Dossiê

An autobiographical history of Ethno Sweden

An autobiographical history of Ethno Sweden

Revista Orfeu, vol. 4, no. 2, 2019

Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina

Received: 27 June 2019

Accepted: 14 December 2019

Abstract: Ethno is a multicultural summer camp for young musicians interested in traditional, folk and world music which began in Sweden in 1990 and continues today, having spread over 15 countries in the last decade. It is characterized by its peer-to-peer learning approach whereby young people teach each other the music from their countries and cultures. This article reconstructs part of the history of Ethno Sweden through an autobiographical report written by its founder, Magnus Bäckström, about the origin, ideology, strategies, and organization of the event. Interviews with the current organizer, Peter Ahlbom, complement this report detailing the organization of the event after Magnus’ departure, the process of its affiliation to the non-governmental organization Jeunesses Musicales International, and its expansion to other countries. Information is given about how the organization of Ethno Sweden went from the Falun Folkmusic Festival to Rikskonserter (Concerts Sweden) and then to Folkmusikens Hus in Rätvik.

Keywords: Ethno, Sweden, Summer camp, Folk Music, Traditional Music, World Music.

Resumo: Ethno é um acampamento de verão multicultural para jovens músicos interessados em música tradicional, folclórica e mundial que começou na Suécia em 1990 e continua até hoje, tendo se espalhado por 15 países na última década. Caracteriza-se por sua abordagem de aprendizagem ponto a ponto, na qual os jovens ensinam uns aos outros a música de seus países e culturas. Este artigo reconstrói parte da história da Ethno Suécia por meio de um relatório autobiográfico escrito por seu fundador, Magnus Bäckström, sua origem, ideologia, estratégias e organização do evento. Entrevistas com o atual organizador, Peter Ahlbom, complementam este relatório detalhando a organização do evento após a saída de Magnus, o processo de afiliação à organização não governamental Jeunesses Musicales International e sua expansão para outros países. São fornecidas informações sobre como a organização da Ethno Suécia foi do Festival Folkmusic da cidade de Falun para Rikskonserter (Concertos na Suécia) depois para Folkmusikens Hus, na cidade de Rätvik.

Palavras-chave: Ethno, Música Floclórica, Música Tradicional, Música do Mundo.

1. Introduction

Ethno is a musical summer camp for young musicians interested in folk, world, and traditional music. It was founded in Sweden in 1990 and still happens every year, and has spread through over 15 countries. As its website highlights,

At the core of Ethno is its democratic peer-to-peer learning approach whereby young people teach each other the music from their countries and cultures. It is a non-formal pedagogy that has been developed over the past 25 years and embraces the principals of intercultural dialogue and understanding. The goal is that through these interactions, musicians will be inspired to deepen their musical interests and build a global network to support their future careers. Each Ethno event embraces a combination of workshops, jam sessions, seminars, and performances to develop young musicians both personally and technically. (Ethno)

While writing about Ethno Sweden after having participated in 2018, I, Hugo Ribeiro, realized that even though almost 30 years had passed since its first occurance, there had been no published texts about it that could retell its origin, inspiration, and the intentions that served as a guide to structuring its organization.

Having conducted a personal interview during the event in 2018 with Peter Ahlbom4, the head organizer of the event, and some subsequent email exchanges with him, some questions remained unanswered, because Peter’s involvement with this project started in 1994 and he was not involved in its creation. By his guidance and intermediation, I was able to get in touch directly with Magnus Bäckström, who conceived of and produced this project in the early years.

This text is therefore based on the article written by Magnus Bäckström himself, and the interviews performed with both Magnus and Peter. The primary purpose here is to fill in some gaps about this project so that future researchers, when writing about their experiences with Ethno, can get firsthand information to understand how this idea came into being.

This text is divided into five sections. 1) An introduction to explain the context and reasons behind publishing this autobiographical report; 2) A curriculum vitae of Magnus Bäckström; 3) The story Magnus wrote based on questions I posed (Magnus’ own words); 4) Some information given by Peter Ahlbom that may fill in Magnus’ report (Peter’s own words); 5) Conclusion, where I try to summarize all the information along with my recent experience with Ethno.

I blended this report with an interview I did with Bäckström by email to clear up some doubts. All my insertions are in italic. My name is marked beforehand, to clarify which are my words and which are Bäckström’s. I also included some footnotes to provide the names of institutions, people, projects, and so on. Thus aside from Magnus’ report written by him, and Peter’s reply (also written by himself), all other texts are my responsibility.

