Abstract: Nostalgia has a solid presence in marketing. Studies have shown that nostalgic marketing strategy could be a powerful tool to market some goods and services. It has been seen that nostalgic marketing campaigns are becoming a preferred way of making the most out of brand equity possessed by old products, logos, and packaging. This study examines the prospects of nostalgia marketing for the music market and probes the level of nostalgia among various sets of personal characteristics. The study has applied a two-stage stratified sampling method. Seven strata have been identified based on respondents’ occupation, then a random sampling technique for final sample selection has been applied. Results suggested that nostalgia proneness varies among different groups of people. The study also found a strong association between nostalgia proneness and some individual and group characteristics. The study is thus telling decision-makers to seriously look into the nostalgia fact so that opportunities could be exploited. As a future research direction, it is advised to conduct multiple rigorous studies to comprehend the issue from varied perspectives.

Keywords: Nostalgia,Retromania,Music,Nostalgic Behavior,Nostalgic Marketing.

Resumo: A nostalgia tem uma presença sólida no marketing. Estudos têm mostrado que uma estratégia de marketing nostálgico pode ser uma ferramenta poderosa para comercializar alguns bens e serviços. Foi visto que as campanhas de marketing nostálgicos estão se tornando a forma preferida de aproveitar ao máximo o valor da marca possuído por produtos, logotipos e embalagens antigas. Este estudo examina as perspectivas do marketing de nostalgia para o mercado musical e investiga o nível de nostalgia entre vários conjuntos de características pessoais. O estudo aplicou um método de amostragem estratificada em dois estágios. Sete estratos foram identificados com base na ocupação dos entrevistados, em seguida, uma técnica de amostragem aleatória para a seleção da amostra final foi aplicada. Os resultados sugeriram que a tendência à nostalgia varia entre diferentes grupos de pessoas. O estudo também encontrou uma forte associação entre a tendência à nostalgia e algumas características individuais e de grupo. O estudo está, portanto, dizendo aos tomadores de decisão para olhar seriamente para o fato da nostalgia para que as oportunidades possam ser exploradas. Como direção de pesquisas futuras, é aconselhável realizar vários estudos rigorosos para compreender o assunto de perspectivas variadas.

Palavras-chave: Nostalgia, Retromania, Música, Comportamento Nostálgico, Marketing Nostálgico.

Artigos

Nostalgia Marketing: Examining music retromania

Marketing de nostalgia: Examinando a retromania da música

Received: 17 October 2020

Accepted: 16 March 2021

The term ‘nostalgia’ was introduced in 1688 by Johannes Hofer, who entitled his doctoral dissertation at the University of Basle, Dissertatio medica de nostalgia (Fuentenebro de Diego & Valiente Ots, 2014). The word was coined from the Greek nostos (return) and algos (pain) (Prete, 2001). As Havlena and Holak (1991) suggested, however, recently nostalgia has received increased attention from marketers and advertisers.

Nostalgia begins when individuals experience some kind of fondness about their past. The fondness could be for tangible (e.g., social groups, possessions) and intangible (e.g., olfactory cues, music) stimulus of that period (Sierra & McQuitty, 2007). In today’s marketplace, it is easy to witness firms trying to use nostalgia to address a growing desire by consumers to recapture part of their past (idealized past) through nostalgic consumption (Cui, 2015). As Friedman (2016) stated, aligning marketing strategies with emotion has already proven to be successful, but tapping into fond memories can be an invaluable tactic. Nowadays, as Friedman (2016) clinched, from fast food and breakfast cereals to gaming systems and everything in between, brands are engaging through retro roots.

