Security Council. (2013a, 26 de marzo). Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Mali, S/2013/189. https://bit.ly/3uDZRHE

United Nations Security Council. (2013b, 25 de abril). 6052nd meeting. S/PV.6952 https://bit.ly/3nRDXNk

United Nations Security Council. (2013c, 25 de abril). Resolution 2100. S/RES/2100. https://bit.ly/3RlrtLD

United Nations Security Council. (2014, 25 de junio). Resolution 2164. S/RES/2164. https://bit.ly/3Rp3wms

United Nations Security Council. (2016, 29 de junio). Resolution 2295. S/RES/2295. https://bit.ly/3ay4DzF

United Nations Security Council. (2017, 21 de junio). Resolution 2359. S/RES/2359. https://bit.ly/3P04ELP

United Nations Security Council. (2019, 26 de marzo). Situation in Mali: Report of the Secretary-General, S/2019/262 https://bit.ly/3IvZ29N

United Nations. (2008). United Nations Peacekeeping Operations: Principles and Guidelines. UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations. https://bit.ly/2KI40Wq

United Nations. (2022). MINUSMA Deployment February 2022. Geospatial, location data for a better world. https://bit.ly/3PhzqiN

Van der Lijn, J. (2019). Assessing the Effectiveness of the United Nations Mission in Mali / MINUSMA. Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, Report 4/2019. https://bit.ly/3O2gSSG

Williams, P. D. (2008). Security Studies: An Introduction. Routledge.

Zaalberg, T. B. (2012). Counterinsurgency and peace operations. En The Routledge Handbook of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency (pp. 90-107). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203132609-14

Notes

1 Liptako-Gourma is a transnational area comprising the bordering regions of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, which has increasingly suffered from cross-border instability and security threats. For more, see Assanvo et al. (

2019).

2 For a theoretical perspective on international norm evolution – emergence, cascade and internalization–, which can be applied to peacekeeping doctrine debates, see Finnemore & Sikkink (

1998).

3 For an in-depth analysis on inequalities among MINUSMA troop contributing countries see Albrecht et al. (

2016).

Author notes

** Graduate in International Relations at Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), Cerdanyola del Vallès, Spain; with semester at Sciences Po Paris; and prospective student of the Int’l Master in Security, Intelligence and Strategic Studies at University of Glasgow, Dublin City University and Charles University of Prague. Research interests include security and armed conflicts, peace operations, internationalized civil wars, transnational insurgencies and terrorism and Sahara-Sahel region, among others. ORCID Id. 0000-0001-7354-6926. E-mail: jordi.bernal@autonoma.cat