Subjective Well-Being, Spirituality, Acculturation and Personality Traits: Understanding Argentinian Immigrants in Israel

PSOCIAL, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 48-58, 2020

Universidad de Buenos Aires

Research articles

Received: June , 22, 2020

Accepted: 29 June 2020

Abstract: There is a great migratory flow from Argentina to Israel, because there is one of the largest Jewish communities in the world today. Many judeo-argentines choose Israel as an alternative for settlement due to the political and economic instability that has rocked Argentina in recent decades. During the 2001 Argentine economic crisis, Israel saw the largest number of these Olim (Hebrew for “immigrants”) arrive in the country (Babis, 2016). A survey was recently administered among 220 Argentinians living in Israel, assessing many variables for a wide range of research inquiries. The present study is interested in the subjective well-being of immigrants related to their spirituality and the Big Five personality traits at the time of their migration, and its correlation with the acculturation trends of this sample population.

Keywords: subjective well-being, acculturation, big five personality traits, spirituality, immigration judeo-argentinian.

Introduction

According to a report by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) entitled "Migration Profile of Argentina,” in 2012 Israel was among the first destinations chosen by Argentines to emigrate, ranking 5th and representing almost 5% of the Argentine diaspora (Benencia, 2012). Migrations have taken different forms throughout history and often that creates difficult realities for migrants. There are many stressors these populations must face, including language and communication barrier, economic difficulty, sociocultural adjustment, lack of work, social exclusion or loss of family and social support, in addition to discrimination and threats that put their integrity and well-being at risk, physically and psychologically (Yoon, Lee & Goh, 2008).

Specifically, when immigration is motivated by psychological, physical or social insecurity of the original country, such as could be in these migrations to Israel from Argentina, the event can be traumatic and may negatively impact mental health (Finklestein & Solomon, 2009; Vathi & King, 2017). Many studies focus on the impact of migration on subjective well-being, while other studies have been interested in exploring additional variables that could also be involved in the relationship between migration and subjective wellbeing (Yoon, Lee & Goh, 2008). We found personality and spirituality among the most relevant variables (Emmons & Diener, 1985). Developed in the 1980s until today, the five-factor model of personality traits is the suggested measure for personality variables, consisting of: openness, conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, and extraversion (Digman, 1990; Zillig, Hemenover & Dienstbier, 2002; Rothmann & Coetzer, 2003) In addition, spirituality has been considered as the possible sixth factor of big personality traits (Piedmont, 1999).

Subjective well-being

Commonly called happiness, meaning all those experiences that make life pleasant or unpleasant, well-being is directly affected by psychological factors including personality traits or general tendencies that are reflected in many aspects of a person's life. Diener et al., (1985) used three main variables to determine subjective well-being (SWB) as a reliable measure: life satisfaction, positive affect and negative affect, which remain as the standard variables in methods determining subjective well-being and happiness to this day (Diener, 2009). With subjective well-being as the dependent variable, the present study will research its relation to personality traits and religiosity among Argentinians at the time of their immigration to Israel.

Big Five Personality Traits

Openness to experience is one of the personality traits used in the Five Factor Theory (Christensen, Cotter, & Silvia, 2019; Zillig, Hemenover & Dienstbier, 2002). Open people actively seek out new and varied experiences. Openness involves motivation, needs for variety, cognition, and understanding (McCrae & Costa Jr., 1997). Personality traits are believed to exert an important influence on social support coping for various reasons. Because our personality traits often evoke reactions from those around us, individuals respond to us in ways that are consistent with our personality. Studies surrounding the big five traits have shown that they predict perceived social support (Swickert, Hittner & Foster, 2010). In regards to openness and immigration from Argentina to Israel, openness in the individual is a possible leading factor in what guides the migration and aids acculturation. The openness level that an individual exhibits can provide a base for social cohesion once in Israel, as the migrant must interact with various new elements and obstacles in Israel. Moreover, openness entails aspects of cognitive, and other school-related abilities, presumably significant towards childhood-adult stability (Hampson & Goldberg, 2006). The personality trait, openness, has shown to be quite beneficial in its relationship with subjective well-being, with relevance to varied population groups (Mueller, Wagner, Wagner, Ram, & Gerstorf, 2019; Etxeberria, Etxebarria, Urdaneta, 2019; Steel, Schmidt & Shultz, 2008; DeNeve & Cooper, 1998).

