Artículos

Care of the Self as a Practice of Resistance in Mental Health

El cuidado de sí como una práctica de resistencia en salud mental

Revista Filosofía UIS

Universidad Industrial de Santander, Colombia

ISSN: 1692-2484

ISSN-e: 2145-8529

Periodicity: Semestral

vol. 21, no. 1, 2022

Received: 03 March 2021

Accepted: 02 June 2021

Forma de citar (APA): Correa Blázquez, M., Fernández Ramírez, B. & Aranda Torres, C. (2022). Care of the Self as a Practice of Resistance in Mental Health. Revista Filosofía UIS, 21(1), https://doi.org/10.18273/revfil.v21n1-2022007

Abstract: When it comes to mental health, the medicalization of our everyday lives can diminish the autonomy that we hold over our health and care. Considering medicalization as an artefact through which power is exerted via biopolitics it is, however, possible to establish practices of resistance against it. Taking as starting point the testimonies of nine participants considered to be mentally ill, we reflect the relationship between subject and health-care system established through the care of the self as a practice of resistance when it comes to mental health.

Keywords: care of the self, autonomy, mental health, critical discourse analysis, life story interview.

Resumen: En lo que se refiere a la salud mental, la medicalización de nuestras vidas diarias puede reducir la autonomía que poseemos sobre nuestra salud y cuidado. Tomando la medicalización como un dispositivo a través del que el poder es ejecutado atravesando la biopolítica es posible, sin embargo, establecer prácticas de resistencia contra la misma. Teniendo como punto de referencia los testimonios de nueve participantes considerados como enfermos mentales, reflexionamos sobre la relación establecida entre el sujeto y el sistema sanitario a través del cuidado de sí como práctica de resistencia en lo referido a la salud mental.

Palabras clave: cuidado de sí, autonomía, salud mental, análisis crítico del discurso, entrevista de historia de vida.

1. Introduction: Body Terror Song

Michel Foucault presents a conceptualization of the notion of biopolitics in a course imparted in the Collége de France between 1978 and 1979, defining it as “the attempt, starting from the eighteenth century, to rationalize the problems posed to governmental practice by phenomena characteristic of a set of living beings forming a population: health, hygiene, birthrate, life expectancy, race...” (Foucault, 2008, p. 317). This trend comes with the dawn of the liberal mentality in politics and economics and the shift that it brings in its conception of the population as a civil entity surpassing the governmental authoritarian sphere. Presented as such, what biopolitics imply is a tight-knitted political relationship between the State, the population, and the subject[1] centered on the matters of life and health both in the individual and public sphere. With its precedents rooted in the anatomo-politics of the XVII century, preoccupied with the conservation, proliferation, and reproduction of biological processes in order to determine and guarantee the utility and productivity of the individual’s body —back when the first Hôpital Général is founded in 1656 in Paris— (Foucault, 1988), biopolitics as a by-product and complementary vessel of this ideals mark that which is desirable in the population in order for it to keep on living.

Chasing what has been deemed as desirable, biopolitics come with an exertion of power over the lives of the individuals and the population. This power is what Foucault christened as biopower and it is exerted by institutions in order to push the population towards goals related to its members’ lives and bodies through a myriad of strategies. A relatively well-known strategy can be found in censuses: Regarding Spain, the last massive official recollection of data by the government took place in the year 2017 through the National Spanish Health Survey, the last of which was conducted in the year 2020 by Henares, Ruiz-Pérez and Sordo. These strategies do not only provide information on the population and a means to control their data in regard to health, they also serve to highlight those deemed as undesirable or bad subjects, presumed as unable to follow the rules to which the population needs to abide to preserve its health. Those considered as mentally ill would be within this group, too irrational to know what is, allegedly, best for them and act accordingly and hence in need of help that comes in the form of therapy and, most importantly and prevalently, medication (Nadesan, 2008).

In the case of mental illness, the control over the organism that anatomo-politics propose and biopolitics extends to the population goes a step over the boundaries of life as an organic entity and seeps into matters of the self: “what happens when it is the self that is subjected to transformations in the hands of biomedical technology, when cognition, emotion, volition, mood and desire are open to intervention?” (Rose, 2012, p. 370). To briefly answer this line of questioning opened by Rose, the use of pharmacological treatments when it comes to mental illness is of particular note, since it experimented an increase alongside those classified as mood disorders since the XX century’s halfway point (Berardi, 2003) in a phenomenon consequential of what is considered as a byproduct and strategy of biopower: medicalization.

The medicalization of our everyday lives has been defined as the infiltration of health services in spheres of our lives that are not of medical entity and the transformation of mere circumstances of life such as aging or mourning into pathological situations (Kishore, 2002). When it comes to mental illness and its treatment, it opens the gates to two phenomena that run parallel to each other: 1) turning occurrences such as grieving and discomforts like unease into pathological entities hence blurring the line between health and illness and 2) creating dependence on medical treatment. Both phenomena come hand in hand with a mental health-care system under the pressure of the pharmaceutical industry (Frances, 2014; Ramos, 2018). With ambiguous diagnostic entities and pharmaceutical treatment as the most viable option offered, alongside the assumption that the mentally ill cannot properly take care of themselves, come uncertainty and the infiltration of medicine into facets such as the social, the professional and the familial and with it comes an encompassing denial of responsibility and autonomy over their health. As Illich (1975) puts it, “a system of health-care, based on doctors and other professionals, which has overflowed the tolerable limits [...] tends to expropriate the power of the individual to alleviate themselves and model their context” (p. 9).