When it comes to music, the presence of nostalgia is even more strong. Certain music productions can signal and reinforce consumers’ self-identity, which results in one’s life experiences (Reed, Forehand, Puntoni, & Warlop, 2012). Furthermore, as Barrett et al. (2010) described, nostalgia is associated with both joy and sadness, whereas non-nostalgic and nonautobiographical experiences were associated with irritation. Marchegiani and Phau (2012) also suggested that marketing practitioners are better informed when including nostalgic orientated music because in most the customers a predisposition to personal nostalgia is found as a salient response; hence this fact in the customer's attitude provides continued support for the importance of music in advertising. Despite there are plenty of empirical evidence on the concept; it is not common to see the use of the behavior for marketing strategies especially for products like music. Therefore, this study is aimed to fill this gap.

As established in many of the previous studies, the feelings of warmth, happiness, and security that may be evoked when someone thinks about the past could be used as a powerful marketing tool. Like other groups of consumers, music listeners have a strong association with their “good old days”. Therefore, it is always good to understand how and when the feeling emerges. For consumers, the memory for “good old days” can be triggered by many reasons, including music made by old instruments, lyrics, and styles; advertising messages made from classical music and images; CD packages designed with old pictures and posters designed based on an old style. All these can easily stir-up music customers’ nostalgic behavior. Once the behavior emerged, the subsequent buying decisions could be positively enthused; which is of course one of the times to exploit people’s nostalgic consumption behavior; this is especially correct when customers found themselves in an unpleasant present and uncertain future. As a response to the increasing customer's nostalgic behavior, numerous products and packages from the past or inspired by the past have been reintroduced. Correspondingly, the adoption and diffusion process for those amended products is fast. This and many other trends can be an indication for the potential and existential influence of nostalgia to affect customers buying behavior. To exploit this opportunity, marketers shall scientifically explore the level of nostalgic behavior among music listeners.

In the study, the following research questions are inquired:

· What is the level of nostalgic behavior among music listeners?

· In what way are nostalgia proneness and selected characteristics interacting?

· What are the prospects for nostalgic marketing campaigns in the music market?

The literal meaning of the word nostalgia is the pain caused by taking flight home (Cui, 2015). It wasn’t until the middle of the twentieth century that the term lost its medical association and came to mean “a sentimental longing for the past” or being bittersweet, simultaneously calling forth both happy and sad emotions (Zhou et al., 2012).

As Fox and Davis (1981) suggested, there are two major categories of nostalgia, personal and historical. Personal nostalgia involves a “personally remembered past” while historical nostalgia involves time before the person was born. Personal nostalgia is mostly affected by the individual biographical experience, such as a memory of childhood and certain particular events. On the contrary, historical nostalgia emphasizes the collective memory of a cultural group or human beings, and some historical events merged in nostalgia are not directly experienced by individuals. Baker and Kennedy (1994) have also introduced a third type of nostalgia – “collective nostalgia,” which involves a shared longing for past by “a culture, a generation, or a nation”. People like Kozinets (2004) are arguing that personal and communal nostalgia are closely related in marketing because brands form connections with both individuals and larger communities or past events.

Consumer nostalgia is a passion for people, places, and things from the past. And these things were common (popular, trendy, or spreading) in people when they were young (early adulthood, adolescence, childhood, or even before birth)(Cui, 2015). Holak, Havlena and Matveev (2006) studied the conceptual structure of consumer nostalgia, and suggested the four variants; personal nostalgia, interpersonal nostalgia, cultural nostalgia, and virtual nostalgia, based on books, video materials, and other non-direct experience of a group. This finding tells all of us that individual and group nostalgia can encourage consumers towards a richer emotional experience.

A study in Taiwan by Chen, Yeh and Huan (2014) found that nostalgia has both direct and indirect impacts on consumption intention; consumption affected by nostalgia varies depending on the individual, and younger customers' predisposition. Ju, Kim, Chang and Bluck (2016) finds that nostalgic past-focused advertisements (as compared to present-focused advertisements) elicited higher perceived self-continuity which led to more favorable ratings and greater intent to purchase the product. These effects held up regardless of product type. As Hunt and Johns (2013) stated, nostalgia is an effective tool for developing brand and advertising images for the hospitality industry.

