The coaching process seen from the daily (and controversial) perspective of experts and coaches

Revista de Gestão, vol.. 26, no. 2, 2019

Universidade de São Paulo

Abstract:

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to analyze the coaching process as perceived by experts and coaches, addressing its routine aspects and areas that are object of dissent in the organizational field.

Design/methodology/approach

Qualitative research conducted through interviews with 20 experts and coaches who work in Portugal.

Findings

Lack of consensus on conceptual approaches, few demands from organizations for concrete results, and elitism due to its selective use for high-level professionals. There is an expectation of companies that adopt a “coaching culture,” which includes participative actions, dialogue and humanization of relationships. There are benefits for organizations and professionals that result from its application, which raises care in considering it just another management fad.

Originality/value

Professionals and organizations are increasingly adopting coaching processes, but there are few academic studies, with a scientific view, and more rarely from the perspective of practitioners (coaches). Hence, this topic lacks a more accurate approach, to better understand its application and extend the debate on controversial aspects, in order to make the discussion on its value more consistent.

Keywords: Portugal, Coaching, Human resources.

1.Introduction

The main objective of this study was to analyze the coaching process from the perspective of experts and practitioners (coaches), addressing daily aspects of its practice, as well as controversial elements in the organizational field. It also examined the role of Human Resources (HR) professionals and departments, regarding their knowledge and monitoring of this process when hiring such services for their organizations. This objective also included underlying reflections on whether (or not) HR departments have evolved to become strategic units in the organizations, or remain as an operational and bureaucratic area. In addition, we aimed to expand the discussion, in academic terms, to understand this recent and complex subject (Laville & Dionne, 1999) that has gained relevance in the labor market, but still lacks an appropriate scientific support, being often considered a fad (Johnson, 2007).

We conducted the empirical research in 2017, based on 20 interviews with experts and professional coaches with knowledge and experience in the Portuguese organizational context and in other European countries, as some of them work in France, Germany, England and Spain.

We chose Portugal for the study given the cultural and linguistic proximity to Brazil, and the similar trajectories of the two countries in this field. Both saw the emergence of the coaching process in 1995, which has much increased after 2005, and experienced similar crises in their markets, which affected the hiring of coaching processes.

While in Portugal there is an effort to consolidate professional practices and its scientific development (Barosa-Pereira, 2008; ICF Portugal, 2016), a recent study in Brazil (Batista & Cançado, 2017) shows that there is no national regulatory body, with different institutions seeking to structure the professional activity and the academic education. The greater institutionalization of coaching in Portugal led to a better understanding of this context, contributing to scientific research in Brazil.

Portugal has experienced important changes in the labor market, and suffered the consequences of a crisis that led to a major economic slowdown (Rodrigues, Figueiras, & Junqueira, 2016). This resulted in a negative gross domestic product (GDP) performance, between 2004 and 2014, and a decline in household consumption expenditures by 64 percent of GDP in 2014 (INE/PORDATA, 2017). Unemployment rates also increased from 7.6 to 12.4 percent, between 2008 and 2015, above the EU average value of 9.4 percent in 2015.

This context brought greater job insecurity and increased levels of dissatisfaction, as observed by Amorim (2015) for the Brazilian labor market, and a similar result for Portugal, according to Matos and Domingos (2014).

This situation strengthened the need to introduce new management strategies for HR, to better ensure the engagement and retention of professionals, especially those who are critical for business competitiveness. Coaching thus emerges as an alternative, mainly in cases of leadership development (Underhill, McAnally, & Koriath, 2010) and their teams. The importance of coaching for professionals and organizations is demonstrated through the acceleration of professionals’ development (Nieminen, Smerek, Kotrba, & Denison, 2013) and the higher level of satisfaction within companies (Whitmore, 2010; Goldsmith, Lyons, & McArthur, 2012). The increase of employees’ personal and professional levels leads to improvements in organization performance and market competitiveness. These are actions about people’s management; hence, it is necessary that HR professionals be more active and in line with business strategy and results, since coaching has been adopted as a management philosophy and not a specific development action in organizations (Hwang & Rauen, 2015; Joo, 2005).

Conceptually, coaching is a process in which a specialized professional (coach) helps the customers (coachees) to develop strategies for improving their performance in the organization (Whitmore, 2010) This process is supported by instruments that facilitate self-knowledge, learning and reflection on their potential, and define actions to achieve goals (Latham & Stuart, 2007). This relationship is often intermediated by HR departments, as the hiring party.

Although increasingly used by professionals and organizations, coaching is a frontier issue in academic studies. This is one of the main reasons for addressing it: it has been object of controversy, and considered a management fad (Wood & Paula, 2006), subject to judgments regarding its use and results (Milaré & Yoshida, 2007; Wood, Tonelli, & Cooke, 2011). Even in the most recent studies, opinions remain the same, although there was a wide diffusion of the theme and expansion of its practice. Batista and Cançado (2017) and Rocha-Pinto and Snaiderman (2014) consider it a field under construction, with conceptual dissent and market expansion. Academic research has not followed the pace.

In this regard, Micklethwait and Wooldridge (1998) argue that some organizational practices are first adopted in the market, and later studied at universities. This seems to be the case with coaching, whose practical literature and user manuals are more abundant than scientific papers (Johnson, 2007; Orenstein, 2002), which are scarce, possibly because of its stigma among academics. Therefore, its recency and complexity increase the responsibility for conducting studies (as a typical topic of applied social sciences), to better serve the market as final user (Fischer, 2001).

2.Theoretical framework: the coaching process

Our theoretical approach sought to understand the relationship between people strategic management and coaching as a human development process. The discussion about the (non) evolution of HR departments as strategic units in the organizational context serves as background for this perspective. Since coaching is a recent and different approach to traditional human development actions, HR professionals and departments, supposedly strategic, should be familiar with its implementation, monitoring and benefits for the organization.

2.1.Strategic management of people: analysis of its (non) evolution

This discussion about the supposed evolution of HR departments as more strategic units is not recent. Souza (1979)already indicated how HR departments were changing their names (e.g. talent management), without an effective change in practice, and so did Souza, Calbino, and Carrieri (2010).

The literature on this topic, although it discusses the importance of this strategic and business-related action, shows that this new positioning is not a real fact. There is a dichotomy between the speech of a modern HR area and a still operational and reactive practice (Boxall & Purcell, 2011; Brewster, Mayrhofer, & Reichel, 2011; Legge, 2006; Ulrich, Ypunger, & Brockbank, 2008; Wood et al., 2011).

