Abstract:

Purpose Discussions about sustainability in the organizational context present a blind spot. It appears when we ask if a company recognized as sustainable, keep what it means compatible with corporate sustainability premises and its values on the strategic decision process. In this context, the purpose of this paper is, on the light of sensemaking and the decision-making theory, to reflect on possible divergences between meanings attributed to sustainability, available on official documents, and the meanings identified in current actions and narratives related to sustainability goals in the researched organization. Design/methodology/approach The research adopted a qualitative approach, characterized as descriptive, using as methods narrative analysis and documentary research, that were carried out from sensemaking theory. Findings It was identified coherence between strategic statements and present sustainable actions. However, in view of theoretical reference used, it was identified an imprecision in sustainability perspectives of decision making. Inconsistency tends to promote internal resistance, difficulty to commit to all areas and prejudice long-term results. Research limitations/implications Future studies should compare the decision-making meaning attributed to sustainability in companies of different market segments. Practical implications The studied case shed light on the importance of managers having at their disposal a map that relates strategic objectives and actions aimed at sustainability. The lack of this compromises the organizational results focused on corporate sustainability. Originality/value The understanding of the meanings attributed gives rise to perceptions of possible and relevant flaws in the alignment between the discourse and the practice of sustainability, supporting possibilities of the fine adjustments in strategic decision making.

Keywords: Sensemaking, Narrative analysis, Strategic decision-making, Organizational sustainability.

Sustainability in organizational context: Reflections on the meanings attributed to the decision-making process and its strategic implications at Itaipu

Universidade de São Paulo

New ways of understanding and addressing current challenges have emerged from the debate on sustainability that point to a need for managing opportunities and threats in a way that integrates the economic, environmental and social spheres. Managers must now interpret these changes in light of the new basis for decision making, and work on transforming them into opportunities for innovation within their organizations. This shift is driven by the growing support for premises of a sustainable society among parties now critical of “old” management standards based on profit at any cost (Savitz and Weber, 2007; Munck, 2013).

Companies may now issue statements on sustainability, but few are fully focused on actually implementing these principles (Munck, 2015). If we can understand the meanings and relationships between sustainability narratives and practices, we can then build up an identity of a recognized sustainable company, hence the justification for this study. Such an understanding would enable companies to strive toward meeting the conditions identified, after which they will be able to fine tune their decision-making processes in terms of investments, resources and results.

In order to be perceived as sustainable, companies must develop their decision-making processes, both respecting and adjusting their value systems and organizational arrangements. When companies select a sustainability approach that most conforms to their objectives, purposes and strategies, and begin adapting it to their particular social circumstances, it is natural to review the dominant values of the approach (Munck, 2013; Galpin et al., 2015). However, besides the definition of new visions, the challenge is to integrate traditional concepts of eco-efficiency/environmental management with those of sustainability, and to incorporate the latter into current administrative practice (Elkington, 2001; Hoff, 2008).

To achieve a more flexible and adaptable response to the demands of the macro environment, companies must manage strategies and products so that they meet intertemporal demands: a process that must be underpinned by an in-depth understanding of the past (Bansal and DesJardine, 2014; Munck, 2015; Elkington, 2001). Indeed, whilst decisions are made in the present, they involve a series of comparisons, conflicting interests and differences in terms of past and future: this is the context within which sustainability and strategy converge. Managers, for whom time is always a key factor, understand that the results of sustainability do not always play out in the short term, but concern rather the medium and long term.

In view of the above, it is clear to see the importance of planning and implementing sustainable action within the decision-making process in such a way that there is coherence and consistency between practice and individual understanding in terms of what is considered sustainable. Therefore, our question is: within a company recognized as sustainable, do the values and meanings inherent to the strategic decision-making process also change in accordance with the premises of sustainability?

Rese et al. (2010) pointed out the potential of narratives to define organizational practice and assign meaning to contexts, as a form of reflection on the company’s experience and a means of highlighting subjects’ interactions and conversations. In this way, individuals play a key role in assimilating the sustainability paradigm, as they make up the relevant social networks and the relationships between these, whether on a social, corporate or organizational level (Munck and Borim-De-Souza, 2009a). By interacting with each other, members of the organization interpret their environment and construct explanations for their experience that enable them to act collectively (Maitlis, 2005); and for Daft and Weick (1984), it is the role of managers to interpret, translate and assign meaning to events.

Studies on the strategic decision-making process, organizational sustainability and its respective attributed meanings point to the possibility of identifying key factors in the process of implementing sustainability (Póvoa et al., 2015). However, these factors alone are insufficient, as they rely on decision-making logic associated with sustainability, and managers do not always understand or take note of the meanings attributed to these decisions (Cavenaghi, 2016). A lack of reflection can induce people to associate sustainability and an individualistic vision, related exclusively to the organization’s survival (Silva et al., 2011, 2014).

As Herrick and Pratt (2013) demonstrated, the pursuit of sustainability by companies in the water sector involves a process of broad-scale organizational transformation, perceived as an emerging process that involves a number of deliberate procedures related to organizational factors, social value perspectives and projections about natural and environmental conditions. In other words, sustainable actions comprise new meanings and understandings, both on an individual and organizational level (Munck, 2015; Munck and Borim-De-Souza, 2009a, b).