Agreeableness is another of the five personality traits of the Five Factor Model. A person with a high level of agreeableness in a personality test is usually warm, cooperative, polite and friendly (Gordon, 2020). Studies show that on average, agreeableness and subjective well-being increase together as people mature (Mann, DeYoung, & Krueger, 2019).

Extraversion refers to a tendency to be positive, assertive, energetic, social, talkative, and warm (Penley & Tomaka, 2002; Wilt & Revelle, 2017). Both longitudinal correlational studies and week-long experimental analyses have shown a strong link between extraversion and subjective well-being, with significant and consistent results of extraversion having a positive impact on positive affect (Harris, English, Harms, Gross, & Jackson, 2017; Margolis & Lyubormirsky, 2020). Social experiences may be one channel in which extraversion is related to subjective well‐being being, by that the characteristics are often associated with assertiveness, sociability, liveliness, and positive emotionality (Watson, Stanton, Khoo, Ellickson-Larew & Stasik-O'Brien, 2019).

Neuroticism or emotional instability is a psychological trait, with the tendency to experience negative emotions such as sadness or anxiety, as well as mood swings and irrational thoughts (Costa & McCrae, 2012; Tackett, & Lahey, 2017). It contrasts emotional adjustment and stability with the general tendency to experience negative feelings that interfere with adaptation (Thompson, 2008). Low and high levels of neuroticism may be related to acculturation levels of migrants as well as positive and negative attributes to subjective well-being (Costa & McCrae, 1980).

Finally, people high in conscientiousness tend to exhibit hard-working behavior, and are generally understood as responsible (Roberts, et al., 2009). Responsibility implies feeling it is your duty to deal with what comes up, being accountable, and/or being able to act independently and make decisions without authorization (Wagele, 2015). In regards to social psychology and Argentine immigration to Israel, responsibility is an essential element that has to be established by both sides, which hold a certain mutual responsibility among them. On one hand, Israel holds the responsibility of accommodating the Argentine immigrants, protecting their rights to welfare, housing, employment and most importantly making them feel welcomed (Bayer, 2016).

Argentine immigrants, on the other hand, have certain obligations and responsibilities that they have to fulfil in Israel to ensure the social cohesion such as respecting the laws and regulations of Israel. Responsibility, therefore, is a mutual aspect on both sides and if there is a lack of responsibility then problems could emerge for the immigrants during their acculturation period. Research supports a positive correlation between positive affect in subjective well-being and the personality trait conscientiousness (Gore et al., 2014).

Spirituality and Religion

Following a widely cited, controlled psychological study, there is an argument to consider spirituality as the potential sixth personality trait in the aforementioned Five-Factor Model or Big Five Personality Traits (Piedmont, 1999). Spirituality is a term abstracted from religion, involving “a relationship with someone or something beyond ourselves, someone or something that sustains and comforts us, guiding our decision making, forgiving our imperfections, and celebrating our journey through life” (Spaniol, 2002). Spirituality, therefore, can be a positive reinforcement of one's mental health. Being that immigration to Israel is often tied to spirituality or religion, it can be related to positive and negative coping mechanisms for post-migration forces (Rosmarin et al., 2017). Considering that spirituality may supply a strong feeling of connectedness with a broader life force, other people and environment, it could help with traumatic or daunting experiences that immigration could stimulate (Lee-Fong, 2020).

Israel being a religious nation, spirituality is intrinsically linked to the “Aliyah” migration to Israel. These immigrating “Olim” must prove a Jewish bloodline or behold an adequate conversion status to the religion in order to immigrate under the Jewish Law of Return (State of Israel, 2003). Considering that the Jewish community in Argentina is a closely connected interwoven group, often functioning together with the shared characteristic of being Jewish, the sense of community is strong: Argentina ranks at the sixth largest Jewish population in the world as of 2019 (Jewish Population of the World, 2020). According to the Jewish Virtual Library, a project by Ace, 69,718 Argentinians have emigrated from 1948 until 2018 (Total Immigration to Israel by Select Country by Year, 2020). The factors of religion and spirituality in relation to the individual immigrating may prove interesting in our correlational analysis.