Even though there are debates as to whether nostalgic feelings are positive or negative, marketers are interested only to view from positive perspectives. Vignolles and Pichon (2014) suggest that nostalgic food consumption is rather related to positive emotions. Pascal, Sprott, and Muehling (2002) suggested that advertisers should emphasize the positive perspective of nostalgia to avoid negative emotions caused by the inability of returning to the past. Results of a study by Sierra and Mcquitty (2007) show that consumers' intentions to purchase nostalgic products are simultaneously affected by a yearning for and attitudes about the past.

Advertising is assumed to be the most appropriate means to practice nostalgic marketing. Pascal et al. (2002) studied the effectiveness of nostalgic advertising and they found that nostalgic advertisements are more effective in making customers listen and evaluate the message carefully. Further nostalgic cues used in advertising work as stimuli to trigger the listener’s positive memory. As Marchegiani and Phau (2012) stated; music with only a nostalgic theme does not enhance any of the nostalgic types under the nostalgic conditions; hence it is advised to introduce music to the intended non-nostalgic condition to increases personal nostalgic reactions and brand/message-related thoughts.

This happens when designers taking advantage of people’s memory of the past. It is consciously creating a “sense of history” or “original sense” on the product packaging. These packaging always use natural materials, and the decoration is rough simply, to present a unique historical flavor (Cui, 2015). Nostalgic packaging elicits symbolic meanings and acts as an important cue for consumers to infer the credibility of the products when no other product and brand information is available. According to Underwood (2003), for most of the packaged consumer products, packaging, advertising, and other promotional tools are more important in attracting consumer’s primary attention and forming the product/brand impression than in cultivating brand loyalty.

Nostalgia tinged marketing strategies can also be used in-store and restaurant decoration. Hamilton and Wagner (2014) suggested that by employing nostalgia cues through product, ritual, and aesthetics, an idealized store decoration can be constructed emphasizing belonging and sharing. For example, it is possible for the small business owner to effectively transform a contemporary tea room into a cultural room without replicating tradition. Similar to nostalgic packaging, wall and other house decorations can be used as a stimulus to trigger nostalgic feelings.

As Schindler and Holbrook (2003) stated, later in life people tend to be most nostalgic for things that were popular in their late teens and early twenties hence nostalgia proneness is dependent on age, gender, and other demographic factors; Further, a study by Stem (1992) found that people are more affected by the past when they are found in an unpleasant current and uncertain future. Moreover, as Sedikides and Wildschut (2018) argued, situations like unemployment (both permanent and temporary), marital status, religion, and our residence can all affect the proneness to nostalgia. Possible explanations for this phenomenon include the fact that exposure to products such as music may be highest during “good times of life” and linked to a stage of life with mostly positive emotions.

Schindler and Holbrook (2003) measured the influence of demographic factors to influence nostalgic feelings in a variety of products, like the peak nostalgia age for music, movie stars, fashion models, and classic cars, and the finding shows positive relationships. Another study by Friedman (2016) suggests that when using nostalgia in marketing to millennials, historical nostalgia will be more effective than personal nostalgia since millennials have not yet reached an age when personal nostalgia becomes significant.

Many millennials are in that formative stage of nostalgia (late teens and early twenties) which will shape their taste in products for the rest of their lives but do not feel intense personal nostalgia for products popular during their childhood. This conclusion supports the impact of demographic factors like age on nostalgia proneness. A retro brand’s heritage can also serve as a proxy for experience, which can be compelling in a retail environment that is overwhelmed by thousands of new product launches every year (Triantafillidou & Siomkos, 2014). Schindler and Holbrook (2003) argued, that nostalgia proneness is measurable; suggesting that some people are more prone to nostalgic emotions than others.