Therefore, this paper aims to reflect on potential discrepancies between the meaning attributed to sustainability in the company’s strategic framework, and the meaning identified in the sustainability-focused actions outlined in currently active official and narrative documents. We sought to identify and discuss disparities of meaning and their implications for the strategic decision-making process. We used narrative analysis and data obtained from publically accessible materials linked with Itaipu (the company studied) and from semi-structured interviews. We did, in fact, identify a degree of correspondence between statements made during the interviews and the sustainable practices in place. However, in light of our chosen theoretical perspective, some discrepancy was evident between the current and desired decision-making process; a potential source of internal resistance that could compromise long-term results.

The objective of this section is to introduce the concept of “sensemaking” and its main qualifying characteristics as a theoretical alternative for studying sustainability. Careless managers, or those who adhere to the meanings currently prevailing in management, “tend to interpret social and environmental issues through the simple lens of cost and benefit analysis, requiring ‘only’ utilitarian calculations” (Munck, 2015, p. 533). The Triple Bottom Line approach proposed by John Elkington (2001) focuses, instead, on economic, environmental and social analyses; indeed, for the author, performance must be aligned with these three dimensions in order to guide companies toward sustainability.

Assuming that changes in one dimension will have economic, ecological and social consequences for all of them, this shift represents a perceptible development of consciousness. However, the literature examined reveals no single accepted understanding of the term “sustainability,” the meaning of which, therefore, is left to be constructed and created by means of an ongoing process of reinvention dependent on global demands and conceptual change (Herrick and Pratt, 2013; Starik and Kanashiro, 2013; Munck, 2015).

However, adopting a concept of sustainability is no guarantee that an organization is actually sustainable; it is necessary to acknowledge that organizations and individuals depend on the natural environment (Silva et al., 2011). Sustainable management involves more than the attempt to establish accepted meanings: it requires comprehensive approaches that reconcile different visions and respect the different time scales of the social, environmental and economic pillars of sustainable business (Munck, 2015).

This is because sustainable development seeks to achieve a steady balance between social, economic and environmental objectives, as well as to respect their interactions and different timelines; in other words, it serves to provide reference points and calls for strategic decisions in the organizational context to be aligned (Munck and Borim-De-Souza, 2009b). Further factors enabling significant advances in the execution of sustainable operations are the guidelines and values for resolving issues within the internal and external scope of the organization, i.e. different stakeholders (Herrick and Pratt, 2013).

In view of the understanding of sensemaking as an ongoing process that is subtle, swift, instrumental and social (Weick et al., 2005), the concept of building meaning fills gaps and serves as a guideline for action; this is because sensemaking provides the basis upon which meanings may be established, informing and restricting the construction of identity and its actions.

The properties of sensemaking highlighted by Weick (1995) serve as a tool for understanding collective action on an organizational level. Grounded in identity construction: it makes it possible to identify how meanings are constructed based on the past, i.e. it is retrospective; it, therefore, enables the creation of appropriate environments; consequently, sensemaking is social, because it is built around the interaction of individuals; and continuous since environments and perceptions are dynamic; therefore, it is focused on extracted cues; which then become relevant according to the context, i.e. plausibility.

Therefore, in order to deal with ambiguity, individuals seek plausible meanings that allow them to move forward, subjectively perceiving reality as endowed with an objective reality; intersubjectively legitimizing it and attributing it with meaning (Rese et al., 2010; Weick et al., 2005). In this way, organizations can be understood as systems of interpretation, within which managers are responsible for interpreting and translating formerly unnoticed events (Daft and Weick, 1984).

Consequently, sensemaking relates more to the interaction between interpretations than to the influence of current meanings on decision making. However, it is precisely on this point that the present study expands, making the assumption that the meaning attributed to the decision-making process has a significant influence on the effective scope of sustainability; because, in light of the fact that verbalized understanding and company structures have important strategic potential and that, in order to truly be implemented, strategy must be transformed into collective action (Rese et al., 2010), constructing meaning within decision-making processes depends upon the acknowledgment of a complex organizational interpretative framework for interpreting reality (Munck, 2015).

In this way, if organizations are made up of people with different world views, intersubjective engagement between these individuals is required in order to achieve strategic objectives; and, to this end, decisions must make sense for all those involved. Therefore, when addressing sustainability in the organizational context, what emerges is the need to understand the decision-making process in relation to the relevant set of themes and the understanding of meanings and values attributed to sustainability and related initiatives.