We are, therefore, referring to a health-care system that determines what is and is not considered as mental illness with motivations that circle around the notion of a return to an idealized self-devoid of discomfort or frustrations (Rose, 2012; Berardi, 2003), with medicalization as a form of social control with a strong pharmacological standpoint (Conrad, 1992; Angell, 2004), in which those considered to be mentally ill are, beforehand, stripped of the capacity to choose which discomforts are more or less important in regards to their health and how to act upon them. It is a matter of concern since “in almost all this psychology, our psychology, what I find outrageous, to put it in four words, is its complicity with the system [own translation]” (Pavón-Cuellar, 2012, p. 202) referring to the system, according to this same author, as symbolic, cultural, ideological and of knowledge in Foucauldian terms beyond the economical and the political. It could even be argued that psychology, as a discipline finds itself hindered by its complicity, and has turned on itself, or has never been able to find its footing, and is unable to think, and express, itself in psychological terms; defining pathologies based on chemical or physical matters, or referring to a maladapted external cognitive structure (De Vos, 2017), with the consequences that this could have regarding how care could be provided. Having reached this point, it is worth asking if there are any alternatives. How can this situation be surpassed, if it can? Are those considered as mentally ill powerless when it comes to their mental health? Different authors tackle this issue in their own ways. Deleuze (1995), for instance, offers life itself, immanence, as an escape. Negri (2001) ponders on the political manifestations, aesthetic implications, and living options of the acceptance of one’s role as a monster within a society that marks them as irrational. Where Foucault is concerned, according to the author’s body of work, power relations contemplate their own practices of resistance. One of these practices is the care of the self (Duarte, 2012). For what concerns this particular text, we will focus on this former strategy.

Care of the self as defined by Foucault (2005) is a techné tou biou, a vital know how of life and for life, in which taking autonomous decisions based on the knowledge of oneself is key. This approach to care would be a practice of the subject over the subject, who transforms itself in favour of its own objectives. It is a critical practice of resistance to, amongst other aspects, medicalization as a control mechanism for those aware of both their historical standing, and the myriad of discourses surrounding health, health-care services, and the self (Hancock, 2018). Ultimately, this process would lead to a certain treatment of others that derives from the acquisition through that work of the self on the self of a noble ethos —taking both, the translation and how Foucault defines the concept, a way of being and acting by which one is perceived by and acts with others, and ultimately a particular form of freedom— which is exemplary (Foucault, 1999). In order to achieve this, two elements are of outmost importance: the restlessness of the self[2] (epimeleia heauteau) and the knowledge of the self (gnothi seauton). By being restless and curious about the self, one sets off to change and adapt following criteria based on one’s needs and goals; and by knowing the self-one does not acquire knowledge of essence but an understanding of that which objectifies us —categories such as male/female or sane/insane—and has being historically doing so through a complex, and ever-flowing, power dynamic. As Feito (2005) writes, “the attitude of care is a situation of sensitivity to reality, of taking conscience of its vulnerability, to allow it to question us and force us into action, as a way of humanity [own translation]” (p. 168), an attitude by which change is a constant and one never should never settle.

Being privy to the dynamics of knowledgeand power that are at the base of the objectification of the subject and having an awareness of the discourses surrounding that which defines us, we access games of truth, or the conditions of truth that the statements within discourses hold for us. Being aware of the power dynamics, of the knowledge-power articulation in and of itself and its operations, and the discursive entities in which they are immersed allows the individual to contemplate their own transformation with a better adjustment to experience: It offers access to discursive possibilities that might have been overseen until then, and to the consideration of problems linked to living, once they have been consolidated as subjects of knowledge that question the alternative of being defined by the medical gaze. This way is reached an “existential and Nietzschean turn towards an ethopoetical of life, the choice of the self as a critical attitude against the historical present would be defined as a self-forming activity, asceticism or a practice of the self [own translation]” (Macías, 2013, p. 91). As Foucault states, this would turn their lives into a work of art through the attempt of transforming themselves and constantly modifying their beings, both voluntarily and meditatively. In other words, the individual establishes a relationship with truth, and their self, that allows him for a critical attitude and, more importantly, implies an active part in the process that reclaims responsibility and autonomy:

Subjects study choices, relationships, possible decisions, life itself to determine for themselves means and ends. In this sense we are, then, talking about autonomy and the point to which subjects are free to choose what is more convenient for them [own translation] (Muñoz, 2009, p. 396)

When considering these choices, defining transformation is key. In the sense of the platonic epistrophé (being that the verb epistrophéin communicates the idea of physical movement back to where it came from, a turn, in the case of the individual a movement from the starting point a quo to an end point ad quem, a transformation), it is conceived as an act of reminiscence (anamnesis), by which instead of focusing on matters of this world versus the other one, what is suggested is to

[...] move from that which does not depend on us that which does. What is involved, rather, is liberation within this axis of immanence, a liberation from what we do not control so as finally to arrive at what we can control. (Foucault, 2005, p. 210)

In this sense, there is, once again, insistence over the matter of the individual’s sense of responsibility and autonomy (since it is them through their own means who can find that which they can be the master of), in order to form a relationship with itself that is full, accomplished, and self-sufficient to find practices of care and resistance that fit them. Considering this, we cannot provide any specific practice of resistance or care, being that they are bound to change through life and be tied to the subject. What they share is that the individual finds, in them, enough preparation to face life while keeping them open and adaptable.

At this point, there would not necessarily be a complete separation from the health-care system but a reflection based on understanding on whether or not that system would benefit the objectives marked by the individual for themselves and in which ways (Mol, 2008), considering that the know-how of the so called patient can and should be of value to complement medical expertise in a care relationship (Muñoz, 2009). In the case of those considered mentally ill, taking into account that by virtue of the division between the rational and the irrational they are already deemed incapable of managing their own health, we wish to inquire upon care of the self as a practice of resistance amongst them by reading the testimonies offered by nine of them as life story interviews —following the method proposed by Atkinson (1998) in which inquiry is left chronologically guided using a model but mostly open and the interview is subject to adjusting itself to the interview’s surfacing and developing themes— and looking for the practices of care that arise within them using critical discourse analysis (Van Dijk, 2001; Fairclough, 1995).