In this study, we will analyze a correlation of variables that may contribute to the immigrants’ ability to cope with adversity and the capacity to develop skills in stressful situations: personality, spirituality and subjective well-being (Rosmarin et al., 2017).

Method

Design

It was conducted as a non- experimental, cross-sectional study (Montero & León, 2007).

Participants

The sample was composed of 220 argentinian immigrants (115 women and 105 men) living in Israel, and the questions were referring to the moment of the subjects’ migration. All participants were between the ages of 18 to 77 years old and voluntarily partook in the study.

Materials

A test battery was administered from the University of Buenos Aires, and participants were gathered via Facebook audience analytics. Translation from Spanish to English was aided by Google Translate and affirmed by the researchers of this study.

Measures

The data was collected through a self-administered evaluation instrument. It was integrated by the following techniques:

Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments Scale

ASPIRES (Piedmont, 2010) is a 35-item self-report questionnaire that measures Religious Sentiments and Spiritual Transcendence. Religious Sentiment consists of two dimensions: Religious Involvement (e.g. “How often do you pray?” / “¿Cuán seguido reza?”) and Religious Crisis (e.g.” I feel that God is punishing me” / “Siento que Dios me está castigando”). Spiritual Transcendence includes three further dimensions: Prayer Fulfillment (e.g. “I find inner strength and/or peace from my prayers or meditations'' / “Encuentro fuerza interior y/o paz en mis rezos y/o meditaciones”), Universality (e.g. “I feel that on a higher level all of us share a common bond” / ”Siento que en un nivel superior todos compartimos un vínculo común”) and Connectedness (“Although they are dead, memories and thoughts of some of my relatives continue to influence my current life” / “Aunque ya fallecidos, recuerdos y pensamientos de algunos de mis parientes continúan influenciando mivida actual”). The version was adapted to the Argentine context by Simkin (2017).

Mini International Personality Ítem Pool

Mini-IPIP (Donnellan, 2006) is a 20 item questionnaire in order to access the big 5 personality traits; (1) Openness to Experience (e.g. "I am not interested in abstract ideas"/ “No me interesan las ideas abstractas), (2) Conscientiousness (e.g. "I am somewhat disorderly"/ “Soy algo desordenado”), (3) Extraversion (e.g. “I don't like to attract attention”/ “No me gusta llamar la atención”); (4) Agreeableness (e.g. "I am not very interested in the problems of others"/ “no me interesan los problemas de los demás”), and (5) Neuroticism or Emotional Stability (e.g. "I rarely feel sad"/”Rara vez me siento triste”). The scale has a Likert-type response format with five anchors of response depending on the degree of agreement of the participants, with 1 being "Completely agree" and 5 "Completely disagree". The version was adapted to the Argentine context by Simkin, Borchardt Duter and Azzollini (2020).

Affect Balance Scale

EBA (Warr et al., 1983) is a questionnaire self-administered of 18 items, of which 10 belong to the original scale (Bradburn, 1969), and eight to the additions by Warr et al., (1983) in order to strengthen the Bradburn scale. The instrument directly evaluates both experimentation of positive affect (“Have you been happy?" / “¿Te has sentido feliz?”) as negative ("Have you felt like crying?" / ¿Te has sentido a punto de llorar?”). The items present a response format Likert type with five anchors response depending on the degree of agreement of participants ranging from 1 (never) and 5 (generally). The version was adapted to the Argentine context by Simkin, Olivera and Azzollini (2016).

Satisfaction with Life Scale

SWLS (Diener et al., 1985) is a 5-item scale designed to be a cognitive measure evaluation of an individual’s life satisfaction. Participants specify how much they agree or disagree with each of the five items using a seven-point Likert scale. The scale ranges from 7 (strongly agrees) to 1 (strongly disagrees). The scale is designed to assess individual’s satisfaction with life as a whole rather than individual specific life domains. The version was adapted to the Argentine context by Moyano, Martinez-Tais & Muñoz (2013).