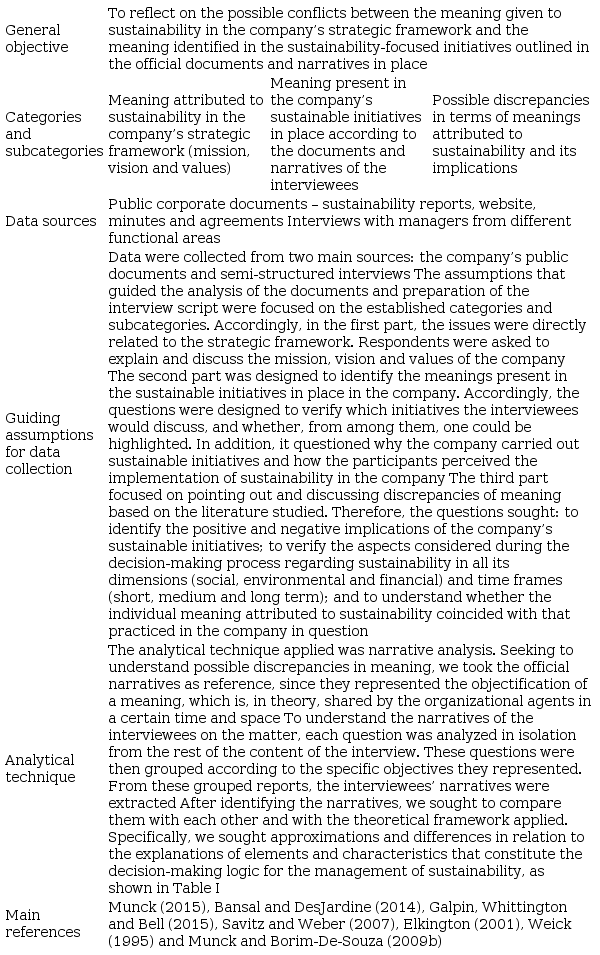

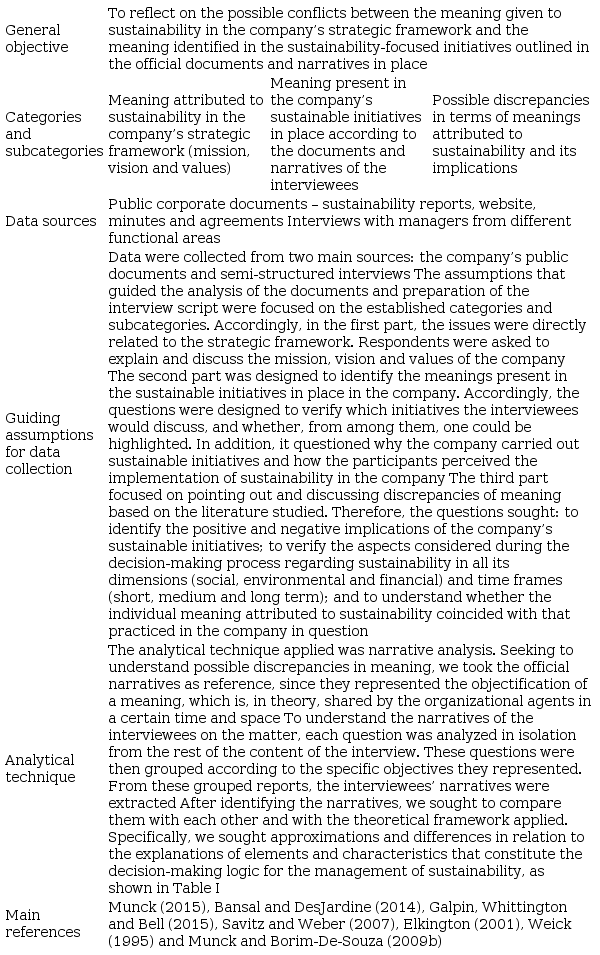

With the objective of reflecting on the possible discrepancies between the meaning assigned to sustainability in the company’s strategic framework and the meaning identified in the sustainability-focused initiatives outlined in the official active documents and narratives, this study takes a qualitative approach, being reflective and interpretative in nature and encompassing the complex phenomenon of sustainability in the organizational context (Creswell, 2014). Its scope is descriptive, in that it sets out to describe the characteristics of a particular population or phenomenon (Gil, 2006).

To confront the meanings associated with sustainability in the organization studied, narrative analysis was used to understand the organization, since narratives make it possible to organize the organizational practices whilst, at the same time, assigning meaning to certain contexts (Rese et al., 2010; Creswell, 2014). Thus, in view of the fact that organizations and environments must connect in order to exist (Weick et al., 2005), narrative analysis offers an opportunity to understand any deviations in meaning between action and practice, and makes it possible to seek new meanings for the decision-making process in organizations aspiring to be sustainable (Munck, 2015).

In terms of methods, this is a documentary study, in that it seeks to identify meanings attributed to sustainability in the documents available in the public domain (sustainability reports, the Itaipu Electronic Journal and information on the company’s public website). Furthermore, for data collection, this study also used interviews with managers from different functional areas, so that relevant data not described in the documentary sources could be identified, which contributed to our reflection on the meanings identified (Table II).

The company selection criteria were: Brazilian companies that completed the GRI report (Global Reporting Initiatives); with A+ level; recognized as sustainable between 2012 and 2014. The initiatives that corroborate this acknowledgment and demonstrate sustainability as a phenomenon to be managed in the organizational context were: the integration of sustainability into the strategic framework of the company; the presence of committees dedicated to discussing the related issues and sustainability-specific management program; national and international awards for sustainable practices.