2. Methodology

In order to gather information on the participants’ strategies of care of the self, we conducted a life story interview with each of them. The life story interview strategy implemented is the one proposed by Atkinson (1998) and Pujadas (1992): The interviews followed a chronological order and were semi-structured; consisting of a fixed array of questions as the outline to follow from their childhood, to their future objectives, passing through their teens, but flexible in order to allow the pursuit of themes that might arise through the interviewing process without losing the chronological thread.

The participants (to whom we refer to using pseudonyms) Abel, Belle, Dan, Fred, Kim, Ken, Kaz, Vince and Viola, are all people who have had first-hand experience with mental illness (there are instances of them, the participants, using different terminology such as neuro-diversity, neuroatypicality or, even, insanity). Their diagnoses range from depression to psychosis, picked in such a way to access a more varied array of opinions and experiences, and only one of them, Vince, was ever institutionalized (in their case, during childhood). They are all young adults, all of them aged between 20 and 28 years old, and they are active on social media. Seven of them answered a call to action posted on social media directed to people considered mentally ill who wanted to share their experiences, the other two asked to contact us when they were made aware of the project by word-of-mouth. All the participants except for one, Kim, who is North American, are Spanish and they all are part of an encompassing white Western culture. Regarding gender, they were five men, three women, and one non-binary person (even though they were the only one who manifested to be non-binary, at least two more of them were exploring different possibilities when it came to gender). To protect their anonymity, we will use neutral pronouns with all participants.

During the interviews, conducted both face-to-face when the circumstances allowed and through Discord call service otherwise, they shared with us their lives and experiences as people considered to be mentally ill. The primary quality check regarding validity followed a standard of internal consistency, as advised by Atkinson (2002), meaning that one part of the narrative offered by the participant should not contradict what they say in any other given part. Following this author’s instructions, when faced with such contradictions, we considered that “there are inconsistencies in life, and people may react to things one way at one time and different ways at others, but their stories of what happened and what they did should be consistent within themselves” (p. 134)

The interviews were complemented with an analysis of the participants’ social media presence: We followed them on Twitter, which all of them used, and selected those of their tweets and retweets that included themes related to mental illness. We performed a critical discourse analysis in Foucauldian form (Banister, et. al, 2004) both on the interviews and the tweets, finding emergent crystallized narratives and analysing them in terms of discourse, power structures, and participant experience and role (Van Dijk, 2001; Fairclough, 1995; Marwick, 2013).

What surfaces is a critical discussion based on the practices of care emergent throughout the interviews and observed in our following interactions with them coupled with fragments[3] from said interviews and social media posts[4] to showcase that which was directly said by them when relevant.

| Participant | Age | Gender | Working status |

| Abel | 27 | Man | Manager of a music academy |

| Belle | 20 | Woman | Art student |

| Dan | 28 | Man | Clinical psychologist |

| Fred | 25 | Man | Medicine student |

| Kaz | 20 | Man | Waiter |

| Ken | 23 | Man | Medicine student |

| Kim | 24 | Non-binary | Literature graduate |

| Vince | 26 | Man | Socio-sanitary attention student |

| Viola | 26 | Woman | Pedagogue working in mental health |

Participant data

Note: own elaboration3. Practices of resistance

What follows is an exposition of different ways in which participants took care into their own hands. It is worth reiterating that when referring to Foucault’s care of the self this does not only imply direct contact with and transit through the health-care system, but a know-how and an attitude of life that permeates other aspects of living and one’s relationship with others.

3.1 The health-care system: Reclaiming responsibility in a medicalized context

When it comes to the health-care system in and of itself, participants did not advocate for complete emancipation. The reasoning behind this varies but, ultimately, is tied to the perception of the nature of mental illness in the health-care system as a malady of the self in contrast to a malady of the organism[5]. As such, it is paired with its own set of complications when it comes to recognizing that there could be something off to begin with, and eventually seeking treatment: Participants manifest that there is an initial barrier that they needed to overcome, related to views on mental illness and its professionals held by their families and peers. Recognizing that they need help in any way comes with a complicated set of feelings and views coupled with jumbled and confusing discourses on mental health passed down by family and peers and through popular culture.

Well, I’ve always strongly rejected psychologists and psychiatrists because my father always told me that it was all blarney, that it was all made up, that they were con-artists, that it’s a matter of trying, that it heals by itself. So, I’ve always thought that this was because I’ve been taught that they were useless. That was something for weak people or lazy people or miscreants. After that with time my perspective changed, I’ve met people who’ve had a rough time that they’ve helped and I’ve seen that my father was wrong. Nonetheless I haven’t gone (to therapy) because there was still some shame left in me, as if going to the psychologist or the psychiatrist was recognizing a weakness or making a problem real that is like there but like in the back of my head.

Abel (27)

I saw her sleep a lot and I saw that she was unwell and I saw that she took pills and that she went to the psychologist and my mother is a person who has always accepted mental health too and has had everything very well defined and when my mother has had X problem she has gone to a professional and has gone to a psychologist or a psychiatrist. In my house mental health is like a very open subject and in fact when I was diagnosed well I was diagnosed with depression and an anxiety disorder I was always very clear on what I had to do, right? That initial barrier that everyone has regarding mental health isn’t in my family.

Viola (26)

As Abel (27) and Viola (26) refer to, both in different ways related to their own experiences and discourses available to them surrounding mental health and its professionals, seeking help when it comes to worries related to mental health is not an easy process and it passes through, first and foremost, recognizing that something is amiss with the implications that this may have in the individual’s perception of the self. For instance, it could be stated that for those who had to go through the, adequately named by Viola (26), initial barrier the process implies a sense of alienation that runs with how irrationality is historically perceived and defined: As a malady of the self, it implies shame, weakness, failure, and helplessness. It is a hurdle that they have to surpass or navigate in certain ways, be it by being privy to certain discourses regarding mental health and its professionals that are more open to treatment, as Viola (26) was, or by dealing with those associations and overcoming them, as Abel (27) talks about being in the process of doing. To reach this point, participants had to, previously, work on identifying a problem and trying to work on it themselves.