2. About Magnus Bäckström

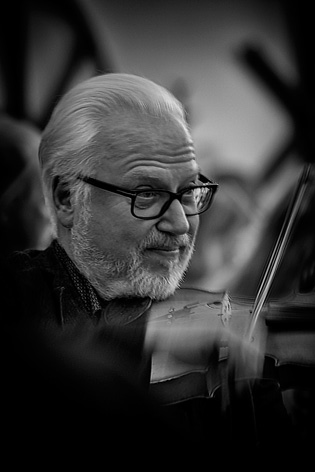

Magnus Bäckström was born 1954 in the village Furudal in the region of Dalarna, Sweden, an area well known for its influential traditional culture. He started to play the folk fiddle at the age of 16 and took part in the vivid 70s revival of folk and traditional music in Sweden. Magnus was a semi-professional folk musician in the 1970s and 80s performing, touring and recording. He traveled all over Sweden and was part of several handpicked groups to represent Swedish folk music at festivals and concerts in Finland, Norway, Denmark, UK, USA, Holland, Switzerland, and Japan. Bäckström appears on some 20 recordings, some of them considered milestones in the development of Swedish traditional music. He is the composer of Ungerska Järnvägen, a tune included in the standard repertoire by folk musicians all over Sweden5.

Working as a part-time music teacher in the elementary school parallel to his own touring and performing during this period, he also held numerous evening classes, weekend and week-long courses in folk fiddle. He is the author of two tutorials, one for the vallhorn, a Swedish herding instrument made of cow or goat horn, and one for the Swedish folk flute spilåpipa. For some years he worked as a music consultant within the voluntary educational system in Sweden.

In 1976, Magnus and his friend and music partner, Per Gudmundson, founded the legendary Swedish folk music record company Giga. He is also the founder and former director of Falun Folkmusic Festival, one of the world’s largest folk/world music festivals in the 1980s and 90s, and founder and former director of internationally-spread folk/world music youth camp Ethno. He is also founder and former director of leading Swedish folk/world/jazz music magazine Lira, founding member and former vice chairman of the network organization Sweden Festivals, founding member and former chairman of the network organization European Forum of Worldwide Music Festivals and artistic director of the world music expo Womex 98.

Magnus Bäckström was the first CEO and artistic director of Gävle Concert Hall, inaugurated in 1998, and the first CEO and artistic director of Uppsala Concert and Congress Hall opened in 2007. From 2014 to 2018, he was the director of Kultur i Väst, the regional cultural development institution in the west part of Sweden.

After receiving several local, regional and national music and culture awards, he is retired since 2018, but is still active as a musician on a non-professional level, and as a board member of various organizations and institutions.

3. Magnus Bäckström’s report about Ethno

Dear Hugo,

I appreciate your interest in Ethno. This project makes me very happy and proud. I wish I was 20 years old again and could be an active part of this fantastic journey. Now I follow the development of Ethno through websites, social media, and YouTube. Moreover, now and then through encounters with participants, leaders, and researchers like yourself. Again, Ethno makes me very happy.

I will try to help you in your efforts. I feel that I need to give a proper background.

Ethno is based on strong beliefs and ideology. It had/has a purpose and was/is part of a broader social strategy. The first Ethno was thoroughly planned. Maybe you will get too much material, and perhaps I am too ambitious. However, I think this background is vital for you in your work regarding Ethno.

3.1 Folk music movement in the 1970s

The origin of Ethno camps should be seen in a specific context. Let us go back 20 years before Ethno started. In 1970 I began to play fiddle and Swedish folk music. Many of us, younger folk musicians, were part of the alternative music movement in Sweden. We took a stand against the ruling cultural norm. We did not like the national romantic, folklore spirit that folk music took in the decades before us. We felt it was false, nationalistic, and conservative. We looked for older and more “original” folk music, rougher and not so refined, and we also worked on rebirth for some forgotten old folk instruments.

Playing folk music was for us not only for fun; it was also an attitude and a statement. It meant a particular cultural approach and specific cultural values. We valued the idea of nurturing many voices (music, styles, genres), all equal in value, and we were against what we called cultural imperialism.

This situation did not happen only in Sweden. You find this happening at the same time all over the western world. It could turn out in different ways in different countries, but it had the same roots – from Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger to the wave of British folk-rock, the revival of Cajun music in Louisiana, the rebirth of Rebetica in Greece, of the Swedish polskas, and the Hungarian village czardas in the dance houses of Budapest.

The movement was international, and so were we. We felt a relationship to other folk or traditional musicians all over the world. We played different styles, different instruments, but we were colleagues and equals.

3.2 The struggle for acknowledgment

Soon we found out that the music genres that we represented were not part of the popular song structures in Sweden. It was the case of folk music in many countries for that matter. Swedish folk music was respected and valued in many music circles, yes, but the genre was not part of the structures and systems. Folk music was considered amateur music.