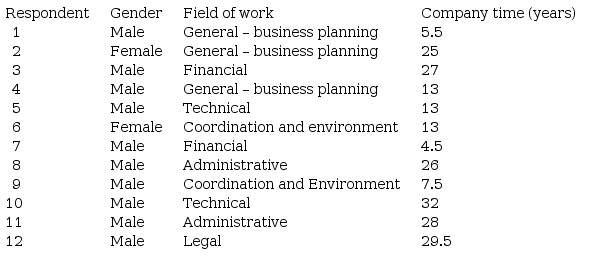

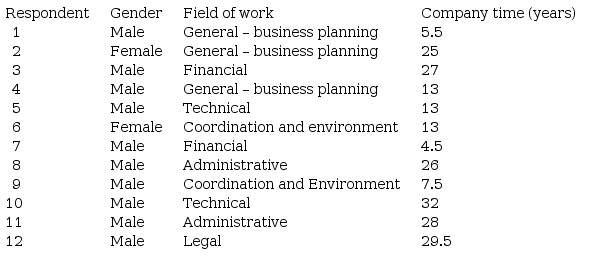

Next, we selected managers from various functional areas of the organization, whose work also related to sustainability initiatives. A total of 12 interviews were carried out: 7 in the company’s office in Curitiba, PR and 5 with the employees of Foz do Iguaçu, PR by video conference in December 2015 (Table III).

In order to protect the identity of the participants in line with the confidentiality agreement, the interviews were numbered 1–12 and identified accordingly as “Respondent 1,” etc.; they lasted 28min on average. For the interview in which recording was not permitted, simultaneous notes were made by the researchers.

This section of the paper will present the analysis and results found according to the objectives proposed and theoretical framework applied.

Itaipu Binacional, whose ownership and administration are shared between the governments of Brazil and Paraguay, was founded in 1966 by means of a diplomatic agreement between the countries for energy use in the region of the Ata do Iguaçu. The company is not profit oriented, but the annual revenue it obtains from providing electricity services must equal its costs exactly, thereby ensuring the economic-financial balance of the company.

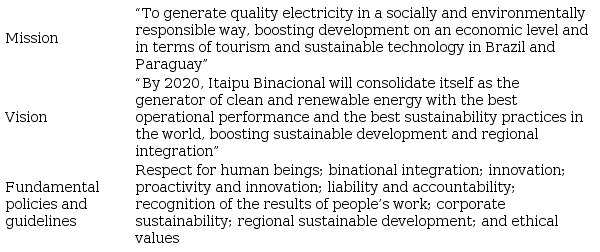

The company’s public documents highlight that, since 2003, sustainability as regards socio-environmental responsibility and development on an economic level and in terms of tourism and sustainable technology was officially included in the company’s mission. In 2005, by means of the notas reversais, these initiatives became permanent components of its energy generation activity. As a result of this commitment, in 2010 the company’s “Social Responsibility Council” was created and, in 2011, the group for the development of the “Sustainability Management System” (Sistema de Gestão da Sustentabilidade (SGS)) was established (Table IV).

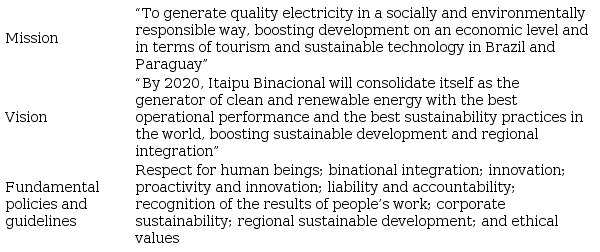

Our analysis of the organization’s strategic framework revealed the mission and vision of Itaipu to have elements that reflect the dimensions of sustainability proposed by Sachs (1993). The company demonstrates concern about economic sustainability, expressed in terms of operational performance; eco-social sustainability, embodied in the social and environmental responsibility the company assumed by embarking on this mission; and spatial and cultural sustainability, manifested in the company’s promotion of development and integration in the surrounding regions of Brazil and Paraguay.

In terms of vision, in the sense of “that which the company intends to achieve,” it was observed that Itaipu’s vision corresponds with the mission in place. Furthermore, we drew from this statement two objectives linked to sustainability, which take both the internal and external environment of the organization into consideration. They are, respectively, by 2020, to consolidate itself as a generator of clean energy with the best operational performance and the best sustainability practices in the world; and to boost sustainable development and regional integration.

The preponderant narrative extracted from the respondents’ interviews concerned the company’s mission to generate energy. However, the respondents explain that the organization’s responsibility would not be restricted to its final activity, because the mission itself “[…], shows that we need to integrate the question of sustainability into our practice” (Respondent 6).

They clarify the need for the company to be able to integrate and deal with sustainability both internally and externally. This can be observed in the following excerpt: “Today the company needs to worry about its primary activity, but it must also be concerned with the context in which it is situated. Itaipu stands out because it takes a complex view of its territory on several levels in order to achieve sustainable development” (Respondent 4).

However, the respondents report that they noticed social and environmental action even before any public commitment was made in the company’s strategic statement. From the interview content, we extracted narratives on the development of the surrounding environment: “Itaipu’s social programs are broad in scope: it has done a lot for the region, not only with the expansion of the mission, but through its work, in the region of Foz and Ciudad del Este primarily, as a driver of social development” (Respondent 10).

Galpin et al. (2015) explained that another factor to be considered in relation to companies choosing to adopt a sustainable approach are the values of the company: these are the basis upon which the organization will develop; they serve as the standards and expectations that define the proper behavior of employees in certain situations. At Itaipu, these values are called “Fundamental Policies and Guidelines” and are presented in Table III. It is worth noting that two of them relate directly to sustainability: “Corporate Sustainability” and “Sustainable regional development.”