Acculturation

Acculturation model developed by John Berry (1994; 2003; 2006) suggests four central categories: Assimilation (drop the old culture to assimilate completely to the new culture), Rejection (keep the old culture and not incorporate any of the new one), Integration (integrate the aspects of the old culture with aspects of the new one), and Marginalization (feel they don’t belong in either of the cultures). In order to measure acculturation in the present study, four items were written for the participants to answer. In the respective sequence to the Berry model described above, those items were: 1) "I feel more Argentine than Israeli"/"Me siento más argentino que israelí"; 2) "I feel more Israeli than Argentine"/"Me siento más israelí que argentino"; 3) "I feel that I am as Argentine as Israeli"/"Siento que soy tan argentino como israelí"; 4) "I feel that I do not fully belong to either Argentina or Israel"/"Siento que no pertenezco por completo ni a Argentina ni a Israel".

Results

The survey results underwent a correlational analysis to associate significance between variables (Table 1) using statistic software SPSS version 23.

Negative affect shows inverse correlation with life satisfaction, positive affect, conscientiousness, assimilation; and direct correlation with neuroticism and rejection. Positive affect correlates directly with life satisfaction, extroversion, agreeableness, spirituality, assimilation, and integration; and inversely with neuroticism, rejection and marginalization.

Life satisfaction shows inverse correlation with negative affect, neuroticism, rejection and marginalization; and a positive correlation with positive affect, extroversion, agreeableness, spirituality and assimilation.