Sweden has a fantastic music education system for children and youngsters, but at that time you could only learn western classical music there, not folk music. The same thing with higher music education – only western classical music, and maybe some jazz. No folk music. Folk musicians performed at folkloristic events at outdoor museums and alike, not at the prestigious music venues.

To us, this indicated that the society did not value this music “for real.” So – we had to do something about it! We had to work in various ways to get folk music more acknowledged and a natural and equal part of the musical landscape in the society.

Most important to achieve this was, of course, to play good music. However, apart from that, we worked to develop a professionalization within this genre, and infrastructure for this music. Parallel to this, we worked on opinion making and lobbying in various ways.

So, many of us became entrepreneurs and cultural activists. Many small record companies were started7, lots of educational activity started. You could see an increasing number of events. We became concert promoters, organizers and presenters, researchers. We worked with media, instrument building, among other things.

This cultural context around folk music in Sweden became effervescent, lots of ideas arose, and some turned into reality. Ethno was, and hopefully is, part of all this and those efforts.

3.3 Ethno roots

As told before, I started to play the fiddle in the 1970s. In the late 70’s I became a part-time professional folk musician with national and international tours, recordings, radio broadcasting, appearance in TV shows. I was also teaching folk music in evening classes, weekends, and summer camps. I wrote a couple of tutorials about Swedish herding instruments (the cow or goat horn “vallhorn” and the shepherd’s flute, “spilåpipa”). My friend and music partner, Per Gudmundson (now head of Folkmusikens Hus in Rättvik), and I started the record label Giga8. During ten years, we produced several LPs and cassettes, many of them groundbreaking or avant-garde in the spirit mentioned above.

In 1986 I started Falun Folkmusic Festival (FFF) together with some of my friends, many of them folk fiddlers9. FFF was one of the significant folk or world music events in the world in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s.

With the festival as a platform we, on my initiative, developed other activities related to folk or world music: Ethno; a yearly market place and business meeting for Nordic folk/world music called Norrsken; higher music education (university level); and Lira, a regular professional magazine for folk and world music10.

Hugo Ribeiro: What was Norrsken?

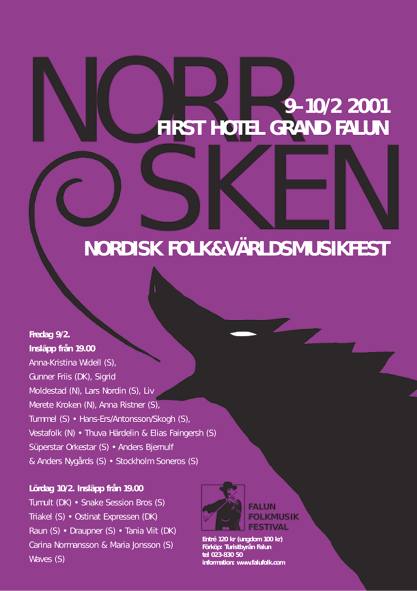

Norrsken was (it does not exist any longer) the yearly business meeting for Nordic folk/world music. It was a market place for Nordic folk/world music similar to Womex, (World Music Expo), Folk Alliance, and others. A few hundred folk/world professionals or semi-professionals in the Nordic countries (artists, agencies, record companies, institutions, organizations, promoters, festivals, media) gathered at the Grand Hotel in Falun for 3-4 days of seminars, showcases, expo, and networking. I could not find any info online. There were some articles from Swedish folk-music-organization-magazine-member Spelmannen about the first editions in 1996 and 1997 and a poster from 2001 edition (Fig. 1).

Hugo Ribeiro: How were those initiatives related to higher music education? What did you do or plan to do? At which university? What happened?

We launched two courses: Folkmusik i Norden (Folk music in the Nordic countries) and Folkmusik i Världen (Folk music around the globe). They were part of Högskolan i Falun/Borlänge (now Högskolan Dalarna) which is university level. They were for one year, organized as not full-time studies but 50%, meaning that after one year you got university points as if you had studied full time half a year.

Students came from all over Sweden and got together in Falun on many weekends during the year. In between these weekends they studied and worked individually.

The new thing about these two courses was that they were based on playing the music yourself (not only have seminars, lectures, and listen to recordings). For example, when the theme was Balkan music, you of course read and had theoretical talks about Balkan music but, most importantly, you played music from the Balkans, which gave you a deeper understanding and relation to the music.

Headteacher of Folkmusik i Norden was Mr. Sven Ahlbäck, and head teacher of Folkmusik i Världen was Mr. Owe Ronström. Both were and are musicians, and also ethnomusicologists (both are now professors).