When participants recognize that there is something that they have to work on or improve upon, they start gathering knowledge both on how it operates within their own lives and sense of self, and on how the issue has been already tackled by others. At this point, the problem that participants faced was that the strategies presented to them did not work and with each failure, their frustration grew. They knew what was not working, they knew what they wanted to improve upon, they had notions on how to fix it, but it was not working for them. Eventually, they hit an impasse that forced a decision to reach out either to family and peers or the health-care system directly:

The simplest emotional work I’ve already done myself. My main problem is that even if I know that something happens because this or that...I can’t manage to stop it. In fact, the phrase I repeat the most always with my psychologist to a point that just by looking at me she started saying it back because she knew what I was thinking is: Yeah, I know, but I can’t help feeling like this. So, I think that what I have to work on the most is strategies to...shit, just what I was saying, having made that emotional work of knowing why I feel a certain way, rationalizing it myself, there’s no objective reason why I should feel that way, so I wanna know even just a hint of what to do with all that, how to take the next step to stop feeling that way.

Vince (26)

Because I was already, during high school, having a lot of depressive episodes, I didn’t want to go to school, I didn’t want to see people, and I was sick of not being capable of having friends. I don’t have a very clear recollection of it, but fundamentally those were the reasons. And between all that anxiety, all that depression, and all that discomfort one day I suggested the possibility of...what if I go to a psychologist and talk about this? Or we try to determine if there’s something going on with me. And my mother...she thought it was a good idea and decided to take me there

Dan (28)

I noticed that my problems were becoming bigger. I stayed full days in bed without practically doing out because I didn’t have the vital energy, to put it that way. So: I did nothing, I had no interest for anything and man, I knew that it was a problem but even then, I kept saying that it was just a rough patch, it would be over and so on and so forth. But well, my current partner was very insistent on me going (to therapy) but I kept pushing away and saying no. And well evidently, when they suicide, attempt happened, I realized that, objectively, that wasn’t okay, and I was really unwell as I had been told some years prior

Ken (23)

Hence, as Vince (26), Dan (28), and Ken (23) exemplify, seeking guidance, to the participants, was not as much a matter of trying to understand what was happening to them but acquiring the tools to solve problems that bothered them specifically and that they could not face on their own, even when they had been able to understand why those problems were happening, or, as Dan (28) says, a matter of seeking a chance to talk about something that’s happening to them.

Either directed by those closest to them, like Ken (23), or having approached them themselves, like Dan (28), once having taken the decision to turn to the health-care system and mental health professionals, participants found systems, tricks, and strategies that helped them navigate that particular situationin ways that were effective for their own preferences and goals.

The other day I went to see a new psychiatrist and she made such a mess during the session. She crossed every single red line that you can cross during an appointment[...]. And then, with the matter of the abuse, she started yelling about how shocking it was, and whatever, how can someone touch a child. And I had to stop her and tell her, no no, listen, nobody touched me, my abuse wasn’t like that, it was different[...]. And I laughed and she said this is not a joke and I kept on laughing thinking I can’t believe this. Is this really happening to me? And I came out of that appointment telling my friends listen, I don’t know if I went to see her or if she came to therapy with me. I don’t know. And I’m not going back.

Viola (26)

Viola (26) is the participant with the most poignant retelling of a bad experience during an appointment, including the things she did during it, despite not being the only one who has had such an experience with a mental health professional. As her testimony shows, she had to handle the situation on her own, interjecting and even correcting the psychiatrist, bewildered by her attitude and words as she was. Ultimately, she had, as we stated prior to her testimony, to take a decision and stick to it. One could argue that this is the expected outcome when an individual faces a situation of any nature, but as we prefaced this text with biopolitics, biopower and medicalization it could be considered in those terms as follows: In a medicalized society it is already difficult to make autonomous decisions when it comes to matters of life such as whether or not it is healthier to take a leisurely walk or stay at home reading according to the latest trends in public mental hygiene, when it comes to facing a system that classifies, prescribes, and first of all considers one as incapable of exerting care this is the first instance of reclamation of responsibility that they show others. Note that it is not the first instance overall, since they start working on themselves and trying to find other ways before they resort to professional help.

As Mol (2008) argues, complete emancipation from the health-care system and leaving the patient (her term) to their own devices is not necessarily concurrent with a more responsible and autonomous way of care since it does not imply in and of itself that the person is taking any choices that matter to them. More importantly, it closes the door to a set of discourses that are valuable not because they are legitimated by the institutions at hand, but because by knowing them those considered as mentally ill have access to more possibilities of choice. Hence the benefits of a patient-professional relationship that allows for dialogue and working hand in hand.

In the case of the participants, the experiences they share with mental health professionals are marked by the potency of their own voices in the dialogue. They have goals, they know what they want from treatment, and they recognize themselves as active agents of care. Do they always do what they are supposed to do, or what is supposed to be right? No, but they do assess how their choices affect them and how they are conductive to their own goals regarding their health and lives.

After that this psychologist took a maternity leave and was eventually fired, another one came and the workshops’ dynamics were totally different. I’m not saying they were bad, but they weren’t giving me anything…useful? Let’s say that they weren’t giving me a function…they weren’t giving me an opportunity to function in a determined way that was positive for me. […] From that moment onwards, I haven’t gone to the association anymore.

Dan (28)

If you had asked me last year with another psychiatrist, I would have evaluated it negatively, because of what I told you. Because when you don’t care about what the patients feels or about understanding their illness but you simply treat them with medicines there’s a failure on you and a failure on the patient. So, with the new psychiatrist he doesn’t only treat me pharmacologically, but he contemplates understanding my illness, understanding me as a person and seeing me as a person not as a diagnostic label.