Several studies on human resources management (HRM) indicate the need for interaction with the organizations’ strategies (Ulrich et al., 2008). The idea of a strategic HRM should consider its alignment and influence on organizational decisions (Schuller, 1992), and the measurement of its financial contribution to company’s earnings (Brewster, 2007). In addition, it should be a source of competitive advantage (Fischer & Albuquerque, 2005), keeping the excellence of its operational activities (Legge, 2006), and articulating the HRM dynamics with the labor market and work relationships (Delbridge, Hauptmeier, & Sengupta, 2011).

In the case of Portugal, crisis’ intensification in 2014 and political, social and economic changes (Rodrigues et al., 2016) affected HR departments and professionals in the job market. There was a dismantling of structured HR departments, centralization of actions in organizations’ headquarters, extinction of HR departments in local units, and reduction or suspension of investments in development programs (Dominguez, 2016). Nevertheless, professionals and organizations increasingly used coaching as one of the answers for meeting competitiveness demands in the job market (João, 2017).

2.2.Understanding the coaching process

To understand the coaching process from an academic perspective is a stimulating and necessary challenge. From the outset, it is hard to point the origin of the term “coaching” (Joo, 2005; Kampa-Kokesch & Anderson, 2001). According to Barosa-Pereira (2008) and Witherspoon and White (2001), it ranges from comparisons with the Socratic method to references to “coche” (a particular type of carriage), passing by its association with sports (Araújo, 2010).

The first coaching schools emerged in the 1980s, and during the 1990s they started to enter companies (Lages & O’Connor, 2010). Their growth began in 1995, through the creation of the international coaching federation, a global organization for gathering professionals and their popularization spurred the growth of training and certifications (Ferreira, 2008; Coelho, 2016). Since the 2000s, we have observed the increase, although slow, in international scientific production (Kampa-Kokesch & Anderson, 2001; Grant & Cavanagh, 2004; Kets De Vries, 2005).

Hodge (2016) carried out a bibliometric survey between 2003 and 2012, showing that the body of knowledge in the area was still incipient. He published the paper in one of the few scientific journals focused on coaching, the International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, published since 2003 in Oxford. He observed that most of the authors were from the UK, the articles were mainly about coaching (vs mentoring), and their content was mostly developed in the business context.

These results may indicate that the organizational field is undergoing a process of institutionalization, according to DiMaggio and Powell (1983) definition, where isomorphism mechanisms are developed for new practices, such as the coaching process.

Although there are many concepts of coaching (Batista & Cançado, 2017), the main approaches are: to unlock a person’s potential and maximize his/her performance (Diedrich, 2001; Goldsmith et al., 2012); to support him/her in focusing on practical actions, planning, and achieving goals and wishes (Coutu, Kauffman, Charan, Peterson, Maccoby, & Scoular, 2009); to be a systematic activity based on method (Milaré & Yoshida, 2007), which enables the organization of thoughts (Goldsmith et al., 2012); and to increase self-knowledge and well-being (Cavanagh, Grant, & Kemp, 2005; Rocha-Pinto & Snaiderman, 2014).

Coaching favors career growth by leveraging a professional relationship through a process of observation, reflection, inquiry, dialogue and discovery, enabling the professional to achieve better results (Witherspoon & White, 2001). This works through a process that follows several stages (although there are variations): arrival of the request and the question “why coaching?”; hiring; creating a context and establishing results; sessions; between sessions; evaluation of the process; and closing and feedforward (Resende, 2016).

Several resources are used to develop the process between coach and coachee, including the so-called “powerful questions” (that mobilize the coachee’s reflection), the use of assessment instruments (personality inventories) and the use of feedback. All of these are tools that disclose to the coachee traces of his/her behavior and beliefs.

2.3. Controversial content related to the coaching process

There are common points in the different approaches, as well as issues that merit deepening, because they are not consensual or have no consistent bases for conclusions. One of them is that the process is not numerically and formally measurable regarding its results (Lange & Karawejczyk, 2014; Melo, Bastos, & Bizarria, 2015), which is a cause for concern.

Another point refers to the confusion between coaching and other interventions, such as mentoring, counseling, consulting, psychotherapy and traditional training. The major difference is that the coach does not direct the coachee’s decisions for action, since in coaching there is no such orientation. In addition, there is a partnership relation, which assumes the coachee’s co-responsibility for results (Andrade, 2016; Barosa-Pereira, 2008; Whitmore, 2010).

There is usually a distinction, without full consensus, between the types of coaching, such as executive coaching, career coaching, life coaching and team coaching. These approaches do not necessarily differ in their practice, but are used as an explanation to the market of the different types of intervention (João, 2017).

Another frequent discussion about coaching processes refers to how adequately they are driven by outside consultants or by professionals that work in the organizations’ HR departments. Battley (2006) examined the advantages and disadvantages of both, emphasizing that the use of organization’s professionals requires additional care for risks. In other words, how reliable is a HR professional to keep the confidentiality of conversations, being a company’s employee? There are also conflicts of interest and the lack of prioritization of coaching actions over regular daily HR activities (Campos & Pinto, 2012; Wood et al., 2011).

An additional item that deserves attention is the training of the leader for the role of coach (Leader-Coach), since this can generate concomitant benefits of growth for the leader and the team (Campos & Pinto, 2012; Goldsmith et al., 2012; Graziano, Peixoto, Pizzinatto, & Castro, 2014). The dispute arises because some authors consider that leaders should not act as coaches, as they need to direct the behavior of their team. Others believe that the empowerment of leaders with coaching techniques can help them take participatory actions and influence their team by making them more reflective, so that they can seek solutions based on their own experience.

There is also a topic that emerged from the interviews, but is little identified in the literature: the “coaching culture.” Hwang and Rauen (2015) briefly address it, when discussing the development of skills and multiple working styles, including cross-sectional projects that can accelerate learning. Thus, it strengthens the conception of policies and practices of people management, based on a less functional and immediate formation (Parente, 1996), more focused on the individuals’ development potential.

3.Methodological procedures

The lack of theories about coaching, together with the defined objectives, led to a qualitative research, according to Creswell (1997).