The university courses in Falun had been held a few years ago (I do not remember how long). It was the embryo of the courses Sven Ahlbäck11 then started at the Royal Academy of Music in Stockholm, where he still works.

So, the general approach or strategy, for me, was to fill in the gaps. What was missing in the infrastructure? What was needed? There was no tutorial for spilåpipa, so I made one. No record label presented this specific artist or style, so Per Gudmundsson and I started a label. There was no big festival that presented top creative quality folk/ethnic/world music from all over the world, so I started one, and so on.

3.4 How Ethno started

The first Ethno was in 1990, but the story begins a couple of years earlier, in 1987 or 1988. I was at a music conference somewhere in Sweden. Part of the program was regular presentations and updates of various activities from representatives of music institutions and others in Sweden. One of the performances was by Mr. Gunnar Nolgård who worked at Rikskonserter, Swedish Concert Institute12. Rikskonserter was the Swedish partner of Jeunesses Musicales13 (JN), and Gunnar Nolgård was head of Musik för Ungdom (JM Sweden).

I had worked together with Rikskonserter since the ‘70s and knew many of the people there very well. I knew Gunnar from before, and I knew about JM. Gunnar made a presentation of the JM flagship World Youth Orchestra (WYO), its background, and it is purpose14. He talked about the peace dimension and the general inspiration in bringing young musicians from different countries together, but also that the WYO project helped to build contacts, an international network, for future professional life and career. He also presented, at that time, the quite newly developed World Youth Choir15 (WYC) with the same ambitions and goals as for WYO.

I had heard his presentation before, but this time, I started to react and think. Society, the established music environment, provides and is funding serious and substantial music projects like this within western classical music, but what about folk music? Shouldn’t there be the same opportunities for young folk musicians?

So there was a gap to be filled, and perspectives to be challenged!

3.5 Ethno – the goals

I started to think about how one should/could organize a similar project as WYO and WYC but for young folk musicians from all over the world. The goals should be the same: peace, inspiration, and building an international network. However, folk/world music adds two more dimensions: 1) the variety of music styles brings a more comprehensive musical reference to the individual, which also can be substantial creative and artistic input, and 2) you get encouraged and strengthened coming from a small, often marginalized, music tradition at home into a global context where you and your music are appreciated and highly valued.

However, which format? WYO and WYC are ensembles, but creating a group would be against the nature of these genres and should not be the objective. The goals are described above, and the answer was not to create a big ensemble with a mix of instruments, sounds, and genres from all over the world. Various temporary ensembles would still develop when playing together during an Ethno camp, just because it is nice to play along. It would happen regardless, and this is part of the Ethno recipe. However, it is not the goal.

The important thing was to create a platform, an opportunity to meet and to play. The rest would come naturally. A fixed result is not the goal. The “being” is the thing. It is a simple recipe: put 100 young musicians together one week. We all know what will happen. Just keep trust in the power of the music itself, and the rest will come. The challenge is to keep that trust and stay calm.

Hugo Ribeiro: Where did the name “Ethno” come from?

We needed a name that was easy to work with, and that indicated what it was. “Folk,” “Trad,” was not so accurate. “World music” was not established at that time and would also have been strange and unfamiliar. The Falun Folkmusic Festival programming committee discussed the project and the name, and committee member Tomas Fahlander suggested the name Ethno. Gunnar Nolgård and I then decided to name the project Ethno.

Hugo Ribeiro: Were there others involved in this initial creative process?

Not really. My experience from the festival project was to work thoroughly with the idea before you present it to others, and I did the same with Ethno. So most of the content and concepts were mine. Then I offered a synopsis to others, including Rikskonserter/JM Sweden. Moreover, of course, others had input. But mainly, it was my thinking.

3.6 Still, a structure is needed

Hugo Ribeiro: Where did the idea of involving artistic leaders to help the young musicians come from? Was it always that way since the first year? Why did you let the young musicians become the ones to teach the music instead of experienced teachers? What if they were shy or lacked pedagogical training?

It was from the beginning. It was quite common for us to organize week-long summer courses or weekend courses, and this was something similar, though the leaders were not supposed to teach but to support and coach the young musicians. Having experienced teachers instead would make the camp “just another music camp.” When you train yourself, you are the one who represents your tradition, your music. Hopefully, it gives you a boost. If they are shy they should not be forced, I think. If they lack pedagogy, well, that is why coaching and support are there.

So the workshop structure was what I decided. You “teach” or share a moment of your music with the others, and you get a glimpse of their music in return. No one becomes an expert, but you get a glimpse of something new. New musical landscapes are opened, and you have the opportunity to go further if you want.