Fred (25)

As Fred (25) presents, there is value in seeing someone beyond their diagnostic label and recognizing their humanity. This is key when it comes to a therapeutic relationship that can be fruitful for those who are applying the care of the self since it allows for a dynamic give and take instead of a paternalistic, thou-shall/shan’t. It would mark the difference between chastising Dan (28) for leaving treatment, something that a mentally ill person should not do since they need the help that they cannot provide for themselves, and being mere observers of Dan (28) as someone who decided that, upon finding that his objectives were no longer being realized, took it upon themselves to make a choice regarding their own health.

3.2 For the self and on the self: The act of being

When inquiring upon what they liked to do for their own comfort, participants often referred to simple things that they could do by themselves such as taking walks, listening to music, or reading. Being that they all had different preferences, where a commonality was found was in the basic pleasure of being able to decide what to do, when to do it, and doing it without a particular objective beyond the act in and of itself. It was a matter of what valuable acts of care they could incorporate to their routines.

As it turns out, when it came to working on their goals when maintaining their mental health, they found that they struggled with accepting that sometimes things can be done because they are things that we like doing. Methods on how to achieve this changed based on their preferences, but ultimately, they lead to finding comfort in being without having to be doing anything of much consequence.

I had a time during treatment and all that in which I thought that doing things that didn’t have a repercussion after on, say, I don’t know professionally or I don’t know on your health…not on your health but maybe on your physical appearance I thought that maybe I don’t know why would I be reading a book or novel if I could be reading a book related to my degree that is going to help me know things afterwards. And with time I’ve been realizing that maybe you can read a novel because you like it and because you enjoy that moment in which you’re reading the novel and, in the end, I think that that’s health. […] To me breaking that belief that everything I did had to have a let’s say professional undertone or be something objectively useful, a utility would be the thing, breaking that barrier freed me a lot.

Ken (22)

The idea of those considered to be mentally ill as a burden to a system that prioritizes production was already explored by Foucault (1988) when investigating the genealogy of madness, particularly where the conception of institutionalization is concerned. Considering mental illness as a disruption of the self in the terms that Rose (2012) and Berardi (2003) present, it aligns with the current trend consisting of taking happiness and complete absence of discomfort as ideals, leading to the pathologization of even mild inconveniences and minor discomforts that, nonetheless, function as obstacles for productivity and, more importantly, achieving the hygienic goals set. Reaching the conclusion that they do not need to be productive in order to have a realized self, as Ken (22) says breaking that barrier, puts the conception of their selves as inherently malfunctioning in question and allows them options through which to transit and explore those selves creatively.

Usually, it's just me drawing someone looking angry when I'm upset about something or someone looking very happy when I'm excited but don't want to move around. Cause like growing up anxious and everything I have a tendency to not like really express what I'm feeling and it ends up in a lot of energy that it's not getting out.

Kim (24)

I really like doing relaxing things. I love washing my hands because I like feeling the cold and that my hands are clean, my face too. I’ve changed my hairstyle a lot, I’ve cut it. Changing my image has helped me. Sometimes I meditate, I simply lie down and feel…I don’t know the sun for instance in summer when the breeze hits just right or I listen to chill music. I’m doing things at my own pace.

Belle (20)

These practices are, ultimately, auto to auto: For the self and on the self. Kim’s (24) drawings are reflective of their mood, Belle’s (20) meditations and cleanliness are for nothing but their own pleasure. Their implications beyond that are of little to no consequence (we can mention, for example, that when reading for pleasure one can also acquire useful knowledge for work yet why would we, in which capacity do we need to justify this act when we are seeking to defend it as worthy in and of itself). As an ethopoetical of life, as Macías (2013) puts it, they imply the choice of partaking in that which they want to do over what the historical moment keeps asking of them, not by chance but by reflecting upon what they like and want to do and what helps them reach their own goals when it comes to the act of being. When faced with the demand produce, the answer is not exactly no, but turning around to do something else entirely involving their own transformation.

As such, it is of interest as a practice of resistance in how it does not necessarily object nor deny any particular discourse or institution directly. We have mentioned how it functions as a way to turn away from the idea of the idealized, productive and happy, self but in and of itself it is not actively making any statements. It is not a ferocious fight to upend an unfair and oppressive system (it would defy its purpose to be so, first and foremost, and besides some even like being organized, using that as their method), but a way in which that system can be navigated and tricked regardless. As such, we could say that these acts are reflective of an existing techné tou biou, a vital know-how that allows them a space in which to be with themselves.

And also…changing saying I’ve done nothing to something else. If I’ve watched a show well, I’ve watched a show. I’ve relaxed. I’ve done something.

Viola (26)

It is like magic, blink and you miss it, a trick of the light: As Viola (26) states, change one thing for the other; almost a play on words. After all, the historical present holds within itself plenty of tools to misuse.

3.3 Becoming exemplary: social media and communities online

We kept in contact with the participants through social media during and after the investigation. What we found through this and through the interviews was that they were part of an active, vocal, and restless community of people considered to be mentally ill online who communicate using social media applications.

This is where care of the self takes its last step towards a noble éthos, from a practice of the self on the self, auto to auto, to a practice that extends to and is shared with others (Foucault, 2005). Participants found themselves reading on mental health mainly through two social media applications, Twitter and Tumblr, as well as sharing their own knowledge and experiences with others using them.

Interviewer: And you have been telling me that you're sometimes anxious, that you had a panic attack. This kind of vocabulary, is this something that you've searched, that you've heard from people or that...?

Kim (24): I'd say heard from other people because it's more something I've picked up over time like on Tumblr and twitter.

Later on, and this is really funny to me, I learned on Tumblr that when you have a panic attack you can think of four things that you can listen to, three things that you can whatever. I learned that from Tumblr which I find so funny, learning something like that on Tumblr.