3.1. Data collection

Data collection procedures began with the bibliographic research stage that consisted of a survey of Brazilian scientific journals in electronic databases, by using the keyword “coaching,” from 2007 to 2018. As main findings, we identified 70 articles at the Journals database of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), 12 at the Scientific Periodicals Electronic Library and 19 papers at the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO). However, the majority of articles focused on health, psychology and sports. We found few articles on the specific topic, which proves a scarce scientific production, and confirms the findings of Batista and Cançado (2017), who searched the proceedings of the annual Conference of the National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Administration (EnANPAD) and found only five publications between 2007 and 2016. As an example of the scientific production gap, just in the year 2017 the same number of articles (five) was published at EnANPAD as in the previous ten years. This shows a growing interest in the subject.

We used semi-structured interviews to collect data, according to Guerra (2006). They were developed from the first contacts in this field and from the bibliographic review.

3.2.Characterization of respondents

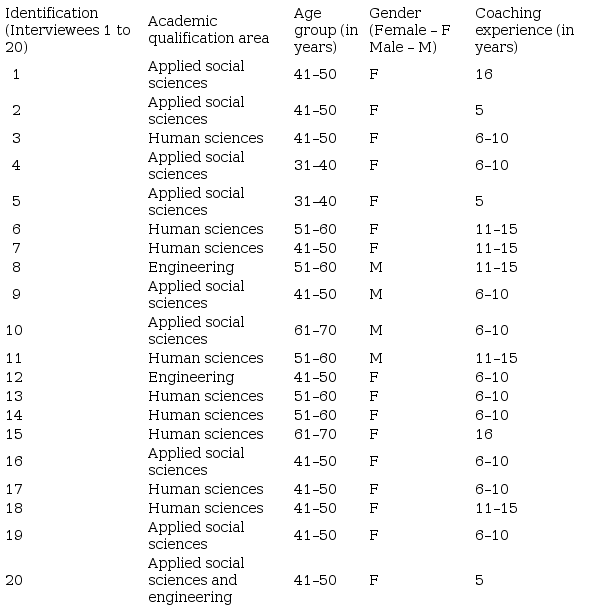

We conducted interviews with 20 experts and/or coaches, in Portugal, as shown in Table I. Respondents are in chronological order of the interviews, and names and other attributes were omitted to safeguard their identities.

According to Biernacki and Waldorf (1981), we adopted the “snowball” technique, in which it is essential to include people with experience in the subject under study. We asked respondents to indicate people with experience in coaching, who could take part in the research. We made contacts first by electronic message or by telephone, in order to align the schedules of professionals and researchers.

All had one or more of the following characteristics: independent coaches in organizations; facilitators in training programs on coaching; business consultants who had undergone qualification and a coaching process; certifiers of coaching programs; authors of books on the subject; university professors of the discipline “Coaching Processes.”

The group of interviewees included 16 women and four men, with ages between 38 and 62 years old, which may indicate maturity in choosing the subject. All of them had more than five years (up to 16) of practice in the area, with previous experience or still working as consultants or professionals in HR activities in organizations.

In terms of higher education, their main areas were applied social sciences (nine people), especially sociology and management, and human sciences (nine), with emphasis in psychology; there were also cases of engineering degrees (three people, one of them also graduated in applied social sciences). It should be mentioned that there is no specific degree required for education and certification as coach.

The respondents received the invitation for interview with interest and curiosity. As the majority said, studies on the subject in the academic environment are unusual, which strengthens the original proposal on the relevance and need for more in-depth studies. In addition to the interviews, they could participate in events (lectures, workshops and meetings), where they could extend their understanding of the Portuguese context and of the proposed topic.

3.3. Data analysis: definition of controversial areas and their dimensions

As for data analysis, we adopted Minayo’s (2001) proposal, who emphasizes that this stage requires great attention, because it serves the purpose of establishing an understanding of the collected data and responding to the proposed objective. Working with categories means defining clusters of ideas around a particular concept. The concepts used to analyze the interviews’ content come from the literature review.

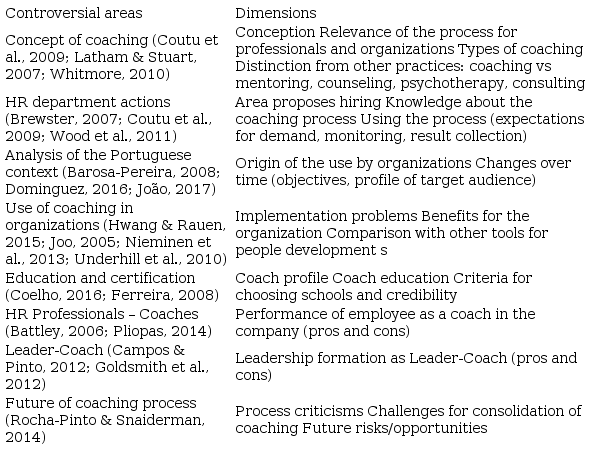

According to Bardin (2011), the content analysis method leads to the study of the motivations, attitudes, values, beliefs and trends, allowing greater depth and complexity in the analyses. Through this technique, we identified the categories in the literature that favored their crossing with data from the interviews. Table II describes the categories and dimensions used. We recorded the interviews on a notebook with the respondents’ consent, and then classified them according to the analytical model of Table II.

3.4. Methodological limitations

The study of phenomena that involve human beings can lead to biases, such as the indirect influence of the researchers, through their focus either on certain results or on their methodological choices. In addition, this type of research deals with a recent topic, subject to professional experiences not firmly sedimented. Another limitation refers to the use of only one perspective, the viewpoint of those who conducted the process or studied it (coaches and experts), without investigating those who underwent it or hired it (coachees and HR departments). In addition, the small number of interviews could be a limitation, but it was quite satisfactory if we take into account the information saturation criterion, as discussed by Bauer and Gaskel (2002).

4.Description and analysis of results

Results are presented and discussed based on a set of analytical categories built in a process both deductive, from the theories used, and inductive, by bringing out new categories. We used excerpts from statements, whenever they were relevant to exemplify a situation, or when it was an opinion shared by other respondents. We adjusted some expressions for better understanding and ease of reading, taking care not to change their meaning.

We sought to establish links between the content of the answers and the analytical model of Table II, as well as with the theoretical framework used.