So workshops where youngsters taught each other were the foundation (See Fig. 2). Apart from that, there was an emphasis on social activities (dancing, excursions, parties, swimming) and on some concerts. Concerts were part of the program mostly because it is something you expect to do as a musician. I am sure that many young musicians would have been disappointed if there were no concerts for them. So we planned a few smaller public shows during the Ethno week and, of course, a final concert.

The public concerts were also a way to promote the Ethno camp, to let the public and the cultural institutions, media, know about it. It was, however, essential to keep the number of concerts at a manageable level so that they did not interfere with the core ambitions of Ethno. The challenge, in the beginning, was to keep the structure seriously informal, to give “enough” structure to give some order but still allowing creative encounters to happen. Losing this might easily create, again, “just another music camp” in the western tradition. It is difficult to describe, but in my opinion, may be one of the essential things about Ethno.

Hugo Ribeiro: Why one week? Why not two weeks or three days?

Time is needed to establish and develop both relations and music. Less than one week would be too short for that, and two weeks can be challenging in regards to costs, being away from home too long.

3.7 Which year?

I had the idea already a couple of years before the first Ethno 1990. I used my experience from planning and launching Falun Folkmusic Festival, which I did three years in advance, and decided to plan at least two years also for Ethno. 1990 had been declared the “Year of Folk music and dance” in Sweden, and I was involved as vice chairman in the national committee for that project. The thematic year provided an excellent opportunity to launch the first Ethno.

3.8 Which period?

Falun Folkmusic Festival started in 1986 and was held from Wednesday until Saturday, in mid-July, every year. The festival presented concerts, of course, but also many week-long courses in various music and dance styles. The classes with some 600 participants started on Sunday a couple of days before the concerts.

The festival Musik vid Siljan was arranged the week before in Rättvik and Leksand, close to Falun. This festival presented many folk music activities, including the famous folk music event Bingsjöstämman (Fig. 5 and 6. Compare them to see how similar the ceremony still looks like, even after almost 30 years). The initial idea was to arrange Ethno in Falun the week before Falun Folkmusic Festival, and parallel to Musik vid Siljan. This would provide opportunities for the Ethno participants to take part in Musik vid Siljan activities and to be free to join the activities during Falun Folkmusic Festival (Ethno participants were invited to stay for the festival and were offered free lodging and free access to many events).

So Ethno 90 and Ethno 91 were arranged Sunday-Sunday the week before Falun Folkmusic Festival, but from 1992 Ethno was arranged Wednesday-Wednesday, starting some days before the festival courses started and then running parallel with the courses.

3.9 The strategy

I have mentioned that Ethno also was/is part of a plan. Ethno is art, but it is also cultural politics. One of my strategic goals was to get Jeunesses Musicales International “in the boat.” I wanted Ethno to be the folk/trad answer to WYO and WYC and to be positioned on the same level as these two projects. That was important to me and reflected the general strategy that was the ideological platform for all my work.

Therefore, I approached Gunnar Nolgård (Rikskonserter / JM Sweden) in the fall of 1988 and presented the idea to him. He liked the idea and decided that JM Sweden (Musik för Ungdom) should become a partner. He agreed that we should work to try to get JMI involved, but he also foresaw some difficulties for that to happen.

We decided to start Ethno and approach JMI with a long-term perspective. Therefore, we also planned some extra activities for the first Ethno to get tools to promote the project. We hired a film crew to make a short presentation VHS filmed at Ethno 9016, and we hired a photographer to get professional photographs – all of this to promote Ethno mainly to JMI. It was also vital for me to involve the Swedish folk music organization Sveriges Spelmäns Riksförbund17, and hopefully also other Nordic folk music organizations. The reason was, of course, that this would give engagement and “legality” within the genre, and also to widen the perspectives and references for all involved. One must remember that the general view, and especially regarding nonwestern cultures, was not something that was on the agenda in these organizations at that time. Rikskonserter/JM Sweden and the folk music organizations were not in as funding partners but could provide production support and contacts and, moreover, “legality.”

3.10 The organization

Falun Folkmusic Festival, an independent foundation of which I was the founder and the director, was the main organizer for Ethno. We had a year-round office with a staff that was working with this kind of music every day, and that had an international network already. The festival organized some 40 week-long courses with 600 participants yearly, so we were used to working with applications, information, lodging, meals, transports, volunteers, finances, administration. We could use the festival’s marketing channels also for Ethno, and we could use the festival itself as an extra value to Ethno participants (they were welcome to stay a few additional days for the festival.)