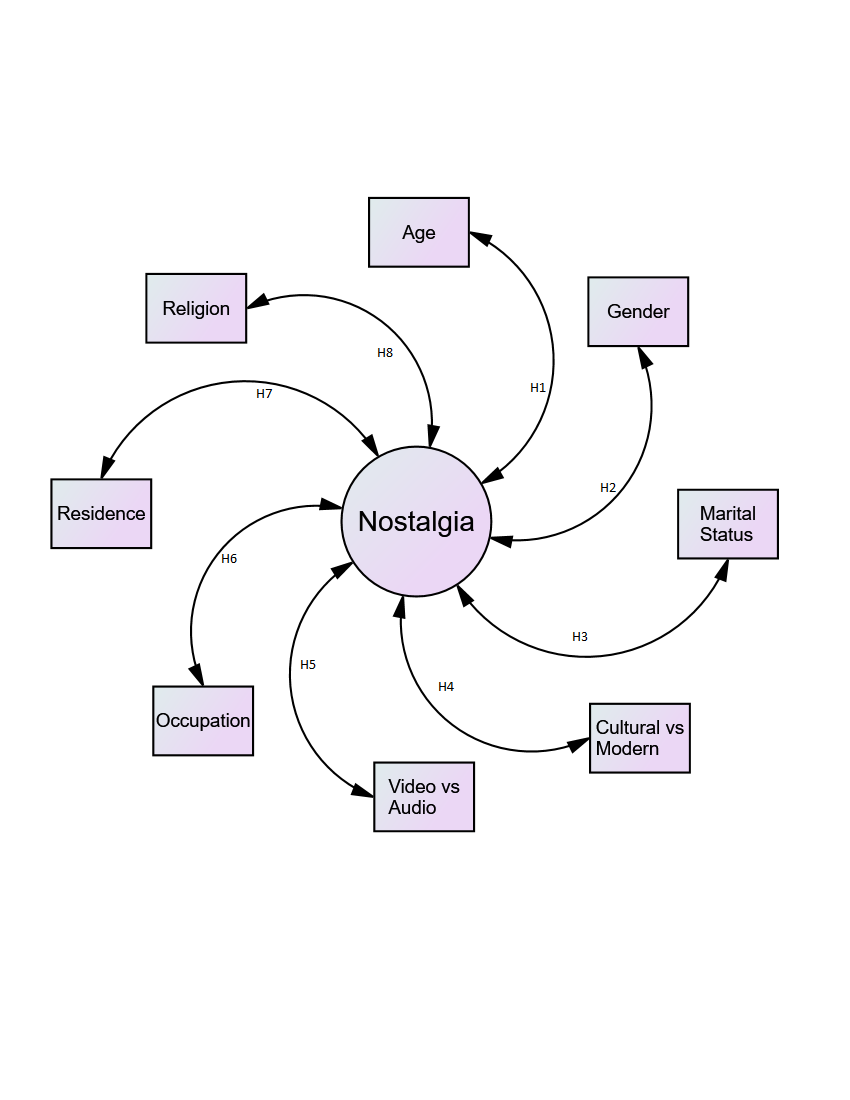

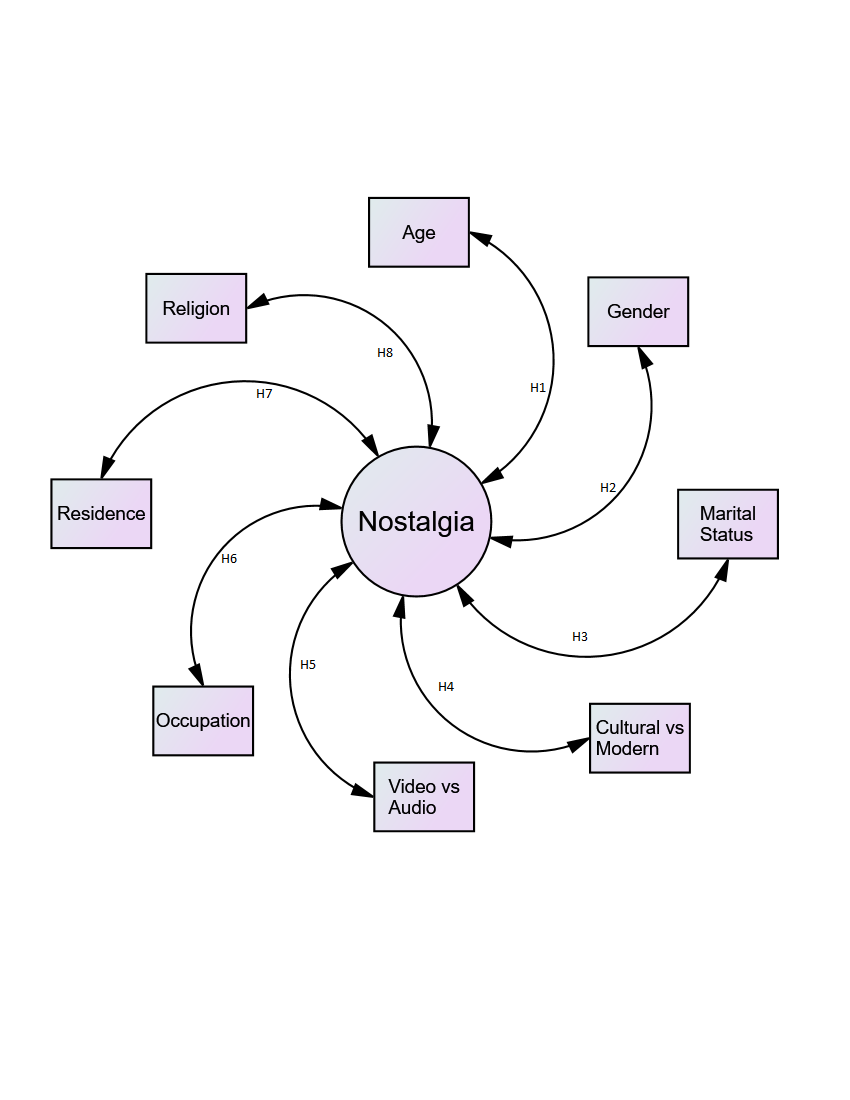

The study is attracted to examine the prospects of nostalgia marketing in the music industry. It is convincing that examining the association between nostalgia proneness and some of the important characteristics of participants could be the best way to judge the marketing potential of the nostalgic campaign. Based on the findings and suggestions made by a handful of scholars, the following theoretical framework is developed. Age, gender, marital status, music preferences, occupation, residence, and religion are treated as independent variables; whereas nostalgia proneness is taken as a dependent variable. The connecting arrows in the model are intentionally made to be double arrows; this is because the study is examining association rather than a causal relationship. Eight hypotheses are extracted from the framework. Literature from old to new, simple to complex, and subject related to unrelated are investigated.

Based on the results of prior studies, the following hypotheses are suggested:

H1: nostalgia proneness and age are associated

H2: nostalgia proneness and gender are associated

H3: nostalgia proneness and marital status are associated

H4: nostalgia proneness and cultural and modern music preference are associated

H5: nostalgia proneness and watching/listing music preference are associated

H6: nostalgia proneness and occupation are associated

H7: nostalgia proneness and residence of people are associated

H8: nostalgia proneness and religion are associated

The study applied the objectivism, and positivism ontological and epistemological approaches respectively. Consequently, the deductive/quantitative approach is used. Thus, the objective is going to be describing the nostalgic characteristics of music customers, and the prospects for a nostalgic marketing strategy. In this study since the quantitative research approach is utilized, the data and eventually results are analyzed and presented solely through the use of a quantitative method.