4.1. Controversial areas and their dimensions in the coaching process

4.1.1. Understanding the concept of coaching

The lack of one single concept of coaching is evident, although there are common elements among the respondents. Proposals such as “supporting the coachee in his/her self-knowledge” (Interviewee 2), “ensuring that the customer recognizes his/her potential and possibilities” (Interviewee 3), and “strengthening the need to define a plan of action to achieve the desired goals” (Interviewee 5) are present in the concept’s formulation. This lack of uniqueness reinforces the arguments of Latham and Stuart (2007). The disclosed contents confirm the conceptual approaches of Whitmore (2010) and Coutu et al. (2009).

The 20 respondents stressed the benefits of the process for organizations and professionals. However, there was an emphasis on constraints, which warned about the process contingencies. These were: “the organization needs to understand what is coaching, in order to align expectations with possible outcomes” (Interviewee 4); “the coachee must wish to experience the process” (Interviewee 5); and “the coach needs to be well selected, because there are all types of professionals, as in any occupation” (Interviewee 9).

Regarding the types of coaching, there is a consensus that the essence of the process focuses on the person. The established types “exist and are not standardized, but are more “didactic” (Interviewee 6) or “market-driven” (Interviewee 9), in order to explain that, in practice, “coaching is coaching!” (Interviewees 6 and 9). As they point out, “it does not matter if the demand is for career, life coaching, or better communication as a leader, because the employee being served is unique, and not divided into “person,” “leader,” “husband” or something like that” (Interviewee 7). This aspect is also strengthened by Interviewee 13. In addition, “the coaching process is the same, and needs to be adapted for types of customers and not for types of coaching” (Interviewee 2). This approach is consistent with João (2017).

However, it is worth highlighting an issue that emerged from the interviews and was not part of the script, regarding the difference between the “process” of coaching and coaching as a “tool or technique.” Respondents emphasize that “coaching is a process that has an expected sequence, assumes concrete results, and takes place over a period of time and not just during meetings” (Interviewee 3). Tools are used “when the coach decides to employ some instrument, such as a personality inventory or a technique for future visualization” (Interviewee 7). This content is further reinforced by Interviewees 11, 14 and 19.

The differences between coaching and other types of intervention are a thorny issue. Although there is a defined methodology as a basis for coaching, there are professionals who “adapt the use of coaching or call coaching what they already do in consulting or mentoring, by giving suggestions and solutions. And that’s not coaching!” (Interviewee 4). According to Interviewee 16, “there are professionals who call themselves coaches, but who give instructions on what to do, and determine the next steps of the coachee,” which deeply distorts the reflective and self-knowledge process of coaching.

Some respondents highlighted the confusion with psychotherapy, which provoked outrage, such as related by Interviewee 6: “it is the worst of all mixtures, because people think it is necessary to be a psychologist to become a coach. Psychology works with the past and coaching looks at the future. This happens because some coaches defend the idea of a “Psychological Coaching,” which is already a distortion of the coaching essence. Indignation increases in the Portuguese context, because of the “emergence of a costly debate about the need for coaches to be qualified in Psychology, an unreasonable proposal nurtured by class entities” (Interviewee 17). This controversy between the approaches restates the propositions of Barosa-Pereira (2008), and is a subject of concern for professionals.

4.1.2. Action of the human resources department

When asked about the HR department of organizations being a coaching contractor, and the extent to which its professionals are familiar with the process and follow it, respondents had different opinions. However, there was a common ground: HR professionals from large companies (usually multinationals) generally have a greater knowledge of coaching, while those from smaller organizations do not master the process, “although they have heard that coaching is a current issue in the media today” (Interviewee 10).

In large companies, “top executives have already gone through the process and recommend that their direct subordinates experience it” (Interviewee 1). Interviewee 20 also stated that “the president and directors recommend the coaches they already know, when they appreciate their work and want their teams to go through the process.” In addition, since it is a large financial investment, it is most widely used by large companies, which have resources for this type of training, unlike small or medium-sized firms or local organizations that give priority to technical training. In any case, respondents’ perception is that, even in the case of HR professionals who are familiar with the process, “genuine attention is fresh, and only in recent years they have gone through training in coaching, in order to know its benefits and applications” (Interviewee 8).

The common perception is that professionals who work at HR departments have not evolved as much as business media show, and they lack greater knowledge about the coaching practice. This was confirmed by the results of a survey (Coutu et al., 2009), where 29.5 percent of coaching relationships were initiated by the HR department, 28.8 percent by the executives themselves, 23 percent by their heads and 18.7 percent by others. The fact that the process is recommended by other professionals may be beneficial, on the one hand, to demonstrate its acceptance by top management; but, on the other, it shows that the initiative does not come (mainly) from HR professionals, which can mean that they do not fully master it.

Among the respondents’ comments, some believe that HR professionals also hire coaches “as a way to show they are up-to-date with the latest developments in people management, and also to expand their network of contacts to outside consultants” (Interviewee 14). Given the uncertainties of the market, “partnerships can be useful, even for acting as a coach in the market” (Interviewee 14).

The organization’s demand for concrete results, when the coach is an outside consultant, “is still not entirely clear and, although there are goals for the coach and the coachee, most of the time they are not measurable” (Interviewee 8). The more structured the company, the greater the tendency to pre-determine results. Some respondents said that the coaches themselves must address this issue “when the company doesn’t give enough emphasis, and it is a way of ensuring the credibility of coaching, since HR departments are often not ready for that” (Interviewee 10). Such unpreparedness shows that the expression “strategic HR” is not appropriate in practice (Brewster, 2007; Wood et al., 2011).

4.1.3. Analysis of the Portuguese context for the use of coaching

In Portugal, the impact of the recent crisis is evident, and many organizations have reduced their investments in training. There was a change in the demand for coaching services, especially since 2014, and companies had to compete and re-evaluate the market, which was “previously more guaranteed” (Interviewee 1). It was necessary to review and negotiate prices, compared to the former abundance of resources and the easy acceptance of the original budgets proposed by coaches. HR departments were forced to “do more with less, and this had a direct impact on coaching services in companies” (Interviewee 2). What some of the respondents say, like Interviewee 15, is that “despite an increase in the demand for coaching, there are many suppliers in the market, which led to different forms of negotiation.”