Being the director of the festival, I was also the director of Ethno, and the FFF staff worked all year planning Ethno. FFF staff member Margareta Heijkenskjöld was a crucial person in the Ethno organization throughout the years. Gunnar Nolgård and his colleague at that time, Monica Lindqvist, were working with some of the Ethno planning from their office at Rikskonserter in Stockholm. During Ethno, Gunnar and his staff also were on the spot in Falun and worked at the Ethno/FFF office. Gunnar Nolgård retired in 1992, and Monica Lindqvist replaced him. Kajsa Paulsson was part of the Rikskonserter staff at Ethno from 1992 and some years on. After some years, Anette Liljefors at Rikskonserter substituted Monica Lindqvist working with Ethno.

Amongst other things, Rikskonserter helped with Ethno’s graphic design and logo. The role of JM Sweden developed to focus on one or two more difficult Ethno projects yearly, to raise funds for and organize participants from developing countries in Asia or Africa.

FIJM/JMI together with ICTM (International Council for Traditional Music) supported Ethno with funding 1991-1993, but it took many years before Ethno became a formal JMI project. I was the director of FFF and Ethno until 1997, and Ethno becoming an official JMI project did not happen for my years.

Sveriges Spelmäns Riksförbund, the Swedish folk musicians’ organization, was also a partner for many years. Their office was in Falun, next door to the festival office, and the director Kalle Rapp worked with Swedish Ethno participants together with the regional organizations. He also worked with the other Nordic folk music organizations who also were involved as partners.

So, from 1990 to 1997, Ethno was organized by Falun Folkmusic Festival in cooperation with Svenska Rikskonserter/JM Sweden, Sveriges Spelmäns Riksförbund and the Nordic folk music organizations.

The first Ethno, 1990, had 120 participants from 15 to 25 years old. They came from Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the United Kingdom (Shetland Isles). The Nordic profile was not chosen and invitations were sent out all over the world, but the result was not so surprising for the first year.

I was leading the Ethno project all year. The weeks before the days during and after the festival were jam-packed so I had to find another person to be the artistic director for the Ethno week and to be the leader of the camp. The administration and the logistics were taken care of by our and Rikskonserter’s staff, Kalle Rapp and others. We needed an Ethno director/headmaster/artistic director for the camp. It was essential to choose someone who understood and was able to carry the specific artistic idea and attitude that was so important to me. It was imperative, especially in the first years, until it had settled.

I asked Mr. Lars Lundgren (Fig. 11), a Swedish fiddler, to be the first Ethno director, and together, we picked out the other leaders. The leaders should have a varied (folk) musical background and should work mainly as support and coach. We had already a strong network of suitable musicians. Ethno had excellent leaders that stayed with the project for several years. Lars Lundgren was the director/headmaster in 1990 and 1991. From 1992 another fiddler, Mr. Anders Bjernulf, took over the leadership for some years.

One cannot overestimate how important those first years were to establish a particular Ethno spirit and attitude. Everyone involved was crucial!

3.11 Ethno and JMI

Some months after the first Ethno, in October 1990, Gunnar Nolgård and I traveled to Jeunesses Musicales general assembly in Brussels to promote Ethno as a JMI project. We had a small exhibition in the foyer and also made a presentation to the delegates.

There was some interest amongst individuals but not particularly from the organization in general. At that time JMI was still very much focused on western classical music, and a project like Ethno was maybe too strange. JMI was just not ready. However, JMI decided to support Ethno financially from 1991-1993.

Gunnar and others continued to lobby for Ethno at JMI in the coming years, and eventually, it happened. Ethno became a JMI project! But that happened long after I left in 1997.

3.12 Ethno after 1997

I created and organized Ethno from scratch (1987-1989) with eight events in a row (1990-1997). The work started in 1987 or 1988, so it was ten years of Ethno for me. I do not know when it changed to Rikskonserter. [Actually, Folkmusikens Hus holds the rights to organize it.]. Falun Folk Music Festival closed in 2004. It became smaller and smaller and also changed profile gradually. I cannot say how this affected Ethno since I was not involved in the festival or Ethno at that time.

Hugo Ribeiro: Do you believe the idea of Ethno is still the same or has something changed?

I have the impression that it still is more or less the same idea. I also get the feeling that a kind of community has developed amongst Ethno goers, and that many people are “ethnonians” that travel from camp to camp, from country to country. That is nice of course, but if Ethno becomes a more or less closed community from that, a clan or a sect, then the beautiful Ethno project has become something that works in the opposite direction from the original ideas and values. A right balance is critical.

You find the original purpose and goals in the text I wrote: peace, inspiration, building international network, broader musical reference, creative and artistic input, self-esteem, and encouragement. I have the feeling that Ethno has meant very much to many young musicians, both artistically and personally. In Sweden, where Ethno has existed for almost 30 years, we have whole generations of musicians that are former Ethno goers. I do not think you can find any of the profiled younger folk musicians in Sweden that have not been to Ethno at least once, and many have been several times. That has, of course, influenced the whole genre. Within Swedish folk music today you find an openness to and interest in other music cultures that is unique, and makes Swedish folk music perhaps the most dynamic and progressive genre in Sweden!