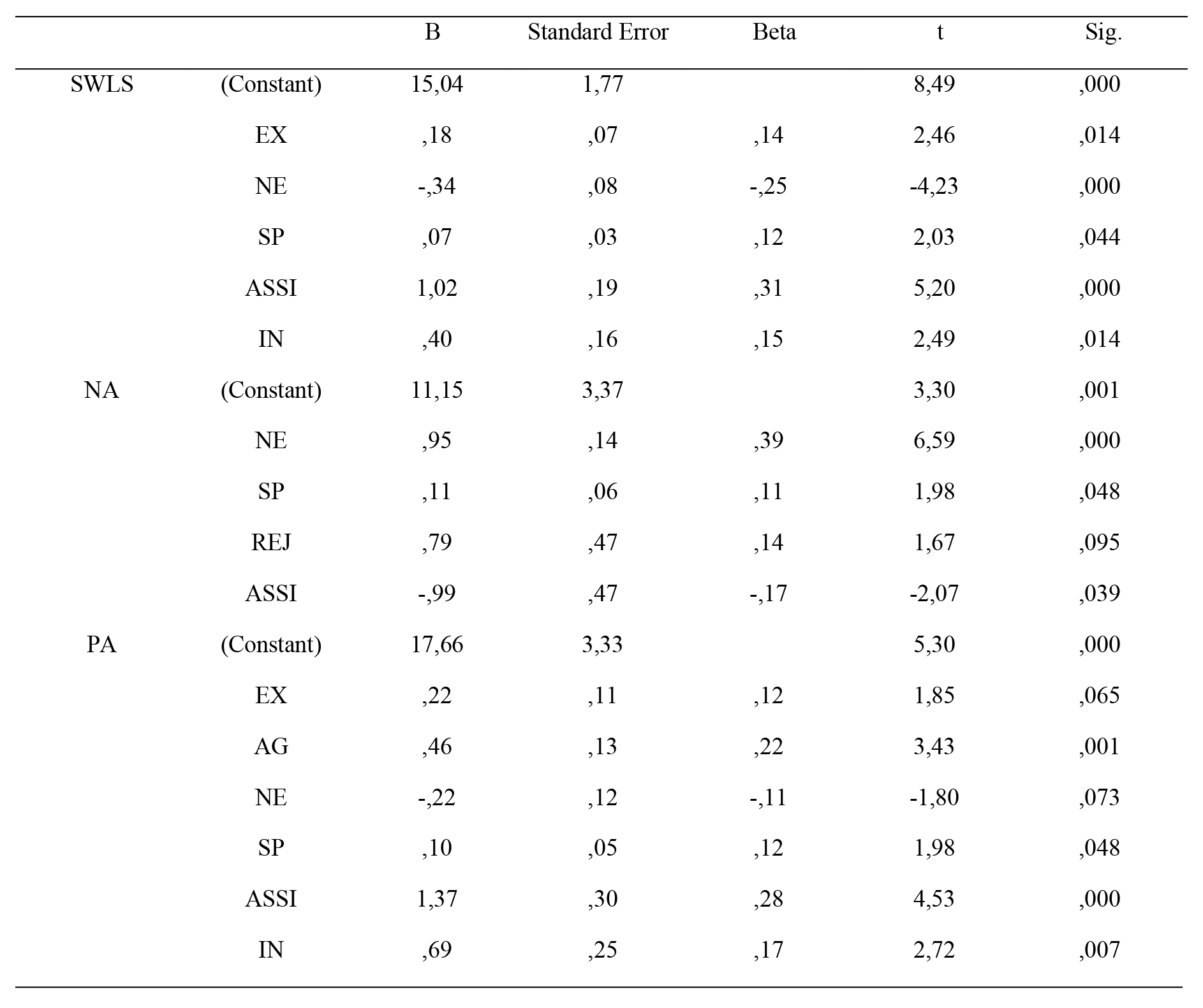

Three regression models subsequently show the different variables that may relate, or have influence on, life satisfaction, negative affect and positive affect. A regression analysis with backward method addressed the following associations (Table 2).

According to life satisfaction model: extroversion (β= .180; sig .014), neuroticism (β= -.344; sig .000), spirituality (β= .070; sig .044), assimilation (β= 1.025; sig .000) and integration (β= .409; sig .014) affect life satisfaction.

By negative affect model: neuroticism (B= .959; sig .000), spirituality (B= .118; sig .048), rejection (B= .795; sig .095) and assimilation (B= -.990; sig .039) affect negative affect.

And finally, depending on positive affect model: extroversion (B= .221; sig .065), agreeableness (B= .463; sig .001), neuroticism (B= -.229; sig .073), spirituality (B= .105; sig .048), assimilation (B= 1.379; sig .000) and integration (B= .691; sig .007) affect positive affect.

Discussion

The results of the general literature on happiness and subjective well-being give very useful clues to study the well-being of migrants, however, at the same time they indicate very significant limitations, where the happiness functions of this group may differ from those of the population in general for various different reasons (Hendriks and Bartram, 2018). Firstly, migrants are a self-selected group and as such may have their own unique characteristics. Likewise, the happiness of migrants also depends on factors that do not affect non-migrants, such as acculturation, discrimination and the social skills necessary to rebuild a social and economic network in a new environment and the conditions of their country of origin (Panzeri, 2019). On the individual level, immigrants vary in several specifications but they also share a number of commonalities. These small but influential differences play a big role in the overall satisfaction with life, happiness and well-being (Heizmann and Böhnke, 2018).

In contrast, multicultural groups are likely to consider different criteria relevant when judging the success of their society since they have different sets of values. Different cultures living in one place and their subjective definitions of a concept like well-being can be a perfect example of the extent to which people in each society are actualizing the values that they hold in high regard (Diener, 2009).

A recently published article in the Frontiers Magazine studies the relation between Spirituality and Psychological Well-Being; however, it did not consider the Big Five Factors of Personality (Simkin, 2020). For that reason, the present study incorporates variables such as neuroticism, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness and looks further into how they are related to life satisfaction, negative affect and positive affect in the lives of the Argentine population that has settled in Israel. Conversely, studies have shown that personality traits play a role in affecting attitudes towards immigration and immigrants, relating to overall important national concerns such as diversity of cultural backgrounds and prejudice (Dinesen, Klemmensen & Nørgaard, 2014)

Limitations of this study include a small and therefore non-representative sample. The omission of certain demographic variables could have affected the correlations and regressions, such as age, sex, relationships, offspring, socio-economic status and more. This study omitted those variables in order to simplify the process. Finally, the happiness of migrants may depend to a greater extent on the specific reasons that motivated their transfer whether religious, political, socio-economic or other. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that migrants, even if they improve their material living conditions, experience greater subjective well-being after migration (Hendriks and Bartram, 2018). Further studies could include more constant demographic variables to determine any relation with well-being of Argentinian immigrants in Israel. The present study could be referenced as a model for similar research that seeks to study populations in other parts of the world.

References

Babis, D. (2016). The paradox of integration and isolation within immigrant organisations: the case of a Latin American Association in Israel. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(13), 2226–2243. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1166939

Bayer, Y. (2016). Struggling to belong: the collective memory of immigrants from Argentina in Israel. Retrived in https://ssrn.com/abstract=3217646 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3217646

Benencia, R. (2012) Perfil Migratorio de Argentina. Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. p. 42.