From a contextual view, the use of coaching increased over the past ten years, but has gained more relevance in the last five years (Dominguez, 2016). “The media and the growth in the number of qualification programs, together with much advertising, contributed to the expansion” (Interviewee 3). “On the one hand, this supports its greater diffusion” (Interviewee 3), “but on the other hand there is a risk of distorting the essence of coaching, leading to confusion on its real nature and application, which is not good for the serious professional” (Interviewee 1). The view of those who have done this for a longer time is more critical, since “there is a high risk of trivialization” (Interviewee 15).

Regarding the reasons for its use, until five years ago companies tended to hire a coaching process almost exclusively to improve the performance of their executives (Barosa-Pereira, 2008), by understanding that this was “the last chance for a professional who was not “performing well”; that is, coaching was seen as a miracle” (Interviewee 8). In recent years, this perspective was expanded (João, 2017), with coaching being used for other needs, such as to achieve more assertive professional attitudes and actions to improve the relationship between leader and team. Likewise, the target audience of the process increased, with current demands for specific actions toward “young talents that the company is afraid of losing. In Portugal, as salaries are lower than in the rest of Europe, it is common for them to receive generous offers and leave the companies” (Interviewee 9).

Other audiences begin to emerge, “from young people in search of support for career issues, to people with retirement prospects” (Interviewee 4). In these cases, the demand is individual and does not originate in organizations. Interviewee 11 also highlights that the number of professionals from startups has grown. This shows how “younger individuals are an audience that values the search for self-knowledge in order to seek new professional routes, since they are entrepreneurs and do not want to submit to market rules.”

4.1.4. Use of coaching in organizations

The use of coaching discloses implementation problems but also benefits, and, above all, it emphasizes ambivalences (Joo, 2005; Nieminen et al., 2013). Among the greatest difficulties is “the diversity of suppliers in the market, which confuses the hiring organization” (Interviewee 5). Organizations often hire based on recommendations from other companies, and this helps them to know the potential results and benefits (Underhill et al., 2010). Although these references are important, “caution is necessary, because organizational contexts and cultures are distinct, openness to the process is different in each firm, and these variables change the results, possibly by frustrating expectations” (Interviewee 7).

In addition, there is often the case where companies “hire coaching, but do not make changes in their daily practices and leadership attitudes” (Interviewee 9). Thus, how can you have a “coaching attitude that questions and seeks feedback in a company where criticizing leadership is a taboo? This is inconsistent!” (Interviewee 10). Professionals who undergo a coaching process often experience these paradoxes, and it is a “concern for coaches who want to help companies move forward” (Interviewee 10). Hence, coaches need to work not only with the coachee, but “extend their conversations, including guidance to HR professionals and managers, and make sure that the debate reaches others involved with the issue” (Interviewee 12).

As Interviewee 1 states, “I almost never come across organizations that have a “coaching culture,” that carry out their processes for HR, recruiting, hiring, evaluating potential, training or giving feedback with a coaching attitude.” It is noteworthy that the expression “coaching culture” is not frequent in the literature (Hwang & Rauen, 2015), but, according to some of the respondents (especially Interviewees 14 and 18), it refers to the concern for having a culture of dialogue, partnership and collaboration in the companies.

Among the benefits of the process, emphasis on its differentials stands out, compared to other modalities of people development, since “it allows a deeper and lasting change, with the definition of actions and their follow-up, thus ensuring its difference from training, where the participant, after leaving, forgets what was learned, does not practice it, and nobody asks questions” (Interviewee 9).

The practice of coaching, “in itself, reinforces the idea that participants receive special attention from the organization” (Interviewee 19), which will lead to a greater investment in their growth. Thus, coaching takes place as a kind of “customized development, at each professional’s pace, according to his/her possibilities and limitations” (Interviewee 7). Such elements strengthen the arguments of Barosa-Pereira (2008) and Resende (2016).

4.1.5. Education and certification process

There is a consensus that it is “fundamental to ensure good education as a coach in accredited education institutions” (Interviewee 8). This is why there is a set of associations and certifiers that operate to ensure qualification criteria and updated knowledge and experience (Coelho, 2016), “limiting the spaces of practice for bad coaches and preventing professionals trained over a weekend from being called coaches, even without the capabilities required” (Interviewee 3).

Regarding the education and certification of coaches and the criteria for hiring them by organizations, “the actions of the associations and the certifications have been a differential, because they help to separate the good ones from the bad ones” (Interviewee 10). More structured HR departments are beginning to require coaches to present their certifications by accredited associations, as a way to guarantee credibility and quality.

There is another issue that was not anticipated in the interviews’ script, related to how organizations hire coaches. The most common case is large organizations contracting big consulting firms that have coaching as one of their areas of expertise. Thus, they are protected from hiring potential “fakes” (Interviewee 6); that is, the “name of a major consulting firm ensures that the coach is certified, besides establishing a formal channel between the client organization and the coach” (Interviewee 6). In this case, the coach usually does not work alone, but in projects of larger groups. There are also situations in which “the company hires through large consulting firms, but requests that one or more specific coaches be included in the group of professionals, because it already knows them and wants their services, even if they are independent. In any case, the coach is usually certified and therefore more respected. To be certified is always a differential!” (Interviewee 7).

Therefore, certification should also be object of caution (Ferreira, 2008), since there are education institutions that are also certifiers, which generates mistrust. As Interviewee 2 comments, “I qualify and also certify, and this does not seem appropriate; there should be another authority to check the quality of education and ensure the necessary impartiality for providing a certification.”

4.1.6. Human resource professionals – coaches

There are different opinions regarding the internal HR professional acting as a coach at the company. On the one hand, there are respondents who consider that this action brings benefits, since it can help to expand the audience assisted by coaching. Being an expensive process for the company, it is often exclusive for the executive level. In this case, the introduction of the coaching process by HR professionals could be beneficial. On the other hand, most believe that there is a conflict of interest, and that HR professionals would hardly work with the top executives of the company, because they would not feel comfortable to talk about subjects that are more personal.

The issue of confidentiality is also a problem for this practice, which strengthens the arguments of Battley (2006). The main issue would be the natural obstacle for coachees to expose themselves to someone who works in their organization and has the “duty” to pass on information to the owners and/or to their superiors.

In any case, respondents observed that education in coaching for HR professionals “is useful for their work, and would lead to a change in attitude, by improving the contracting of outside services; that is, they would not work as a coach, but with the style of a coach” (Interviewee 5).