Viola (26)

As Kim (24) and Viola (26) comment, they found useful information on social media regarding their worries. Participants more connected to activist circles or who were members or founders of organizations themselves use these platforms to share organizational messages and what could be considered as public service announcements, while others use them as journals in which to share their own experiences, tips, and tricks. Some even use them for various purposes at once, having different accounts dedicated to activism, journaling, jokes or socializing. Ultimately; what these platforms offer is a level of self-expression and flexibility that most lack, giving them the tools to share their thoughts and experiences.

Being that these platforms are free to use and global, they are populated by a myriad of people and these communities on social media are not homogenous and do not follow a traditional organizational structure. They consist of a cacophony of voices sharing information on what was useful for them, on how they feel about certain things, how they experience their discomforts, and practical information on how to approach the health-care system. The platforms’ structure allows for discussion that is global and the posts rarely ever are static, showing responses and debates about the themes proposed. Albeit some discourses of mental health show more popularity than others (amongst participants, the neuroatypical movement of the 90’s[6] and a new wave born from activism focused on seeking help in whichever form were particularly popular), it would not be accurate to say than any one of them rules over the rest: Any given post will have its followers and detractors.

Where participants are concerned, social media is a tool through which to open discussion and share their ideas. Once they have learned ways through which to traverse their historical present and the obstacles that come with it, they become a part of their lives and the way in which they carry themselves through it: They are habit, what they do and how they do it, they become éthos and it permeates every aspect of their journey. All participants shared this desire to communicate, to be open about their mental health and their thoughts about it. This does not only help them be present, as a voice in the dialogue on mental health, but it keeps them exploring and discovering viewpoints and techniques they might not have known before. Their willingness to be active in a community that shares information is testament to them not settling and keeping up with their care while keeping an eye on their own community.

Figure 1

Twitter user on recovery

Figure 2

Twitter user on feeling heard

In the process, they encounter contradicting voices and information. As shown in the screenshots, there is a critical attitude and self-awareness. The use of terminology differs as evidenced by the neurotypical (which refers to a person who is not considered as mentally ill) being written in quotations in the second screenshot. Within the replies to the first tweet there could be found a debate on the use of recovery, and the second tweet was a reply to a tweet on the representation of mental illness in popular culture. This dialogue allows access to new discursive horizons, which serves as the fuel to keep on working on their own care.

By the mere nature of it as a pastiche of voices, sometimes even images, what we can witness when looking for tags such as mental health, mental illness, neuroatypical, or neurodivergent is as varied as these terms themselves. The terminology found in the participants’ tweets and retweets ranges from the most medical and sanitized to the most taboo and outrageous. And what is most interesting and refreshing regarding our subject matter, it does not necessarily concern itself with using any terminology as it was intended to, nor with been even remotely comprehensible by those unfamiliar with the scene.

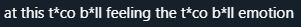

Figure 3

Twitter user on their feelings

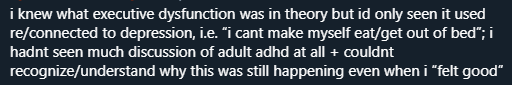

Figure 4

Twitter user on their experience with ADHD as an adult

The first screenshot is almost esoteric in nature, obscure enough to boggle the mind. Yet it evokes a very specific emotion on the reader who is privy to its meaning and knows what the alleged taco bell emotion entails. We, as outsiders, do not know and we should not concern ourselves with it: It is their feeling to define and understand, and ours to puzzle upon and wonder if we ever feel it too. Regarding the second screenshot, the twitter user who wrote the post did it so others could be familiar with the experience of ADHD on adults since they could not find information that was useful to them. Regardless of what we think about ADHD as a diagnostic label, the user uses it as a means to communicate those symptoms traditionally related to a certain illness might not be connected to it at all, which confused them when feeling like they should not be experiencing them. It is an interesting post, informative, to the point, and useful for those who might be going through the same process.

As a way to maintain a relationship, of which the core is health, with the self and with others the building of a chaotic yet vocal community offers more than just resources. If we follow Negri’s (2001) reflections on the monster we would have encountered one that is most preoccupied with the experience of its own monstrosity above all pretensions of ruling or positioning itself in contrast to anything else. There might be voices within the chamber claiming for revolution or establishing comparisons, but they are only some squares in a patchwork quilt. All in all, what this represents is a collective that is refusing to be pegged down by the medicalized society that deems it as an infeasible self, resisting biopower, and hence medicalization, not by naming them but by discreetly turning their backs to them and choosing to play and grow by its own means: It is in that lack of cohesion where it thrives.

4. Conclusion. Normalization Blues

Those considered as mentally ill are charged with a responsibility that comes with a historical present in which governmental practices have the perpetuation of life as a main concern (Foucault, 2007): As undesirables, “bad subjects” too irrational to even know how to properly take care of themselves, they need to be helped to become “good subjects” who will be able to keep on living as envisioned (Nadesan, 2008). Ultimately an exertion of power through biopower and expressed in medicalization, it is quite the heavy burden considering that they are deemed incapable of knowing what is best for them to begin with, and puts the health-care system and its agents in a particular position over them that is almost paternalistic in nature. Stripped of responsibility and autonomy by those who are supposed to take care of it (Illich, 1975), when it comes to mental health care of the self becomes of particular interest since their self is deemed as faulty (Rose, 2012).