The respondents pointed out the following values: concern for the environment and bi-nationality, sustainable development, respect for human beings and the participation and involvement of the agents in taking action. “Sustainability is a value […] to seek the development of the plant’s surrounding regions. It is no use being the largest producer of energy in the world, if there is a slum with people starving to death one kilometer away” (Respondent 12).

We recognized the possibility of interpreting these values in an interconnected way, since, from the moment the company became concerned with its surroundings, the parties involved were invited to participate in the subsequent initiatives. In this way, human beings are respected and organizational sustainability is aligned with sustainable development. Moreover, the company’s responsibility in promulgating changes in behavior in accordance with the relevant issues can be seen in the public narratives and in the perceptions of the respondents:

For us, essential values are an absolute must; a sine qua non of a company’s existence […] We must be proactive in our pursuit of sustainability, because sustainability does not exist without the right attitude. For example, the recycling bins are not enough: you need the right attitude in order to throw garbage in the right place

(Respondent 4).

This way, it is understood that sustainability, being integrated into the mission and vision of the company, makes action and projects possible, including in the surrounding region, and positively influences the system of which the company is part (Cavenaghi, 2016; Silva et al., 2011; Ostrovski, 2014). It is worth noting that Itaipu’s strategic framework incorporates the dimensions of sustainability linked to sustainable development, associated with strong commitment to conserving and respecting the region, not only in terms of the environment, but of culture as well, since the company is a binational.

As described in the company’s 2012 sustainability reports, Itaipu uses a “Business Planning and Control System” (Sistema de Planejamento e Controle Empresarial). This management model, which absorbs the management concepts of the Balanced Scorecard, was adopted to achieve the vision for 2020 and the company’s strategic objectives. To ensure strategy and operation are aligned, and to ensure that resources are managed in a coordinated way, the “Corporate Strategic Map” is divided into sectoral maps, according to levels of superintendence.

The strategic objectives adopted by Itaipu correspond to the themes proposed in its strategic framework and sustainability plan, for example, Objective 3 (“To be recognized as a world leader in corporate sustainability”) and Objectives 9 (“To promote tourism-related development in the region”) and 10 (“To consolidate the process of socio-environmental management by creating a watershed to conserve the environment and maintain biological diversity, whilst also integrating communities”).

Furthermore, the company uses a “Sustainability Management System” (SGS) to manage sustainability on an organizational level. Created in 2012, this encourages participatory discussion to identify and create synergy between initiatives, as well as to disseminate and instill a sense of sustainability among employees. It has its own structure, made up of four dimensions (corporate, environmental, socio-economic and cultural), which support initiatives and do not correspond with the hierarchical structure of the company. However, consultation of the documents revealed the extension of the system to incorporate the Paraguayan side to have only been approved in 2015, giving rise to the “Policy of Binational Sustainability.”

Since 2003, Itaipu has issued an annual “sustainability report.” Between 2003 and 2006, the documents were based on the “Social Balance” model. In 2007, the company adopted the guidelines proposed by the GRI and the electricity sector’s set of indicators. These reports are produced under the coordination of the “Social Responsibility Council” with the assistance of several employees in different departments; the Council contributes in terms of developing initiatives, the results obtained and the level of reporting.

The initiatives/programs highlighted in the sustainability reports consulted are presented in a clear and easy-to-understand way. The data reported are broken down as follows: corporate governance, the economic dimension, the social dimension (society and people management) and the environmental dimension.

The document is subject to external verification and formally presented to those involved with strategic planning and SGS; however, certain limitations in relation to the socio-environmental initiatives and people management can be identified. As explained in the “Reading Guide” at the beginning of the sustainability reports consulted (2012–2014), the initiatives in these dimensions comprise initiatives on the Brazilian side, and so it is not possible to say whether the positive and negative aspects of these initiatives are reflected to the same degree on the Paraguayan side.

In terms of the respondents’ perception of the company’s action for sustainability, the initiatives recalled pertained to the environmental dimension – “Cultivating Good Water” (Cultivando Água Boa (CAB)) and Biomethane – followed by the social – CAB, “Young Gardener” (Jovem Jardineiro), the “Friendly Waste Sorting” program (Coleta Solidária) and by sports. As explained in the interviews, it is not always possible to separate the environmental and social dimensions, since projects like Coleta Solidária have both a social and environmental impact.

These highlights may be associated with the nature of the company, the objective of its initiatives being financial balance rather than profit. For example, only two respondents cited the “Action of Sustainable Purchases,” under the economic dimension. In addition, the prominence given to CAB by the respondents may be related to the award received by the program in the national organization of the United Nations for “Best practices in water management,” in 2015, the year in which the interviews were collected. However, this does not belittle the relevance and impact of this program.

The CAB program is inspired by the public policies of the federal government and promotes a care-centered ethic, stimulating the adoption of new ways of being, living, producing and consuming. As stated in the corporate documentation, this program has led to a transformation in favor of sustainable development, as it involves community associations, city halls, cooperatives and environmental agencies.