The interviewees’ speech shows that there is a significant concern about the image of companies’ HR departments. In the end, “if there is so much discussion on this point, and a perceived lack of credibility of HR professionals, it is because this category has not been able to define its role in the companies, regarding the employees, and this is worrying” (Interviewee 1). In addition, a matter came up in some interviews. It refers to “a certain difficulty for HR professionals to deal with a greater empowerment of the leadership, provided by coaching, which would mean, in turn, a loss of their power. While, at the same time, they argue that leaders must lead their teams, they do not facilitate their development and keep on nurturing their dependency on the HR department” (Interviewee 10).

This reinforces one of the fundamental pillars of coaching, which regards the reliability of the conversations between coach and coachee (Batista & Cançado, 2017; Pliopas, 2014; Campos & Pinto, 2012), and can lead to discomfort for the organization. By funding this activity, the company thinks that it will have full access to information about each individual. According to Pliopas (2014, p. 24), “it is important that the manager, together with the HR professional and the employee, explains to the coach what kind of development to expect. This is usually done in a meeting between the client and his/her manager, in the presence of a HR professional, where the coach facilitates this interaction.”

4.1.7. The role of the leader-coach

The education of leaders to act as leader-coaches, as well as the perceptions about HR professionals acting as coaches, is object of different opinions. On one side, there are respondents who believe that leaders should play this role, because every leader should be the main coach in his/her organization. On the other side, some disagree and think that leaders may have the attributes of a coach, but since they need to be directive and guide the way forward, this position would be inconsistent with a coaching role. In general, there is a consensus that leaders should undergo “not only formation, but experience the process, because this would make them adopt an attitude of coaches” (Interviewee 7).

This would imply acting in a more participative and provocative way, and to mobilize the potential of the people they lead, rather than taking an authoritarian position. It also assumes a greater concern for the development of these people, making them evaluate alternatives and reflect on their positions, at all times. The differences of opinion also reflect the distinct approaches on this topic, such as those by Campos and Pinto (2012), Goldsmith et al. (2012) and Graziano et al. (2014).

4.1.8. The future of the coaching process

Regarding the future of coaching, which involves controversies in the process, challenges for its establishment, and perceived risks and opportunities, there is one common issue in the respondents’ statements: the coaching process is directed to an elite in organizations, usually top managers and outstanding professionals (the “talents”) that the organization hopes to keep, because they are valuable to the business. In order to expand its use, we expect that, in the near future, leaders will be multipliers of a “coaching culture” in companies. To do this, they will need the support of HR departments, which would require a strategic attitude of the area, “still not clearly perceived in most companies” (Interviewee 1).

There are others who mention that the process “should be internalized in the companies, as happened with other management technologies, such as feedback, previously an exclusive knowledge of consulting firms, that was incorporated after the internal training of professionals” (Interviewee 8).

In addition, the prospect of greater expansion of the target audience has been under discussion, through accessible virtual tools (such as Skype), or through the use of technological resources for questionnaires (such as Survey Monkey) that may be self-applied, with on-demand coaching interventions to facilitate the aspects that need improvement. These last two issues were discussed at the International Columbia Coaching Conference (2016).

Among the risks, “the excessive proliferation of training programs, without the necessary quality for a complete formation” (Interviewee 9) worries respondents, who fear their indiscriminate multiplication, harming the professionals who do a good work. This reinforces one of the most often mentioned topics regarding the future, which is the “professionalization of the coaching process, which will ensure recognition of the activity” (Interviewee 16).

Respondents are unanimous to state that coaching can be a way of improving working conditions and also life, by increasing self-knowledge and knowledge of others, in the same organization, as well as benefits in social interactions, in general (Rocha-Pinto & Snaiderman, 2014).

5.Final remarks

At a time when coaching is increasingly adopted by companies, literature review mentions few academic studies on the process, from the perspective of coaches, and involving the participation of HR professionals and departments. This shows the need to expand academic research on this subject.

This paper sought to fill this gap by reflecting, analyzing and opening up new possibilities for research on the practice of coaching, and examined its controversial and critical points, from the perspective of 20 experts and coaches.

The results show that there is unanimity in some issues, and disagreement in others. Convergence refers especially to the benefits of the process for organizations and professionals, both in terms of the training experience and the implementation. They also agree that HR professionals need to be better prepared for hiring coaches, and this leads to the need for their own education in this area. However, there are differences and some prudence regarding HR professionals and company leaders that take on the role of coaches in their organizations.

The choice of a qualitative approach for the research brought new findings, through the expansion of the scope to address little explored contents, which were not planned initially. This was the case of the discussion about coaching, not as an intervention tool but as a process that uses other tools for its application. This idea strengthens the notion of an organizational management concept based on “coaching culture,” that is, with the perspective of policies and practices for people management that involve greater openness to feedback, participation in decision-making and analysis of employees’ potential, instead of the traditional performance evaluations.

Coaching would be, in this sense, a practice inspired by collaboration, by openness to listen to people and treat them in a more humanized way. However, as used today, in an elitist way and directed toward a few members of the top hierarchical level of companies, it seems a limited process, with a result below its possibilities, either in terms of a “coaching culture” for organizations, or as an individual and professional development process. In its turn, HR departments do not show signs of enhancement, at the pace demanded by the changes in the global labor market.

Among the implications of this study, the emphasis on the need for a greater discussion about the subject, either through the increase of scientific investigations, or the inclusion of this topic in spaces of knowledge, as universities and professional associations of coaching and HR. In addition, the development of public policies that include coaching processes in entities that deal with the labor market, in order to develop citizens with a greater career autonomy.

When analyzing participants’ statements, it is clear that coaching is still a different practice in the market, subject to controversies that range from its overvaluation as a miraculous process, capable of reversing bad performances, to criticisms of being just another management fad, and a product for commercial sale with an excess of suppliers and no quality criteria.

The main objective of the paper was to carry out an analysis of the coaching process, its convergences and discrepancies, from the perspective of experts and professionals. Our conclusion is that there is still a long path to cover in academic studies on this subject. There were many divergences regarding the categories and dimensions surveyed (Table II), which are object of discussion both in the labor market and the academic world. This reinforces the need for institutionalization of this activity, regulation of the profession and a greater focus on its quest to become a field of knowledge with its own characteristics, although built on a diverse range of contributions from other areas. Thus, there is a favorable perspective of evolution, since the results of this study also point to some convergences. Regarding the actions of professionals and HR areas in adopting the coaching process, the expected achievement of more strategic results linked to business are still not fully understood. HR areas continue to react to market changes without concern for following and checking the coaching process and its impacts on organizational performance. These departments and their professionals focus on the immediacy of personal changes in individuals that undergo this process (coachees), instead of looking at the global performance of the organization. Thus, they keep a shortsighted view of their role in the companies.