The Idealized Self as a goal is a heavy burden to carry. It is happy, satisfied, able to be productive without feeling any anxieties, neurologically unmarred, a child of a romanticised idea of Prozac and the myriad of medical treatments that accompanied it as saviours of the mentally ill (Angell, 2004; Berardi, 2003; De Vos, 2017). Taking it as a product of psychology as a discipline that is complicit with a system that pushes for the individual to adapt to the status quo, through this normalization they become instruments and are exploited, transformed into the gears that serve to move that same system forward (Pavón-Cuellar, 2012). When questioning whether or not we might have a mental health problem we come face to face with this idealized self and by virtue of its existence within the public conscience it places those who have not reached the goal as something else: A failure of its ideals, an aborted self and, as previously stated, a bad subject that is weak, useless, shameful, impossible to help itself. Interestingly, as participant’s testimony shows, it also reserves a place for mental health care professionals within the discourses that it produces as charlatans and scammers, presumably since it assumes that they provide therapy instead of medical treatment, and the fractured self cannot be rebuilt. It can be mended by intervening on its imbalances, one by one, with the pill specifically designed to fix them.

Yet participants were not helpless, nor were they a collective of shipwrecked selves blindly searching for their next prescription. Through the care of the self, they found ways to reach their own goals that defied the notion of the broken self by prioritizing those objectives overreaching the status of the idealized self, while not necessarily emancipating themselves from the health-care system.

First of all, they pondered on their worries alone. The need to understand those worries was the driving force that took them to reflections on why that particular worry was problematic to begin with, to whom, how to fix it, if there were more people going through it, what was mental illness, what being sick enough entailed, and, all in all, a journey through knowledge kick-started by a desire for change that culminates with a hand reaching out. Their relationship with the health-care system, in that way, is one that starts with a set of expectations that is already high: They have already started working on themselves, they know what they want but they cannot find the way to achieve it alone. In a way, what they need the health-care system for is to establish the first meaningful conversation about mental health, open themselves up to new discourses and options that they can accept, refuse or transform. It is the pole that can be used to jump over an obstacle and keep running, and in its nature as a tool it is useful only as far as it fits its purpose. Once it stops being of use, it can be discarded. Conceptualized in this way, the participants’ approach to mental health professionals and what they had to offer was born from the need to have a dynamic dialogue on mental health that touched on their own goals and needs. In this sense, it aligns with how Mol (2008) and Feito (2005) define what would be a good relationship between medical professionals and patients, one of sharing and patient responsibility, as the testimonies show that they are making choices. These are not casual, but based on critical thinking regarding the knowledge they hold and what they have already decided that they want from the health-care system.

This relationship is one of the most interesting aspects of the care of the self as a practice of resistance since at first glance it does not appear to be meaningfully critical or aware of medicalization and what it entails. It could be even argued that they were falling prey to it, letting it define them by resorting to its systems and falling down its trappings. What marks the difference and makes their approach special is that their objectives are defined by worries that affect them directly and not by a worry to be normal, good, subjects that can finally serve their purpose in society and be model citizens. They show that they can be critical of the system that, essentially, problematizes them and needs to change and be better by them (participants were, after all, active in mental health advocacy and counter cultural movements, one of them even leading their own organization), but while it takes the steps to do so they make use of it. It would be a cruelty to themselves not to at least demand as much: Their awareness should not negate the demand for care, be it through a critical relationship with the health-care system or by just being with themselves.

This was another peculiarity that seems of note. The realization that they do not need to be productive, that they can do things for the sake of doing them and that in and of itself is a healthy practice (without meaning to be) is of particular interest to us. How many of us have realized that we do not need to be productive and useful all the time? As a practice of resistance, which Foucault in other works calls practice of freedom, it is as liberating from a system that demands productivity from the good subject as any practice can be. It evokes Deleuze’s (1995) writing on life and immanence: their actions do not have to transcend; they are preferably immanent and stay in the present as actuality. Living for the sake of living, doing things with oneself just for the pleasure of it, presents itself as a radical way to unintentionally oppose a system that demands that we live and that we are as happy as can be to be functional for it (Berardi, 2003).

While of note, it is not the only instance in which participants show a turn from what they are expected to do. After all, power contemplates its own opposition and as such it does offer options (Foucault, 2019). When it comes to mental health, the participants did not manifest any approaches to institutionally organized efforts towards the alleged benefit of the mentally ill, they turned to social media instead. At this point, in the journey through care they have already established their own path through it and are still traversing it and, in that process, sharing almost comes naturally. After all, it is already part of their éthos as Foucault (1999) would define it; it is a part of how they live and behave and it transpires to their interactions with others. Participants did not wish to be part of the normalized society, the fabled neurotypical mass, they did not necessarily call themselves mentally ill but they recognized themselves as people with a history that separated them from that and valued the knowledge that it gave them. It is, partly, an acceptance of their monstrosity (in that they do not fit the mould and are something else) yet it does not follow Negri’s (2001) reflections on monstrosity as an upending force of the status quo.

Participants showed a tendency to the nomadic when it came to this recognition of them as something else. Alongside the care of the self comes the idea that this work of the self over the self, auto to auto, is a process that has to be maintained through life. As such, with the aperture of the discursive horizon that came with sharing experiences online came the possibility of constant work on the self in terms that mattered to them. If they are not what we are all supposed to be, then what are the possibilities and how can they approach them become matters of importance and debate, and their community thrives on dialogue and the ever-changing natures of both its actors and its worries. The discursive twists and turns make matters almost impossible to pin down, to make psychologically (and scientifically) useful, since “the effect of these shifting mutations and simultaneous existence of explanations, with no one of them privileged is that traditional psychology loses its ability to speak as myth” (Correa de Jesús, 1999, p. 78). Consequentially, in this case, it is not as much, or at least not only, a matter of how the individual negotiates their own mental health and shares such a process online, but of discourse ecology, community, and redefinition. As Parker (2002) writes in Critical Discursive Psychology regarding this type of community online: “Here conventional psychology will not work. Interaction does not follow the rules identified by social psychologists, biographies do not follow the narratives traced by developmental psychologists, and memory is not accessed in the ways cognitive psychologists would expect” (p. 15). It is, therefore, a space in which rules are rarely ever followed, and one of, as Parker concisely puts it, dispersed subjectivity that fosters, both, dialogue and change.