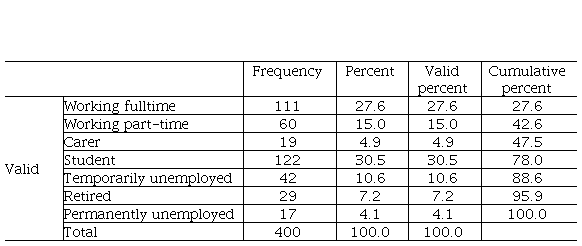

For the reason that the population is infinite, the size of participants is meant to be as high as 400. The subjects have been selected based on a convenience sampling method. Therefore, after making seven stratums based on the occupation of respondents; (working fulltime, working part-time, carer, university students, temporarily unemployed, retired, permanently unemployed) questionnaires are distributed for nonrandomly selected participants. The reason for choosing occupation as a stratification base is because it is good to exhaustively embrace every section of the society and it is clear that everybody in the society has some occupation, this reality can make this decision very much demonstrative.

The instrument for measuring nostalgia proneness is adopted from (Holbrook, 1993). The scale is composed of eight items scored on 5-point Likert-type scales ranging from strong disagreement (1) to strong agreement (5). The eight items showed adequate evidence of unidimensionality, as well as adequate coefficient alpha and construct reliability estimates of internal consistency of 0.88. Four of the items (4,5,7&8) are reverse scaled thus appropriate adjustments are made to avoid data entry error.

There were 400 respondents in the final sample for this study. There were 11 unreturned and 2 unusable questionnaires, leaving a total of 387 respondents from whom data were obtained. To ensure data integrity, outliers are handled using Mahalanobis distance values. Similarly, the appropriate analysis is made to manage the negative impact of the missing values.

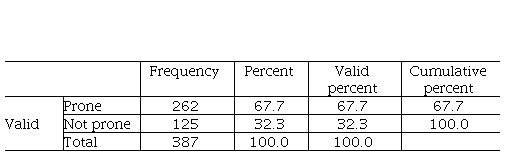

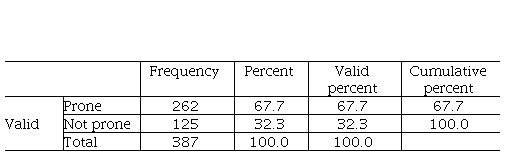

The respondents' proneness for nostalgic behavior is depicted in the following table. As it is discussed in the methodology part this study has used the nostalgia instrument by Holbrook (1993) which is a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from strong disagreement (1) to strong agreement (5). However, to meet the assumptions of a chi-square test, the original scale is changed into nominal data (prone/not prone). The conversion is made based on the principles of item parceling. As Bandalos (2002) established, the utilization of item parcels in the latent variable analysis is statistically acceptable. As can be seen in the table below 2/3 of the respondents are prone to nostalgia. Only a third are answered not prone.

Age is one of the characteristics used to understand consumers nostalgia proneness. The result portrayed that people aged between 45 and 64 are strongly prone to nostalgia than other age groups. A similar result is witnessed among those people between the age of 25 and 45. The youngest people have shown the least proneness towards nostalgia. The other characteristic is gender. Male is strongly nostalgic than women. More than 72% of males are nostalgic but only 61% of women are confirmed nostalgic.

In terms of marital status, the single group has exhibited higher proneness to nostalgia followed by the married people. Melody’s preference of respondents is also examined. Those people who are interested in both country and modern music are showed strong proneness towards nostalgia than those who prefer either of the two. From the watch and listen options, those who prefer video over audio music formats are strongly prone to nostalgia. The other very interesting characteristics examined is the occupation of music listeners. According to the result, temporarily unemployed people are highly prone to nostalgia followed by working part-timers. Permanently unemployed and the retired are showed the least degree of proneness. From the residence point of view, those who reside in rural areas are more prone than urban residents at 70% and 66% respectively. The last characteristic is religion. In this regard, it happens that Christians love their past more than their Muslim counterparts.