With regard to this same publication, it is noteworthy that, in 2013, the “Production of Energy Supply” dimension was also incorporated. Furthermore, in 2014, development and innovation initiatives were added to this part of the study, such as the “Electric Vehicle” and “Renewable Energy Platform,” which, in previous years, were classified under the environmental dimension.

It was observed that, because the company’s primary activity depends directly on a natural resource (water), there is a degree of interaction between the environmental dimension and the production of energy supply; this is also expressed in the sustainability reports. It is, therefore, noteworthy that socio-environmental responsibility is interpreted as an extension of management, with the company’s concern about the practices and impact of its management being demonstrated in the action it takes; an attribute that differentiates it from other companies practicing activities of an environmental nature without increased commitment (Savitz and Weber, 2007; Hoff, 2008; Galpin et al., 2015).

The analysis of the company’s public documents – the SGS and fundamental policies and guidelines – revealed that the company defines sustainable action as “economically viable, socially responsible, environmentally correct and culturally accepted.” As for corporate sustainability, this was described as “ensuring that Itaipu’s initiatives are socially fair, environmentally correct, economically viable and culturally accepted, securing the long-term future of the company.”

In terms of the respondents, some of the meanings attributed to sustainability reflected Elkington’s (2001) Triple Bottom Line, such as an emphasis on working toward a state of balance, taking all dimensions into consideration in order to achieve organizational objectives. Others assign sustainability with a similar meaning to that proposed in the Brundtland Report, highlighting the engagement and relative commitment to conducting operations without compromising the ability of future generations to do the same.

Moreover, the interviews also revealed descriptions of concepts that were more particular in nature but related to the integration of sustainability into the organizational context. Among them, those that stand out are: an understanding of sustainability as a sort of competence, which would involve the ability to take a more complex “reading” of the environment, in order to act more safely and make less of an impact; sustainability as a factor that unites people and extremities seeking union; and the association between sustainability and the organization for the purpose of influencing changes in behavior. The following interview extracts elucidate these perceptions:

Explains sustainability using a metaphor, compares it to cement in the structure of the company. Because sustainability must bring together all the loose ends, margins and people, union is needed

(Respondent 8).

[…] I think it’s about rethinking […] a change of principles and values, basically, before a change of attitude. The first step towards sustainability is to change yourself: if you change your values and principles, this will be reflected later in your attitudes. And, if it is reflected in your attitudes, it is reflects in your attitudes as a citizen […]

(Respondent 6).

[…] what led the company to worry about sustainability was not just the fact that this was an emerging, current and unavoidable issue; the company was also taking its own influential capacity into account

(Respondent 7).

What is observed is the existence of concern regarding sustainability associated with the organizational context and with individuals; indeed, as affirmed by Munck and Borim-De-Souza (2009a, p. 3) “the legitimacy of a sustainable paradigm will only happen when human beings, represented as social, economic and organizational agents, validate this whole scenario.”

When asked whether their understanding of sustainability matched that proposed by the company, most respondents said it did. However, they pointed out a limitation in the understanding of sustainability by employees, with the presence of resistance at various hierarchical levels, and a general systemic lack of understanding of the topic.

Póvoa et al. (2015) identified this resistance as part of the process of implementing sustainable corporate management at Itaipu Binacional itself. This process can be divided into two stages. The first, from 2003 to 2006, is identified as a learning process on the significance and implications of engaging in sustainable projects, which at that time were centered on socio-environmental issues and ended up generating a degree of reluctance, being considered a “fad” by certain parties. However, in the second stage, from 2007 to 2012, which saw the adoption of the GRI, the question of sustainability developed an economic dimension, which promoted the understanding of the execution of the initiatives and began a dialogue with society.

If we consider its insertion into the company’s mission in 2003 by the president of the organization, as well as the subsequent alignment of strategic objectives with it, we might observe that sustainability was integrated as a strategic factor in the structure of the company in a top-down way. Galpin et al. (2015) explained that every successful cultural shift involves approaches at various levels of the organization, and sustainability is no exception. Accordingly, as regards the sustainability reports, the creation of the SGS and the systematization of action in the form of projects, it may be observed that the implementation of sustainable initiatives prioritizes interdisciplinarity and horizontal integration among the individuals in the organization.

However, during the interviews, when asked about the aspects considered during the company’s decision-making processes in relation to sustainability, there were divergences in the responses of the participants. For some, economic, social and environmental aspects were considered equally important. However, others perceived that, at certain times, social and environmental aspects stood out and, at others, economic matters were more prominent.

The respondents emphasized that “economic,” for the company, means the economic-financial balance of its activities, not being driven by profit. However, this makes it necessary, for certain decisions, to opt for the alternative that provides the most noticeable results, usually measured quantitatively over a restricted period – short/medium term:

[…] because we deal with public money, we need to be very careful, because when investing in innovative projects there is always a risk factor, which is not always possible to measure, because there are things that can cost more or even make the project impossible. Therefore, whilst Itaipu Binacional is a development proponent, it is also questioned about its investment in socio-environmental issues

(Respondent 2).

At the level of strategic planning, I still notice a tendency for the financial, the economic. […] the priority in the allocation of resources is for things that have a result people can see, but in terms of change, this is not always possible […] with culture, the result will be medium and long term. […] But, the fact of having the concept of sustainability in the mission and a system linked to strategic planning is already a huge opportunity, because it is stated; it is written

(Respondent 6).