The objective dealt with the shortage of scientific references to support the practical actions of the coaching process in the labor market, in order to present and explain the controversies about its use and the stigma of being a fad, but we observed few advances. There are many non-scientific manuals and articles about the coaching process that disseminate content that was not checked and confirmed. Therefore, there is a lack of consistent information for professionals, organizations and society about the real possibilities and results that should be expected from a coaching action. Hence, it is necessary to increase scientific research to balance and compensate for media news.

The results show benefits and limitations of the coaching process. The former are personal and professional benefits for the coachee, such as increased job satisfaction, greater capacity for leadership and enhanced performance. As for the organization, improved professional and leadership performance, greater job satisfaction and a better ambiance, increased credibility regarding its investments, with the retention of key professionals; and for society, the possibility to rely on leaderships able to provide more humanized organizational environments and improve their performance, which will lead to success in the market and increased competitiveness. These development actions of professionals have an impact on other people, inside and outside the organizational context. Regarding the main limitations, the coaching process still does not have tools to measure its results, it is not seen as an integrated action of people management in companies, but as occasional interventions on some key professionals, and there is a great deal of misinformation in the market, caused by the trivialization of its use.

Finally, we can conclude that there is an effective belief in the potential and benefits of coaching, on the part of experts and coaches, and a necessary link between this process and human resource management.

It is important to define a research agenda that will shed light on the process, such as extending this study toward a comparative analysis of the academic literature with the practice of coaching in Brazil, as well as investigating other audiences, especially from the perspective of HR professionals and coachees.

References

1. Amorim, W. A. C. (2015). Negociações coletivas no Brasil: 50 anos de aprendizagem. Atlas: São Paulo.

2. Andrade, L. (2016). O que é o coaching e o que não é. In A. Vinagre, H. Anjos, M. João, M. J. Martins, & R. G. Loureiro (Eds.), International coach federation [ICF] – chapter Portugal, Coaching 10 anos: ir mais longe cá dentro (pp. 19–31). Lisboa: Lousanense.

3. Araújo, A. (2010). Coach: um parceiro para o seu sucesso. São Paulo: Gente.

4. Bardin, L. (2011). Análise de conteúdo (p. 70). Lisboa: Edições.

5. Barosa-Pereira, A. (2008). Coaching em Portugal: teoria e prática. Lisboa: Sílabo.

6. Batista, K., & Cançado, V. L. (2017). Competências requeridas para a atuação em coaching: a percepção de profissionais coaches no Brasil. REGE – Revista de Gestão, 24(1), 24–34.

7. Battley, S. (2006). Coached to lead: how to achieve extraordinary results with an executive coach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

8. Bauer, M. W., & Gaskel, G. (2002). Pesquisa qualitativa com texto, imagem e som: um manual prático. Petrópolis: Vozes.

9. Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling: problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research, 10(2), 141–163.

10. Boxall, P., & Purcell, J. (2011). Strategic and human resource management. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

11. Brewster, C. (2007). Comparative HRM: European views and perspectives. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(5), 769–787.

12. Brewster, C., Mayrhofer, W., & Reichel, A. (2011). Riding the tiger? Going along with Cranet for two decades: a relational perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 21(1), 5–15.

13. Campos, T. M., & Pinto, H. M. N. (2012). Coaching nas organizações: Uma revisão bibliográfica. REUNA, 17(2), 15–26.

14. Cavanagh, M., Grant, A. M., & Kemp, T. (Eds.) (2005). Evidence Based Coaching. Vol. 1 – Theory, Research, and Practice from the Behavioural Sciences. Bowen Hills: Australian Academic Press

15. Coelho, A. P. (2016). Acreditação de programas coaching. In A. Vinagre, H. Anjos, M. João, M. J. Martins, & R. G. Loureiro (Eds.), International Coach Federation [ICF] – Chapter Portugal, Coaching 10 anos: ir mais longe cá dentro (pp. 91–100). Lisboa: Lousanense.

16. Coutu, D., Kauffman, C., Charan, R., Peterson, D. B., Maccoby, M., & Scoular, P. A. (2009). What can coaches do for you? Harvard Business Review, 87(1), 91–97.

17. Creswell, J. W. (1997). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. London: Sage.

18. Delbridge, R., Hauptmeier, M., & Sengupta, S. (2011). Beyond the enterprise: broadening the horizons of International HRM. Human Relations, 64(4), 483–505.

19. Diedrich, R. (2001). Lessons learned in – and guidelines for – coaching executives teams. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 53(4), 238–239.

20. DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160

21. Dominguez, A. (2016). A evolução do coaching em Portugal nos últimos dez anos. In A. Vinagre, H. Anjos, M. João, M. J. Martins, & R. G. Loureiro (Eds.), International Coach Federation [ICF], Chapter Portugal, Coaching 10 anos: Ir mais longe cá dentro (pp. 239–246). Lisboa: Lousanense.

22. Ferreira, M. A. A. (2008). Coaching: Estudo exploratório sobre percepção dos envolvidos – organização, execução e coach. Dissertação de Mestrado, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade, São Paulo, SP: Universidade de São Paulo.

23. Fischer, A. L. (2001). O conceito de modelo de gestão de pessoas – modismo e realidade em gestão de Recursos Humanos nas empresas brasileiras. In J. S. Dutra (Ed.), Gestão por competências: um modelo avançado para o gerenciamento de pessoas (pp. 9–22). São Paulo: Gente.

24. Fischer, A. L., & Albuquerque, L. G. (2005). Trends of the human resources management model in Brazilian companies: a forecast according to opinion leaders from the area. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(7), 1211–1227.

25. Goldsmith, M., Lyons, L. S., & McArthur, S. (2012). Coaching: o exercício da liderança. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier.

26. Grant, A., & Cavanagh, M. (2004). Toward a profession of coaching: sixty-five years of progress and challenges for the future. International Journal of Evidence-Based Coaching and Mentoring, 2(1), 1–16.

27. Graziano, G. O., Peixoto, C. A., Pizzinatto, A. K., & Castro, D. S. P. (2014). Coaching e mentoring como instrumento de foco no cliente interno: Estudo regional em SP. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(1), 47–59.