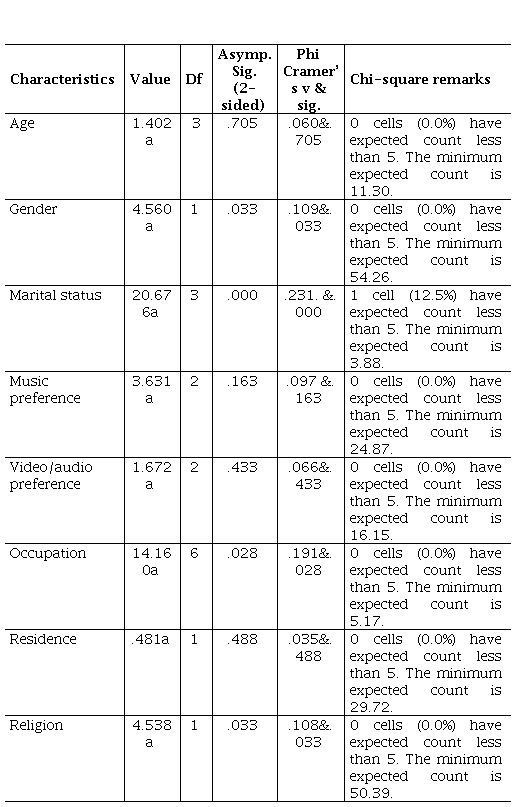

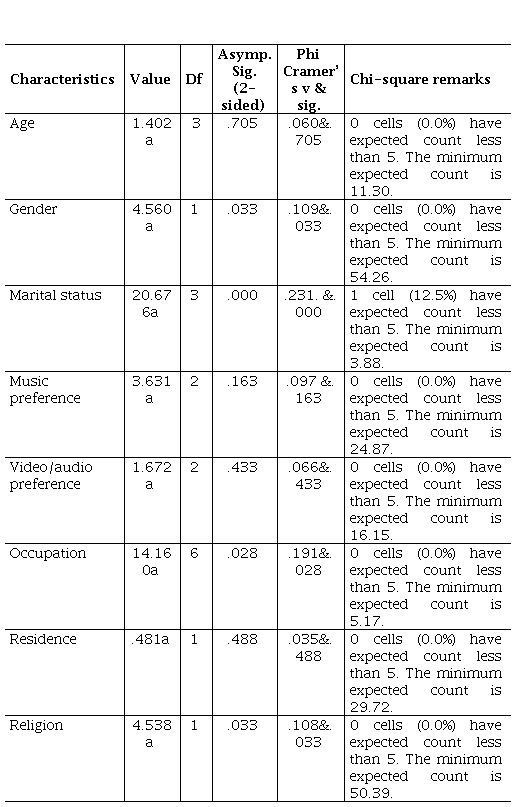

As recommended by various scholars’ nostalgia proneness usually understood better when it is examined for associations. This study has identified six predicting personal characteristics and two music-related factors to identify the degree of association between participants and their proneness to nostalgic adventure. In the study, nostalgia is tested for its dependence/independence to characteristics and factors using a chi-square test and Phi & Cramer’s value.

The statistical association between age and nostalgia proneness is predicted. However, as the result depicted at χ2(3) = 1.402, and p = .705, it is learned that there is no statistically significant evidence to show an association between age and nostalgia. Similarly, from the Phi and Cramer’s value, it can be concluded that the strength of the association between the variables is very weak. The other predicted association between gender and nostalgia is found to be statistically significant at χ (1) = 4.560, and p = .033 values. Likewise, Phi and Cramer’s values have shown a strong association. Similarly, a strong association is found between the marital status of people and their proneness to nostalgia at χ (3) = 20.676, and p < .001 values. Phi and Cramer’s values also shown a strong correlation between marital status and nostalgia proneness.

People's music preference and their inclination towards nostalgia are found to be statistically unsupported at χ (2) = 3.631, and p = .163. The Phi and Cramer’s correlation measures are also showing a very weak association between the two variables. No association is also detected between the audio and video preference of people and their nostalgia proneness at χ (2) = 1.672, and p = .433. From the Phi and Cramer’s correlation measures, it is also easy to learn the weak association. People’s occupation and their proneness to nostalgia are associated with χ (6) = 14.160, and p = .028. Additionally, the Phi and Cramer’s correlation measures are also showing a very strong association. At χ (1) = .481, and p = .488, it is found that there is no association between peoples’ permanent residence and nostalgia proneness. Furthermore, the Phi and Cramer’s correlation measures are also showing a weak association between the two variables.