I think the social and environmental part is even the highest priority, maybe. But of course, I don’t mean that Itaipu is irresponsible and doesn’t measure value, but it really thinks a lot: if something is good, then we’re going to invest, we’re going to do it

(Respondent 11).

Regarding the criteria and choices related to the decision-making process as regards sustainability, the following aspects were identified in the interviews: the relationship between the executed action and the intended action, strategic alignment and the impact it generates. It was cited that an initiative is expected to reach a certain level of maturity before a new one may begin. The company also tries to identify how a new initiative might contribute to those already underway:

We look for those decisions that would contribute the most to the initiative or program that is already established […] It would not be right to start another project without the former being consolidated in this pre-established structure, so we seek to optimize what already exists

(Respondent 3).

As regards classifying initiatives by their relative dimension, as had been explained, it is not always possible to completely separate them, because at times they come under more than one dimension, for example, both environmental and social, “[…] Every initiative in one dimension or another ends up having repercussions on or interaction with other dimensions. So, when we think, we categorize it according to the scope that best corresponds and check its relationships with the other dimensions” (Respondent 1).

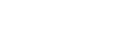

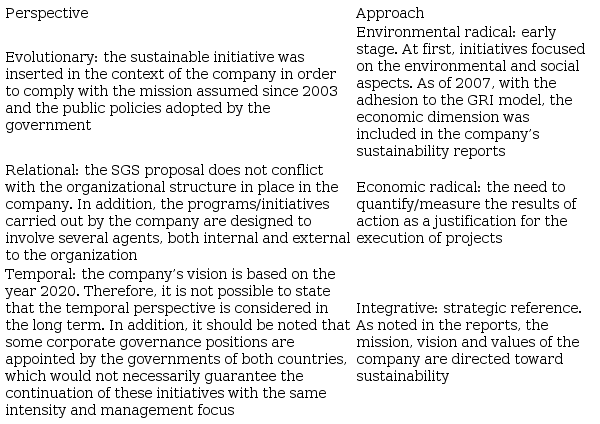

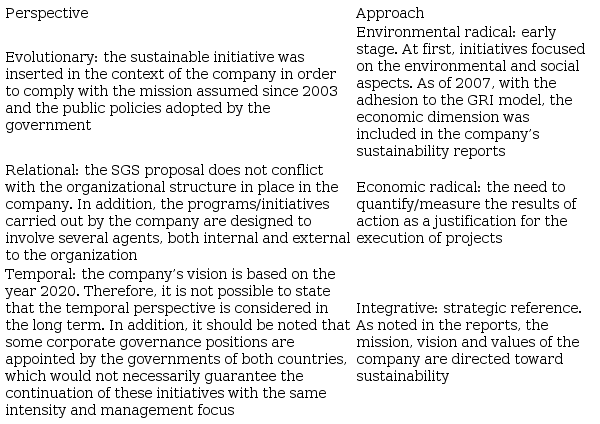

We can, therefore, infer that there is a certain logic to be followed in decision-making processes that regard sustainability. However, they are not always perceived in the same way by those involved, as biases exist that interfere with human behavior, and each situation has its own distinct characteristics. At the same time, taking Table I as an example, it was noted that some reports demonstrate a tendency toward an integrative approach, while others may be classified as falling somewhere between the environmental and economic radical, as in Table V. In terms of timeframe, evaluations are predominantly short and medium term in scope, considering that the company’s vision is outlined as far as 2020 and that the outcomes of actions should be evaluated quantitatively.

As regards the positive aspects of sustainable action, respondents reported that benefits include the following: they create a staff body with an enhanced world view, who promote sustainability outside the organization as well; pioneering action to enhance and empower the region, which promotes development; more operationally efficient; acknowledgment of society; the influence and impact of activities have a broader impact; and the scope of the corporate vision.

In terms of the negative aspects of sustainable action, respondents said they struggled to see any, identifying a number of challenges instead, among which they highlighted: internal resistance to cultural change; people’s awareness; measuring the results of initiatives; the cost of initiatives (since, in certain circumstances, the short-term costs are high and the company must ensure its economic activity remains balanced); and, working with society, because you have to demonstrate the limits of the company’s activities to society, as well as listen to society before launching any initiatives.

When asked about the benefits and challenges of sustainable action, the narratives of the respondents show that, whilst the company is choosing to implement these initiatives, there is a degree of internal resistance to change that must be worked on. This resistance can be minimized by illustrating and highlighting to employees the results that the company obtains by adopting a sustainable approach. In this way, the tendency is for them to understand that impacts take place both inside and outside the organization and, therefore, interaction and cooperation between the actors involved, the stakeholders, is important (Osorio et al., 2005).

Póvoa et al. (2015) noted that, despite the fact that Itaipu employees were trained and qualified, resistance to change consisted specifically in incorporating the principles of a sustainable management model, constituting a significant obstruction to the sustainability program. This challenge reflects the nature of sustainability itself: as it transcends the “fad” phase, a whole new paradigm is developing that recognizes systemic complexity and the inequalities and imbalances that can compromise sustainability (Bansal and DesJardine, 2014).