Ultimately, what makes the care of the self as a practice of resistance so interesting when it comes to mental health is not only that it outwardly challenges the conception of the mentally ill self as fractured, but that it offers both a sense of autonomy and responsibility that rests on objectives that are critically self-defined and evolve with the individual away from a need to assimilate to a normalized, idealized, self while having a therapeutic function outside the boundaries of formal intervention.

References

Angell, M. (2004). Excess in the Pharmaceutical Industry. CMAJ, 171(12), 1451-1453. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1041594

Atkinson, R. (1998). The Life Story Interview. Sage Publications.

Atkinson, R. (2002). The Life Story Interview. In J. F. Gubrium and J. A. Holstein (Eds.). Handbook of Interview Research. Context and Method (pp. 121-140). Sage Publications.

Banister, P., Burman E., Parker, I., Taylor, M. & Tindall, C. (2004). Métodos cualitativos en Psicología: Una guía para la investigación. La Noche Editores.

Berardi, F. (2003). La fábrica de la infelicidad: Nuevas formas de trabajo y movimiento global. Traficantes de Sueños.

Conrad, P. (1992). Medicalization and Social Control. Annual Review of Sociology, 18, 209-232. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.001233

Correa de Jesús, N. (1999). Genealogies of the Self in Virtual-Geographical Reality. In A. Gordo-López & I. Parker (Eds.). Cyberpsychology (pp. 77-91). Palgrave McMillan.

Deleuze, G. (1995). La inmanencia: una vida… In G. Giorgi & F. Rodríguez (Comps.). Ensayos sobre biopolítica. Excesos de vida (pp. 35-40). Paidós.

De Vos, J. (2017). No hay futuro sin crítica de la psicología: una interrogación del marxismo al psicoanálisis. Teoría y Crítica de la Psicología, 9, 16-35. https://www.teocripsi.com/ojs/index.php/TCP/article/view/207

Duarte, L. E. (2012). La resistencia en Foucault. Algunas relaciones en torno al 15-M. Revista Filosofía UIS, 11(2), 97-122. https://revistas.uis.edu.co/index.php/revistafilosofiauis/article/view/3366

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Longman Publishing.

Feito, L. (2005). Los cuidados en la ética del siglo XXI. Enfermería clínica, 15(3), 167-174.

Foucault, M. (1988). Madness and Civilization. Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (1999). La ética del cuidado de sí como práctica de libertad. In A, Gabilondo (Trans.). Estética, ética y hermenéutica. Obras esenciales, Volumen III (pp. 393-416). Paidós.

Foucault, M. (2005). The hermeneutics of the subject. Palgrave Macmillan.

Foucault, M. (2007). El nacimiento de la biopolítica. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Foucault, M. (2008). The Birth of Biopolitics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Foucault, M. (2019). Un diálogo sobre el poder y otras conversaciones. Alianza Editorial.

Frances, A. (2014). ¿Somos todos enfermos mentales? Manifiesto contra los abusos de la Psiquiatría. Ariel.

Hancock, B. H. (2018). Michel Foucault and the problematic of power: Theorizing DTCA and medicalized subjectivity. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 43(4), 439-468. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/jhy010

Henares, J., Ruiz-Pérez, I. & Sordo, L. (2020). Salud mental en España y diferencias por sexo y por comunidades autónomas. Gaceta Sanitaria, 34(2), 114-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2019.03.002

Illich, I. (1975). Némesis médica: la expropiación de la salud. Barral Editores.

Kishore, J. (2002). A dictionary of public health. Century Publications.

Macías, J. M. (2013). ¿Qué es una formación socrática? Paideia, parresía y buen uso de la razón. Revista Filosofía UIS, 12(1), 85-97. https://revistas.uis.edu.co/index.php/revistafilosofiauis/article/view/3514

Marwick, A. (2013). Ethnographic and qualitative research on twitter. In K. Weller, A. Bruns, J. Burgess, M. Mahrt & C. Puschmann (Eds.). Twitter and Society (pp. 109-122). Peter Lang.

Mol, A. (2008). Thelogic of Care: Health and the Problem of Patient Choice. Routledge.

Muñoz, N. E. (2009). Reflexiones sobre el cuidado de sí como categoría de análisis en salud. Salud Colectiva, 5(3), 391-401. https://doi.org/10.18294/sc.2009.242

Nadesan, M. (2008). Governmentality, Biopower, and Everyday Life. Routledge.

Negri, A. (2001). El monstruo político. Vida desnuda y potencia. In G. Giorgi & F. Rodríguez (Comps.). Ensayos sobre biopolítica. Excesos de vida (pp. 93-140). Paidós.

Parker, I. (2002). Critical Discursive Psychology. Palgrave McMillan.

Pavón-Cuéllar, D. (2012). Nuestra psicología y su indignante complicidad con el sistema: doce motivos de indignación. Teoría y crítica de la psicología, (2), 202-209. http://www.teocripsi.com/ojs/index.php/TCP/article/view/97

Pujadas, J. J. (1992). El método biográfico: el uso de historias de vida en ciencias sociales. Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Ramos, J. (2018). Ética y salud mental. Herder.

Rose, N. (2012). Políticas de la vida: Biomedicina, poder y subjetividad en el siglo XXI. UNIPE Editorial Universitaria.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2001). Critical Discourse Analysis. In D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen, & H. E. Hamilton (Eds.). The Handbook of Discourse Analysis (pp. 352-371). Blackwell Publishers.

Notes

Author notes

Additional information

Forma de citar (APA): Correa Blázquez, M., Fernández Ramírez, B. & Aranda Torres, C. (2022). Care of the Self as

a Practice of Resistance in Mental Health. Revista Filosofía UIS, 21(1), https://doi.org/10.18273/revfil.v21n1-2022007