28. Guerra, I. C. (2006). Pesquisa qualitativa e análise de conteúdo: sentidos e formas de uso. Lisboa: Principia.

29. Hodge, J. (2016). A morphological and bibliological analysis of the international journal of evidence based coaching and mentoring 2003-2012. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 14(1), 86–107.

30. Hwang, J. M., & Rauen, P. (2015). What are Best Practices for Preparing High-Potentials for Future Leadership Roles? New York, NY: Cornell University, ILR School.

31. Instituto Nacional de Estatística (2017). Boletim Mensal de Estatística 2016. Lisboa: INE/PORDATA.

32. International Coach Federation [ICF], Chapter Portugal (2016). Coaching 10 anos: Ir mais longe cá dentro. Lisboa: Lousanense.

33. International Columbia Coaching Conference (2016). The Future of Coaching. New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University. Available from: https://convention2.allacademic.com/one/ccc/ccc16/

34. João, M. (2017). Coaching. Lisboa: Lua de Papel Editora.

35. Johnson, L. K. (2007). Getting more from executive coaching. Harvard Management Update, 12(1), 3–6.

36. Joo, B. K. B. (2005). Executive coaching: a conceptual framework from an integrative review of practice and research. Human Resources Development Review, 4(4), 462–488.

37. Kampa-Kokesch, S., & Anderson, M. Z. (2001). Executive coaching: comprehensive review of the literature. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 53(4), 205–228.

38. Kets De Vries, M. F. (2005). Leadership group coaching in action: the Zen of creating high performance teams. Academy of Management Executive, 19(1), 61–76.

39. Lages, A., & O’Connor, J. (2010). Como funciona o coaching: o guia essencial para a história e a prática do coaching eficaz. Rio de Janeiro: Qualitymark.

40. Lange, A., & Karawejczyk, T. (2014). Coaching no processo de desenvolvimento individual e organizacional. Diálogo, (25), 39–56.

41. Latham, G. P., & Stuart, H. C. (2007). Practicing what we preach: the practical significance of theories underlying HRM interventions for a MBA school. Human Resource Management Review, 17(2), 107–116.

42. Laville, C., & Dionne, J. (1999). A construção do saber: manual de metodologia da pesquisa em ciências humanas. Porto Alegre: Artmed.

43. Legge, K. (2006). Human resource management. In S. Ackroyd, R. Batt, P. Thompson, & P. S. Tolbert (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of work and organization (pp. 220–241). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

44. Matos, J. N., & Domingos, N. (2014). Novos Proletários: a precariedade entre a ‘classe média’ em Portugal. Lisboa: Edições 70/ Le Monde Diplomatique.

45. Melo, L. H., Bastos, A. T., & Bizarria, F. P. A. (2015). Coaching como processo inovador de desenvolvimento de pessoas nas organizações. Revista Capital Científico – Eletrônica (RCCe), 13(2), 141–153.

46. Micklethwait, J., & Wooldridge, A. (1998). Os bruxos da Administração: como entender a babel dos gurus empresariais. Rio de Janeiro: Campus.

47. Milaré, S. A., & Yoshida, E. M. P. (2007). Coaching de executivos: adaptação e estágio de mudanças. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 9(1), 86–99.

48. Minayo, M. C. S. (2001). Pesquisa social: Teoria, método e criatividade. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes.

49. Nieminen, L., Smerek, R., Kotrba, L., & Denison, D. (2013). What does an executive coaching intervention add beyond facilitated multisource feedback? Effects on leader self-ratings and perceived effectiveness. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 24(2), 145–176.

50. Orenstein, R. L. (2002). Executive coaching: it’s not just about the executive. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 38(3), 355–374.

51. Parente, C. C. R. (1996). As empresas como espaço de formação. Sociologia, Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, (6), 89–150, Available from: http://ler.letras.up.pt/uploads/ficheiros/1394.pdf

52. Pliopas, A. L. V. (2014). Coaching: modo de usar. GV-Executivo, 13(2), 22–25.

53. Resende, P. (2016). Estrutura do processo de coaching. In A. Vinagre, H. Anjos, M. João, M. J. Martins, & R. G. Loureiro (Eds.), International Coach Federation [ICF], Chapter Portugal, Coaching 10 anos: ir mais longe cá dentro (pp. 73–80). Lisboa: Lousanense.

54. Rocha-Pinto, S. R., & Snaiderman, B. (2014). Coaching executivo: a percepção dos executivos sobre o aprendizado individual. Gestão & Planejamento, 15(3), 553–573.

55. Rodrigues, C. F., Figueiras, R., & Junqueira, V. (2016). Desigualdade do rendimento e pobreza em Portugal: as consequências sociais do programa de ajustamento. Lisboa: Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos.

56. Schuller, R. (1992). Strategic human resources management: linking the people with the strategic needs of the business. Organizational Dynamics, 21(1), 18–32.

57. Souza, C. C. S. (1979). Afinal, a administração de recursos humanos é uma função realmente estratégica? Revista de Administração Pública, 13(3), 69–83.

58. Souza, M. M., Calbino, D. P., & Carrieri, A. P. (2010). Dos recursos humanos à gestão de pessoas: Reflexões arqueológicas das mudanças conceituais. Gestão & Planejamento, 11(1), 104–118.

59. Ulrich, D., Ypunger, J., & Brockbank, W. (2008). The twenty-first-century HR organization. Human Resource Management, 42(4), 829–850.

60. Underhill, B. O., McAnally, K., & Koriath, J. J. (2010). Coaching executivo para resultados: guia definitivo para líderes organizacionais. Osasco: Novo Século.

61. Whitmore, J. (2010). Coaching para performance: aprimorando pessoas, desempenho e resultados. Competências pessoais e profissionais. Rio de Janeiro: Qualitymark.

62. Witherspoon, R., & White, R. P. (2001). Executive coaching: a continuum of roles. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 48(2), 124–133.

63. Wood, T. Jr, & Paula, A. P. P. (2006). A mídia especializada e a cultura do management. Organizações & Sociedade, 13(38), 91–105.

64. Wood, T. Jr, Tonelli, M. J., & Cooke, B. (2011). Colonização e neocolonização da gestão de recursos humanos no Brasil (1950-2010). Revista de Administração de Empresas, 51(3), 232–243.