Therefore, it is possible to identify the need for greater understanding of the meanings attributed to sustainability among employees in different hierarchical positions and functional areas, particularly in view of the fact that sustainability requires an adaptable and flexible management team capable of supporting conscious processes that respect learning cycles and technological, procedural and political feasibility (Herrick and Pratt, 2013). The perception of the meanings associated with sustainability among individuals in the organization form the basis upon which to implement initiatives that direct and strengthen the identity of a sustainable company (Munck and Borim-De-Souza, 2009b; Rese et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2014; Munck, 2015).

Returning to the question that guided this study – whether, in a company recognized as sustainable, a change of values and meanings in the strategic decision-making process also occurs to align them with the premises of sustainability – it was possible to infer, from the narratives presented in Itaipu’s decision-making process, the predominance of the environmental radical approach, oriented by a relational perspective, placing the company exactly in the central region of Table I.

The sentences that describe the mission and vision of Itaipu present a meaning attributed to sustainability similar to the one proposed by Elkington (2001) and Sachs (1993), involving the spatial, cultural, social, environmental and economic dimensions. These perspectives support the sustainable actions of Itaipu, as reported on the model proposed by the GRI. Sustainability is inserted in the strategic framework (Galpin et al., 2015), but it is not possible to say that all dimensions are understood and considered with the same relevance or concurrency.

The environmental radical approach is very close to the context of the organization’s performance and is present since the early stage of the formal adoption of sustainability in the public declaration of the company’s mission in 2003. In addition, it is associated with the direct impact that this dimension exerts on the company’s primary activity, because for the hydroelectric plant to achieve its vision, Itaipu Lake must to be preserved.

The execution of initiatives depends on the involvement of different agents, but the need to quantify the results, to justify them, prioritizes benefits in the short and medium term. At this point, we can identify a relational perspective, and the time factor, highlighted as one of the fundamental elements for sustainability (Munck, 2015; Bansal and DesJardine, 2014; Sachs, 1993), can be compromised, particularly impairing long-term organizational sustainability due to the pursuit of more obvious results in the short and medium term.

In light of our results, and considering the framework proposed by Munck (2015), it has been observed that Itaipu is in a phase of renewal, whereby sustainability is gradually being integrated into management and decision-making processes. The respondents show knowledge of sustainability and its pillars, but they differ in terms of the respective prominences of each one in the decision-making process. It is possible to identify, based on the interviews, reflections on the current meaning, but there is also an absence of consensus to guide the decision-making process.

The coexistence of several approaches to sustainability is a factor that influences internal resistance to the integration of sustainability into the organizational context. This realization presents consistent information on the path that the organization must follow until it reaches a consensus on its narrative for sustainability, as proposed in this study, which is the convergence of an integrative approach with the temporal decision-making perspective (as shown in Table I), considered ideal as a guideline for organizations wishing to achieve sustainability in its most comprehensive form.

Therefore, adopting an understanding of strategic action as something that people and organizations perform and not as something organizations have (Rese et al., 2010), the decision makers and agents involved may experience difficulties in prioritizing sustainability-related goals and actions if these are understood in the same way. Therefore, this confirms the importance of understanding the processes of building meaning – sensemaking – to make the meanings attributed to sustainability understood, and to change them if necessary.

Based on interaction with the different actors involved, one can mitigate possible conflicts of interest between the functional areas and projects focused on sustainability, as well as make employees understand why they should or should not adhere to sustainability in the organizational context in its fullest sense (Weick, 1995; Daft and Weick, 1984; Weick et al., 2005). Accordingly, “it would not help the director of marketing and sustainability to say that he is acting from an integrative and temporal perspective, if the financial and operational areas are acting from an economic radical and evolutionary perspective” (Munck, 2015, p. 534).

We note the need for timely action, particularly with the internal public, aimed at disseminating and building meanings attributed to sustainability that are plausible for the majority of employees; as well as at coordinating and evaluating approaches and perspectives that guide the decision-making process with regard to sustainability. In this particular case, it is observed that Itaipu has at its disposal a map illustrating the dominant narrative as well as the means of achieving an integrative and temporal approach for its decision-making process.

As a suggestion, future studies should compare the meanings attributed to sustainability in relation to decision making in companies from different market segments and, even, in different functional areas and hierarchical levels. These data would encourage the adhesion to sustainable initiatives by also contesting meanings adopted in relation to organizational outcomes (financial, clients, etc.).

Descriptive framework of the possible ongoing narratives that may support the sustainability decision-making process

Munck (2015, p. 532)

Research operation protocol

Prepared by the authors

Profile of the respondents

Prepared by the authors

Itaipu’s strategic framework

Prepared by the authors from the company’s sustainability report

Summary of decision-making perspectives and approaches to sustainability identified in the company

Prepared by the authors from Munck (2015)

Descriptive framework of the possible ongoing narratives that may support the sustainability decision-making process

Munck (2015, p. 532)

Research operation protocol

Prepared by the authors

Profile of the respondents

Prepared by the authors

Itaipu’s strategic framework

Prepared by the authors from the company’s sustainability report

Summary of decision-making perspectives and approaches to sustainability identified in the company

Prepared by the authors from Munck (2015)