Hugo Ribeiro: What about the future?

Maybe I will start a Senior Ethno for older youngsters 50+. That would be something, wouldn’t it!?

4. Peter Ahlbom’s reply (in his words)

The Falun Folkmusic Festival was in charge of Ethno from the beginning of 1990 to 2006. When Magnus Bäckström left FFF in 1997, the festival general after him was Hans Hjorth. As the FFF closed in 2006, Ethno moved to Rattvik in 2007.

Rikskonserter/Concerts Sweden was a governmental organization that organized tours with foreign musicians in Sweden (jazz, folk and classical music), and also promoted Swedish music in those genres abroad. Over the years, Ethno became more and more run by Rikskonserter, and Music for Youth/Musik för ungdom became the Department for Children and Youth at Rikskonserter and also the Swedish section of JMI. Rikskonserter took over most of the financing and the work with Ethno. Employee Margareta Heijkensköld helped with recruiting participants and paperwork, while Rikskonserter paid for Ethno, organized leaders, travel, posters, and the website.

In 2011 Rikskonserter was officially terminated. In that year, Folkmusikens Hus took over as the sole organizer of Ethno, since they had been in partnership with Rikskonserter since 2007. From 2008 until now, 2019, Karin Hjertzell, an employee from Folkmusikens Hus, has been responsible for the organization of Ethno.

My first Ethno was in 1994. That year we had 105 participants. A few years later, a decision was made to limit the number of participants to 100. More than that was considered too many for practical reasons. The workshops were pretty much the same the first years as they are today, but the awareness of all kinds of social issues areas is much bigger today, I think. Ethno as a peace project was there from the start, but because of the growing nationalist parties with xenophobic programs, the refugee situation, etc., there is a more significant focus on those issues today. Equality and gender issues are also subjects that have surfaced over the years.

During the festival years, Ethno had one big concert at the festival but also a few small gigs at hospitals and nursing homes. Participants were also experiencing the festival on their own, of course.

The age range was 15-25 years in the beginning, but we raised that once we noticed that some 15-year-old Swedes were too young to hang out with 25-year-old adults from all over the world. So now we have 17-25.

Hugo Ribeiro: Why do you think that one of the strategic points for Magnus was to have the Ethno camp as a JMI project?

The reason Magnus had this goal was that Rikskonserter/Music for Youth was the Swedish section of Jeunesses Musicales International. In those days JMI was uninterested in any music besides classical music. So one of his goals was to make JMI see the quality in folk music and after that, start working with folk music. He was (like many others in Sweden) upset because the World Youth Orchestra and World Youth Choir received such significant financial support from JMI and folk music got zero.

When he ran Ethno through his festival from 1990-97, there was only one Ethno in the world. Ethno was not a project within JMI – that happened many years after that. Also, for many years, it was just a small part of JMI and not very important. In 2000 JM Sweden organized the JMI General Assembly in Mora and that year we took all the delegates to an Ethno workshop. It might have been the first time the JMI delegates were introduced to the project at all.

JMI started getting interested in Ethno probably around 2004 or so, when Matt Clark18 and I started working with the organization. So when JMI wanted to present Ethno as a JMI program, some people (including me) were a bit irritated. “Do they want to steal our project?” But since more Ethnos had been started, we could see the importance to have a hub like JMI for all of us.

There are still some organizations that run Ethno camps without being part of JMI: Ethno in Chile for example and some smaller Ethno-like projects. You cannot forbid them to do that, but the Ethno Committee (representatives from all Ethno organizations in JMI) wants everyone to join the organization, of course. I am not sure if JMI owns the right to the name “Ethno.” I am not sure it is registered in Belgium. If someone starts an Ethno camp and calls it Ethno without being a member, they will be contacted and asked to join the organization. But you cannot force them, I think. Ethno Sweden has the name “Ethno” registered in Sweden, so no one can call a project Ethno here without talking to us first.

For some small Ethnos without support from organizations, it costs a lot to be a member of JMI, even though the fee they pay is considered low by the staff and more prominent organizations. Moreover, many ask themselves, “what is in it for me?” It is a difficult task for JMI to show them why it is a good idea to be a partner.

I think there are good reasons why Ethno should have an international “host” like JMI. They organize the network. They have the website; they have a tool kit for new Ethnos, they can help with graphic design; they can sometimes sponsor meetings, and can assist in finding new contacts in new countries. But all of us want to keep our freedom too. We all run our Ethnos’ in our way, even though we have the basic educational idea in common.