Berry, J. (1994). Acculturation and psychological adaptation: An overview. In A. M. Bouvy, F. J. R. van de Vijver, P. Boski, & P. G. Schmitz (Eds.). Journeys into cross-cultural psychology (pp. 129–141). Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers.

Berry, J. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. Balls Organista, & G. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 17–37). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10472-004

Berry, J., Phinney, J., Sam, D., & Vedder, P. (2006). Immigrant youth: acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 55(3), 303–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00256.x

Bradburn, N. (1969). The structure of psychological well-being. Aldine. http://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.19640050205

Christensen, A., Cotter, K., & Silvia, P. (2019). Reopening openness to experience: A network analysis of four openness to experience inventories. Journal of Personality Assessment, 101(6), 574-588.

Costa, P., & McCrae, R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(4), 668–678. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.38.4.668

Costa, P. & McCrae, R. (2012). The five-factor model, five-factor theory, and interpersonal psychology. In L. M. Horowitz & S. Strack (Eds.). Handbook of Interpersonal Psychology: Theory, Research, Assessment, and Therapeutic Interventions (pp. 91-104). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118001868.ch6

De Neve, K., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 197–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Diener, E. (2009). The science of well-being. Springer

Digman, J. (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology, 41, 417–440.

Dinesen, P. T., Klemmensen, R., & Nørgaard, A. S. (2016). Attitudes toward immigration: The role of personal predispositions. Political Psychology, 37(1), 55-72.

Donnellan, M. B., Oswald, F. L., Baird, B. M., & Lucas, R. E. (2006). The mini-IPIP scales: tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18(2), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192

Emmons, R., & Diener, E. (1985). Personality correlates of subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 11(1), 89–97. https://doiorg.rproxy.tau.ac.il/10.1177/0146167285111008

Etxeberria, I., Etxebarria, I., & Urdaneta, E. (2019). Subjective well-being among the oldest old: The role of personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 146, 209–216. https://doi-org.rproxy.tau.ac.il/10.1016/j.paid.2018.04.042

Finklestein, M., & Solomon, Z. (2009). Cumulative trauma, PTSD and dissociation among Ethiopian refugees in Israel. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 10(1), 38-56.

Gordon, S. (2020). Understanding agreeableness and its impact on your behavior. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.verywellmind.com/how-agreeableness-affects-your-behavior-4843762

Gore, J., Davis, T., Spaeth, G., Bauer, A., Loveland, J., & Palmer, J. (2014). Subjective well-being predictors of academic citizenship behaviour. Psychological Studies, 59(3), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-014-0235-0

Hampson, S., & Goldberg, L. (2006). A first large cohort study of personality trait stability over the 40 years between elementary school and midlife. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 763-779. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.763

Harris, K., English, T., Harms, P., Gross, J., & Jackson, J. (2017). Why are Extraverts more satisfied? personality, social experiences, and subjective well‐being in college. European Journal of Personality, 31(2), 170-186.

Heizmann, B., & Böhnke, P. (2019). Immigrant life satisfaction in Europe: the role of social and symbolic boundaries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(7), 1027-1050.

Hendriks, M. & Bartram, D. (2019). Bringing happiness into the study of migration and its consequences: what, why, and how? Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 17(3), 279-298.

Jewish Virtual Library. (2020). Jewish Population of the World. Retrieved 20 July 2020, from https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jewish-population-of-the-world

Lee-Fong, G. (2020). The relationship between spiritual intelligence and psychological well-being in refugees. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 81, 3-8.

Mann, F. D., DeYoung, C. G., & Krueger, R. F. (2019). Patterns of cumulative continuity and maturity in personality and well-being: Evidence from a large longitudinal sample of adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 109737.

Margolis, S., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2020). Experimental manipulation of extraverted and introverted behavior and its effects on well-being. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 149(4), 719–731. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000668

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1997). Conceptions and correlates of openness to experience. In R. Hogan, J. A. Johnson, & S. R. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology (pp. 825–847). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012134645-4/50032-9

Montero, I., & León, O. (2007). A guide for naming research studies in Psychology. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 7(3), 847–862.

Moyano, N. C., Tais, M. M., & Muñoz, M. P. (2013). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida de Diener. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 22(2), 161-168.