Finally, our religion is found to be strongly associated with nostalgia proneness at χ (1) = 4.538, and p = .036. Correspondingly, the Phi and Cramer’s correlation measures are also showing a strong association between the two variables. Generally speaking, the results of the current study are very much in line with other studies in the past. For instance, a study by Friedman (2016) argued that brands are engaging through retro roots from fast food and breakfast cereals to gaming systems and everything in between. This result is another evidence for the existence of the positive relationships identified in this study. Similarly a study by Reed, Forehand, Puntoni and Warlop (2012) stated that certain music productions can signal and reinforce consumers’ self-identity, which results in one’s life experiences. Furthermore, as Barrett et al. (2010) described, nostalgia is associated with both joy and sadness, whereas non-nostalgic and nonautobiographical experiences were associated with irritation.

A result from Barrett et al. (2010) study confirms the rightness of most of the result of the current study particularly the issues nostalgia and music customers association to their past experience especially when they feel discomfort. The proposition by Marchegiani and Phau (2012) to marketing practitioners to be better informed when including nostalgic orientated music is also in line with the current result. This recommendation is mainly suggested because in most of the customers, a predisposition to personal nostalgia is found as a salient response; hence this fact in the customer's attitude provides continued support for the importance of music in advertising.

The average score for all nostalgia measurement items is close to four (before changing the data into nominal type), this is a strong indication for the nostalgic behavior of respondents. People at their mid-age 45- 65 are more prone to nostalgic feelings than under 45 and above 65. Male respondents are more susceptible to nostalgia than women. The single and married people are more exposed to the feeling of nostalgia, however, widowed appeared to be unsusceptible for nostalgia. Cultural and modern music fans are more prone to nostalgia than modern only and cultural only devotees. Those who want to experience music through video means are more exposed to nostalgia than other means. Temporarily unemployed, working part-timers and carer (who stay home to care for a family member) are strongly prone to nostalgic feelings. Rural residents are more susceptible to nostalgia than those who reside in urban areas. Finally, Christians have shown strong susceptibility than their Muslim counterparts.

Concerning the dependency test, nostalgia proneness has shown a strong association with gender, marital status, occupation, and religion. However, there is no statistical evidence to show the same association in age, music type preference, watching/listing preference, and permanent residence of people.

Nostalgia is prevalent throughout modern culture (Goulding, 2002); it creates a sense of authenticity, gives legitimacy to our way of life, and influences consumer behavior (Baker & Kennedy, 1994; Kasinitz & Hillyard, 1995). In applying nostalgia marketing decision-makers should take care of the sense of loss (negative nostalgia), because it may encourage unfavorable evaluations due to adverse associations and negative mood effects. As it is concluded in this study, nostalgia is an intriguing and prevalent circumstance and if taken seriously it can be like a new window of opportunity to make miracles in our marketing adventures. From a managerial perspective, the findings lend credence to and justification for the mangers in the music industry to offer products that strengthen consumers’ nostalgic responses. Therefore, now after this study, it’s easier than before to say that the opportunity for executing nostalgic marketing strategy is plenty.

There are some limitations associated with this study. First, the sample was taken largely from the largest city of in the country (Addis Ababa) and further research is needed to establish external validity across different parts of the country. As a professional researcher, I should admit that for such kind of pioneering and extensive research obtaining the equivalent level of resources was difficult, therefore the study may not be taken as the one and final piece of evidence for nostalgia proneness of music customers. Therefore, other scholars with sufficient time and money are expected to deeply investigate the issue. To understand all the dynamics at play concerning the effects of nostalgia on music consumer responses, it is important that further research is conducted by encompassing additional demographic and economic variables; expressly factors like ethnicity, income, and history. Finally, it is my hope that this descriptive study will inspire professional peers to examine nostalgia and how it affects consumer responses for diverse products.