Hugo Ribeiro: I believe we talked about a course in France to help people who want to act as young leaders in Ethno?

“Ethnofonik” is the name of the leader training in France. There is absolutely no rule that says you have to go that course to work as a leader! You can hire whomever you want. But the course is suitable for young people who want to learn more about pedagogy, the peer-to-peer learning process, to get a network of other leaders, so we support that, and we want to bring in young leaders who have attended that course. But it is not necessary—people can have other experiences from similar music camps that are perfectly OK.

5. Conclusion

As is possible to see from Magnus’s and Peter’s testimony, Ethno Sweden went through some turbulent circumstances, but it managed to keep going all those years. After M. Bäckström left, the administration of Ethno Sweden was shared between the Falu Folkmusic Festival and JM Sweden, where JM Sweden provided the main funding. When FFF finally closed down in 2006, JM Sweden/Concerts became the main responsible organization, and also the core funder of the project. At the same time it moved the activities to Rättvik, where the collaboration with the Folkmusikens Hus started. It was also from that time on that Ethno became more firmly established as a JMI program. Only when Concerts Sweden closed down in 2011 were the rights and responsibilities of Ethno Sweden transferred fully to Folkmusikens Hus, under the responsibility of Karin Hjertzell, who happens to be Peter Ahlbom’s wife.

In the year 2019 it celebrates 30 years with its 30th festival, witnessing how far it has come and spread throughout the world, and ramified into other projects inspired by its philosophy. The history of Ethno in Estonia is an example:

ETHNO camps have been regularly held in Estonia since 1997. At that time, two traditional music students, Krista Sildoja and Tuulikki Bartosik, had the chance to participate at the ETHNO camp in Falun, Sweden. This experience gave them a desire to do something similar in Estonia as well. The first traditional music camp inspired by their ETHNO experience, took place in the same year in Viljandi, right before the Viljandi Folk Music Festival, where the youngsters ended the camp with a big concert. Since 2000, it has been called ETHNO Estonia. (Viljandi folk music festival)

Two years later, in 1999, it was Belgium19 that began to organize an Ethno camp. Since then, Ethno has been held in more than 20 countries as diverse as India, Uganda, Palestine, New Zealand, and Brazil20. Another branch is Ethno on the road, the tour version, that has been running annually for 16 years. The website explains:

As always Ethno Sweden selects a band to tour in Sweden in the autumn. Five participants plus two experienced Ethno leaders get together to spread some joy and great Ethno music to the Swedish public for two great weeks together. This year the tour will start with a gig at the Folkmusiknatta festival in Falun on November 10 and end with another fantastic concert at the World music festival in Piteå up in the far north of Sweden. (Folkmusikens Hus)

Even if JMI delayed its total embrace of the Ethno project, it is now one of JMI’s main projects, acting as “JMI’s global program for folk, world and traditional music” (Jeunesses Musicales International), organizing courses for anyone who wants to be an artistic leader in camps around the world, and selling this philosophy of music experience exchange.

The latest news is recent funding from a philanthropic institution in the USA that will benefit hundreds of musicians with scholarships to attend various Ethnos around the world, and fund a 3-year research project that “will focus on the impact that Ethno has had on the lives of young musicians, personally and professionally”.21 Also, a researcher from Brazil, Antenor Correa, has attended Ethno Sweden for the last three years in order to experience its pedagogy to apply it in more formal situations, like classes in university level degree music courses. This will probably result in even more articles and possibly even theses and dissertations focusing on the musical and human connection we experience when attending an Ethno camp as the research of Roosioja (2018).

Clearly, this text brings just a part of Ethno’s history. A JMI official account is missing (not contacted for this interview), a collection of the stories behind each camp around the world, and a study focused on its peer learning pedagogy and the important role of artistic leaders. So there remain some gaps to fill.

References

Ethno. Info. Disponível em www.ethno-world.org/info/, acessado em 18 out 2018.

Folkmusikens Hus. Ethno on the road!. Available at http://ethno.se/ethno-onthe-road/?lang=en, accessed April 12, 2019.

Jeunesses Musicales International. Our story. Available at http://jmi.net/about/ our-story, accessed Nov 18, 2018.

Roosioja, Lisandra. 2018. “An ethnographic exploration of the phenomenon behind the international success of Ethno”. Master’s Thesis. Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre.

Viljandi folk music festival. What is Ethno?. Available at https://www.viljandifolk. ee/festival/get-involved/estonian-ethno, accessed April 12, 2019.

Wikipedia contributors. Jeunesses Musicales International. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jeunesses_Musicales_International&oldid=833015292, accessed Nov 18, 2018.

Notes