Mueller, S., Wagner, J., Wagner, G., Ram, N., & Gerstorf, D. (2019). How far reaches the power of personality? Personality predictors of terminal decline in well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(4), 634–650. https://doi-org.rproxy.tau.ac.il/10.1037/pspp0000184

Panzeri, R. (2019). Migration and well-being: the importance of a narrative perspective. International Journal of Migration Studies, 8 (2), 252-286.

Penley, J., & Tomaka, J. (2002). Associations among the Big Five, emotional responses, and coping with acute stress. Personality and individual differences, 32(7), 1215-1228.

Piedmont, R. (1999). Does spirituality represent the sixth factor of personality? Spiritual transcendence and the five‐factor model. Journal of personality, 67(6), 985-1013.

Piedmont, R. L. (2010). Assessment of spirituality and religious sentiments technical manual (2nd ed.). Author.

Roberts, B.; Jackson, J.; Fayard, J.; Edmonds, G.; Meints, J. (2009). Conscientiousness. In Mark R. Leary, & Rick H. Hoyle (ed.). Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior (pp. 257–273). The Guildford Press. ISBN 978-1-59385-647-2.

Rosmarin, D. H., Pirutinsky, S., Carp, S., Appel, M., & Kor, A. (2017). Religious coping across a spectrum of religious involvement among Jews. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 9(S1), S96.

Rothmann, S., & Coetzer, E. P. (2003). The big five personality dimensions and job performance. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 29(1), 68-74.

Simkin, H. (2017). Adaptación y Validación al Español de la Escala de Evaluación de Espiritualidad y Sentimientos Religiosos (ASPIRES): la trascendencia espiritual en el modelo de los cinco factores. Universitas Psychologica, 16(2), 1-12.

Simkin, H. (2020). The Centrality of Events, Religion, Spirituality, and Subjective Well-Being in Latin American Jewish Immigrants in Israel. Front. Psychol. 11, 576402. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.576402

Simkin, H., Borchardt Duter, L., & Azzollini, S. (2020). Evidencias de validez del Compendio Internacional de Ítems de Personalidad Abreviado. Liberabit: Revista Peruana de Psicología, 26(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2020.v26n1.02

Simkin, H., Olivera, M., & Azzollini, S. (2016). Validación argentina de la Escala de Balance Afectivo. Revista de psicología, 25(2), 1-17.

Spaniol, L. (2002). Spirituality and connectedness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(4), 321–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095006

State of Israel (2003). The Knesset: Laws. Retrieved July 2020. The Law of Return

Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134(1), 138–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.138

Swickert, R.., Hittner, J., & Foster, A. (2010). Big Five traits interact to predict perceived social support. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(6), 736-741.

Tackett, J., & Lahey, B. (2017). Neuroticism. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.). The Oxford handbook of the Five Factor Model (pp. 39–56). Oxford University Press.

Thompson, E.R. (2008). Development and validation of an international english big-five mini-markers. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(6), 542–548.

Jewish Virtual Library. (2020). Total immigration to Israel by select country by year. Retrieved 20 July 2020, from https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/total-immigration-to-israel-by-country-per-year

Vathi, Z., & King, R. (Eds.). (2017). Return migration and psychosocial wellbeing: discourses, policy-making and outcomes for migrants and their families. Taylor & Francis.

Wagele, E. (2015). Nine Kinds of Responsibility. Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/the-career-within-you/201508/nine-kinds-responsibility

Warr, P., Barter, J., & Brownbridge, G. (1983). On the independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(3), 644-651. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.3.644

Watson, D., Stanton, K., Khoo, S., Ellickson-Larew, S., & Stasik-O'Brien, S. (2019). Extraversion and psychopathology: A multilevel hierarchical review. Journal Of Research In Personality, 81, 1-10.

Wilt, J., & Revelle, W. (2017). Extraversion. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Five-Factor Model (pp. 57–81). Oxford University Press.

Yoon, E., Lee, R., & Goh, M. (2008). Acculturation, social connectedness, and subjective well-being. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14(3), 246–255. https://doi-org.rproxy.tau.ac.il/10.1037/1099-9809.14.3.246

Zillig, L., Hemenover, S., & Dienstbier, R. (2002). What do we assess when we assess a Big 5 trait? A content analysis of the affective, behavioral, and cognitive processes represented in Big 5 personality inventories. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(6), 847-858.